The story behind Bonfire Night and Guy Fawkes: Gunpowder, treason and plot

It's nearly that time of year again - when we Britons gather in parks and gardens to watch dummies burn on bonfires and fireworks light up the sky, wrapped up in woolly hats and gloves.

The jovial atmosphere is a far cry from the origins of November 5, which are shrouded in religious tension and a foiled assassination attempt.

November 5 is a date when Britons commemorate events that nearly changed the course of the nation's history. But what actually happened that night, and what part did Guy Fawkes play?

The Gunpowder Plot

November 5 commemorates the failure of the November 1605 Gunpowder Plot by a gang of Roman Catholic activists led by Warwickshire-born Robert Catesby.

When Protestant King James I acceded to the throne, English Catholics had hoped that the persecution they had felt for over 45 years under Queen Elizabeth I would finally end, and they would be granted the freedom to practice their religion.

When this didn't transpire, a group of conspirators resolved to assassinate the King and his ministers by blowing up the Palace of Westminster during the state opening of Parliament.

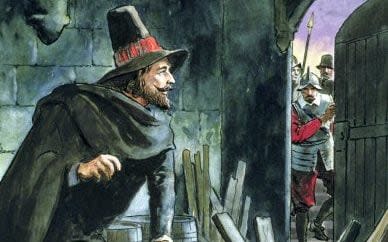

Guy (Guido) Fawkes, from York, and his fellow conspirators, having rented out a house close to the Houses of Parliament, managed to smuggle 36 barrels of gunpowder into a cellar of the House of Lords - enough to completely destroy the building.

(Physicists from the Institute of Physics later calculated that the 2,500kg of gunpowder beneath Parliament would have obliterated an area 500 metres from the centre of the explosion).

The scheme began to unravel when an anonymous letter was sent to William Parker, the 4th Baron Monteagle, warning him to avoid the House of Lords.

The letter (which could well have been sent by Lord Monteagle's brother-in-law Francis Tresham), was made public and this led to a search of Westminster Palace in the early hours of November 5.

Explosive expert Fawkes, who had been left in the cellars to set off the fuse, was caught when a group of guards discovered him at the last moment.

Fawkes was arrested, sent to the Tower of London and tortured until he gave up the names of his fellow plotters.

Lord Monteagle was rewarded with £500 plus £200 worth of lands for his service in protecting the crown.

Guy Fawkes' co-conspirators

Guy Fawkes, Thomas Bates, Robert and Thomas Wintour, Thomas Percy, Christopher and John Wright, Francis Tresham, Everard Digby, Ambrose Rookwood, Robert Keyes, Hugh Owen, John Grant and the man who organised the whole plot - Robert Catesby.

The conspirators were all either killed resisting capture or - like Fawkes - tried, convicted, and executed.

The traditional death for traitors in 17th-century England was to be hanged, drawn and quartered in public. But this proved not to be the 35-year-old Fawkes' fate.

As he awaited his punishment on the gallows, Fawkes leapt off the platform to avoid having his testicles cut off, his stomach opened and his guts spilled out before his eyes.

Mercifully for him, he died from a broken neck but his body was subsequently quartered, and his remains were sent to "the four corners of the kingdom" as a warning to others.

The aftermath

Following the failed plot, Parliament declared November 5th a national day of thanksgiving, and the first celebration of it took place in 1606.

King James I also sought to control non-conforming English Catholics in England. In May 1606, Parliament passed 'The Popish Recusants Act' which required any citizen to take an oath of allegiance denying the Pope's authority over the king.

Observance of the 5th November Act, passed within months of the plot, made church attendance compulsory on that day and by the late 17th Century, the day had gained a reputation for riotousness and disorder and anti-Catholicism. William of Orange's birthday (November 4th) was also conveniently close.

Remember, remember...

The actions of Guy Fawkes are immortalised in the nursery rhyme 'Remember, remember'. Although several different versions exist, the first five lines remain to same in all.

Remember, remember, the fifth of November Gunpowder treason and plot

We see no reason

Why Gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot ….

Guy Fawkes, guy, t'was his intent

To blow up king and parliament.

Three score barrels were laid below

To prove old England's overthrow.

By god's mercy he was catch'd

With a darkened lantern and burning match.

So, holler boys, holler boys,

Let the bells ring.

Holler boys, holler boys,

God save the king.

And what shall we do with him?

Burn him!

Another version, which is said to have been penned around 1870, displays - or perhaps parodies - anti-Catholic sentiment which is said to have risen following the passing of the 5th November Act.

A rope, a rope, to hang the Pope,

A penn'orth of cheese to choke him,

A pint of beer to wash it down,

And a jolly good fire to burn him.

Guy Fawkes Day today

The Houses of Parliament are still searched by the Yeomen of the Guard before the state opening. The idea is to ensure no modern-day Guy Fawkes is hiding in the cellars with a bomb, although it is more ceremonial than serious. And they do it with lanterns.

The cellar that Fawkes tried to blow up no longer exists. In 1834 it was destroyed in a fire which devastated the medieval Houses of Parliament. The lantern Guy Fawkes carried in 1605 is in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

Bonfire night traditions

Guy Fawkes Day is celebrated in the United Kingdom, and in a number of countries that were formerly part of the British Empire, with fireworks, bonfires and parades. Straw dummies representing Fawkes are tossed on the bonfire, as well as those of contemporary political figures.

