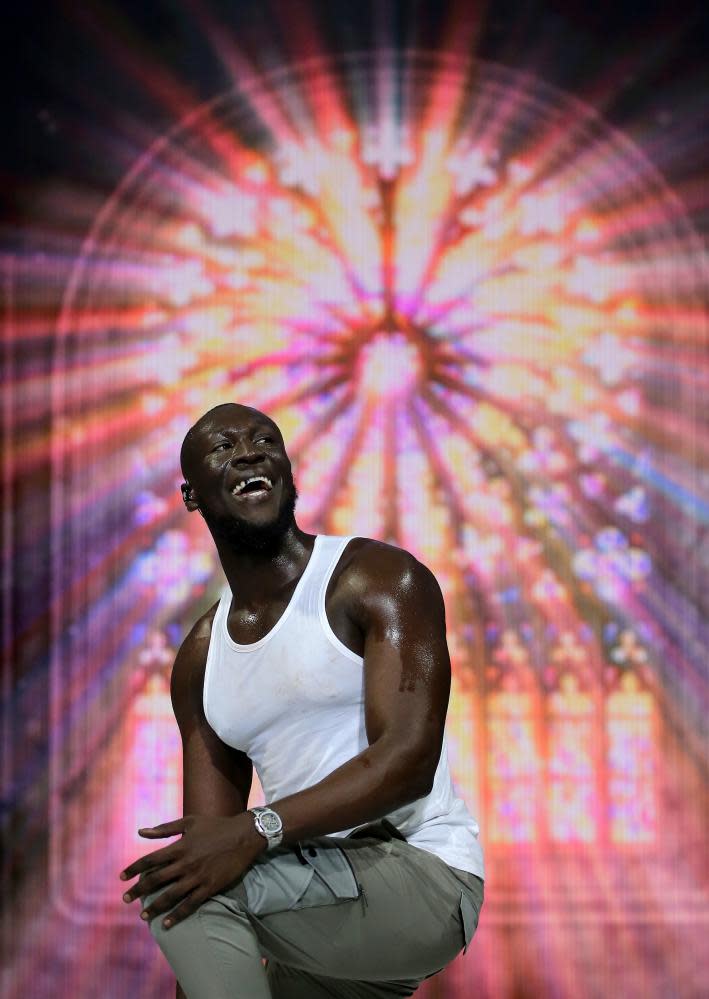

Stormzy: Heavy Is the Head review – a hyper-confident return

“How’s the best spitter in grime so commercial?” wonders Stormzy on Wiley Flow, a standout track off his second studio album, Heavy Is the Head. It is a pointed rhetorical flourish from a man who mostly wears the mantle of street poet-king like a tracksuit made of fine silk.

It was, arguably, only a matter of time before grime threw up its true crossover star. That the genre should have found one as analytical, mould-breaking and assured as Stormzy is a particular thrill. His second album continues seamlessly on from 2017’s landmark No 1 Gang Signs & Prayer. If anything, Heavy Is the Head grandstands harder, sings more sweetly and examines the rapper’s own conscience even more attentively than before.

First and foremost, this is a hyper-confident return – top-heavy on front, stats and burns. Joining Wiley Flow and Vossi Bop – two of four strong pre-album tracks – are just shy of half a dozen more cocky tracks, all of which re-establish Stormzy’s verbal pre-eminence with panache. Rather than building a career purely from party rap, songs for “the ladies” or postcode beef, Stormzy has risen largely through the old-school medium of witty bragging – a combination of menace and humour that remains on point here. He does a fine line in pique, his brow furrowed in aggrieved disbelief. “Ah man, the audacity!” he actually growls on the standout Audacity, taking on unnamed pretenders (“ashy youths”) and false friends (“wolves in sheepskin”).

Performance statistics abound on Stormzy’s battle raps, as he tots up venue capacities around the country, or boasts about chart positions and units sold – somewhere between a company CEO, Jay Z (his declared role model) and a directeur sportif. Of course, Michael Ebenazer Kwadjo Omari Owuo Jr is “young, black, fly and handsome” too (Handsome), as photogenic on the cover of GQ as he is on the cover of Time magazine, being profiled as a Next Generation Leader. On the unapologetic Pop Boy, Stormzy notes that he has become a London “top boy” without actually having to become a gangland supremo.

That top boy reference now works internationally too, thanks to the recent Netflix reboot of the Channel 4 crime saga of that name. If Gang Signs & Prayer enabled Stormzy to headline Glastonbury, Heavy Is the Head makes a bid for Stateside attention too: never before has UK hip-hop had such traction there.

The spaciousness, punch and depth of these productions is telling, but it is a mark of the album’s artistic integrity that Stormzy manages to transcend genre (again) without sacrificing his core griminess, or losing too much in the way of accent, word choice, content or theme. There are no obvious North American rapper hook-ups; the Hand of Drake is absent.

HER is one well-chosen US guest vocalist on One Second, an emotive plea to take time and calculate one’s wellbeing, just as Afrobeats superstar Burna Boy is an apposite, timely guest on Own It – this album’s sole, sultry come-hither.

The brassy fanfares that open and close Big Michael, though, are played by London jazz players. Grime’s favourite insult – “suck your mum” – recurs a handful of times, and the busily polyrhythmic Superheroes works as an extended shout out to black British talent, name-checking Malorie Blackman and Dave.

But pugnacious localism is only part of Stormzy’s appeal. Heavy Is the Head once again highlights the personal downsides of recognition. Weariness is nothing new in hip-hop – rappers have been counting the cost of being the boss for decades. Gang Signs & Prayer, too, made it clear that Michael Omari felt ambivalent about the noblesse oblige of starriness.

Stormzy, though, manages to keep this tired trope fresh. His regrets are legion: the friends for whom he was not there, the street pain from which he is now just a little removed, “the little things”.

“They’re sayin’ I’m the voice of young black youth, I say ‘yeah, cool’ and bun my zoot,” he eye-rolls on Crown. While many artists spark up as an act of hedonism or rebellion, Stormzy often smokes his weed in an act of self-medication. There are repeated pleas throughout the album for self-care – to take time out, to remember to breathe, not to let one’s dreams disrupt one’s sleep too much. Exasperation at being misunderstood or misrepresented is never far away, though. “I’m not the poster boy for mental health!” Stormzy exclaims at one point. Another track seethes at the flak Stormzy received for starting a Cambridge scholarship for BAME students (“it’s not anti-white it’s pro-black,” he points out).

For all that Stormzy is well able to carry the weight of representing not just south London, British blackness and now the UK creative industries as well, his game does drop sharply on one key track. It is tempting to hear Lessons as an extended apology to Stormzy’s ex, the broadcaster Maya Jama – the two split up earlier this year amid rumours of his infidelity. (That narrative seems borne out by lines like “You gave me the world and I gave you disrespect”.) But Stormzy can only muster sentimental prose here, rather than memorable poetry – a common problem when aggressive rhymers find themselves out of water, floundering in their “feels”. Still: we sorely need better flows about love, not strings of cliches.

Bum notes are relatively few, however. The 50-odd minutes of Heavy Is the Head passes in a blur of street status and lyrical power, tempered by nuanced considerations of sacrifice. One reason the crown feels so heavy on Stormzy’s head is that he is acutely aware of the shoulders on which he stands, of the timing that is one aspect to his success. So many previous MCs enjoyed chart heat without becoming national treasures. Dizzee Rascal, Wiley, Lethal Bizzle, Skepta and Kano have all made bids for the crown at one time or another, all too often with the club-grime hybrids that marked the decade where MCs could not perform live due to the Metropolitan police’s notorious, now defunct Form 696 policy.

Ours is an often bewildering era, but that grime is now an export, and that Stormzy is the country’s unofficial poet laureate, is a particularly shiny silver lining.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News