Dummies have been burned on bonfires since as long ago as the 13th century, initially to drive away evil spirits. Following the Gunpowder Plot, the focus of the sacrifices switched to Guy Fawkes' treason.

Traditionally, these effigies called 'guys', are carried through the streets in the days leading up to Guy Fawkes Day and children ask passers-by for "a penny for the guy." Today the word 'guy' is a synonym for 'a man' but originally it was a term for a "repulsive, ugly person" in reference to Fawkes.

The fireworks represent the explosives that were never used by the plotters.

In Ottery St Mary, south Devon, in a tradition dating from the 17th century, barrels soaked in tar are set alight and carried aloft through parts of the town by residents. Only Ottregians - those born in the town, or who have lived there for most of their lives - may carry a barrel.

Lewes, in southeastern England, is also the site of annual celebration. Guy Fawkes Day there has a distinctly local flavour, involving six bonfire societies whose memberships are grounded in family history stretching back for generations.

The only place in the UK that does not celebrate Guy Fawkes Night is his former school St. Peter’s in York. They refuse to burn a guy out of respect for one of their own.

The origins: fireworks and bonfires

During the 10th century a Chinese cook discovered how to make explosive black powder when he accidentally mixed three kitchen ingredients – potassium nitrate or saltpetre (a salt substitute used in the curing of meat), sulphur and charcoal.

The cook noticed that if the concoction was burned when enclosed in the hollow of a bamboo shoot, there was a tremendous explosion.

Fireworks arrived in Europe in the 14th century and were first produced by the Italians. The first recorded display was in Florence and the first recorded fireworks in England were at the wedding of King Henry VII in 1486.

The word ‘bonfire’ is said to derive from 'bone-fire', from a time when the corpses of witches, heretics and other nonconformists were burned on a pyre instead of being buried in consecrated ground.

Fireworks should be enjoyed at a safe distance and adults should deal with firework displays and the lighting of fireworks. They should also take care of the safe disposal of fireworks once they have been used.

Here are the 10 firework rules to follow

Plan your firework display to make it safe and enjoyable.

Keep fireworks in a closed box and use them one at a time.

Read and follow the instructions on each firework using a torch if necessary.

Light the firework at arm's length with a taper and stand well back.

Keep naked flames, including cigarettes, away from fireworks.

Never return to a firework once it has been lit.

Don't put fireworks in pockets and never throw them.

Direct any rocket fireworks well away from spectators.

Never use paraffin or petrol on a bonfire.

Make sure that the fire is out and surroundings are made safe before leaving.

'Anonymous' protests

November 5th has become an important date globally now that political activists all over the world are wearing Guy Fawkes masks to protect their identity. These masks were inspired by Alan Moore's dystopian 'V for Vendetta', the 1988 graphic novel whose main character is loosely based on Guy Fawkes.

In recent years, supporters of anti-Capitalist group Anonymous have taken to the streets in cities and towns worldwide in the so-called 'Million Mask March' against political oppression.

Traditional Bonfire Night food

The traditional cake eaten on Bonfire Night is Parkin Cake, a sticky cake containing a mix of oatmeal, treacle, syrup and ginger.

Proper parkin is a dark, sticky cake-cum-flapjack, not just a gingerbread. It’s good warm with custard as a pudding, perhaps with some poached pears, too.

4 1/2oz /125g butter

4oz/110g caster sugar

5oz/ 140g black treacle

4oz/ 110g golden syrup

8oz/225g medium oatmeal or porridge oats blended in a food processor to a coarse sandy consistency

4oz/ 110g self-raising flour

3 tsp ground ginger

1 tsp ground mixed spice

Pinch of salt

2 eggs, beaten

1 tbsp milk

Preheat the oven to 140C/Gas 1. Grease and line a 20cmx20cm cake tin.

Put the butter, sugar, treacle and syrup and heat gently until the butter is melted. Don’t let it boil.

Mix the oats, flour, ginger, spice and salt together in a bowl and add the contents of the pan, stirring well until the dry ingredients are well coated.

Mix in the eggs and milk. Scrape the mixture into the prepared baking tin. Bake for an hour, checking often that it doesn’t get too dark on top (cover it with paper or foil if it threatens to burn).

Leave to cool in the tin, then wrap it well and store in an airtight container. If you can leave it a few days, so much the better – it’ll get stickier with time.

Cut into squares to serve.

If you can't be bothered to do this, go to a shop and buy a toffee apple.

Bonfire Night isn't the world's weirdest cultural celebration...

In other parts of the globe certain countries commemorate events in their own unique way.

El Colacho (Spain)

Catholics are usually baptised to absolve them of Original Sin, but in the Spanish Village of Castrillo de Murcia, babies are laid on pillows on the street, whereupon men dressed as the devil jump over them to rid them of their sins. The bizarre ritual dates back to the 17th century and while surprisingly there have been no reports of injuries, unsurprisingly it is not advocated by The Vatican…

Setsubun (Japan)

This festival is held each year on the last day of winter, 3rd February, where people throw beans to ward away bad luck and bring happiness into their homes. Traditionally they will throw roasted soy beans called fuku mame (fortune beans), while shouting “oni-wa-soto” (get out demons) and “fuku-wa-uchi” (come in happiness).

Battaglia delle Arance (Italy)

The highlight of the historical carnival of Ivrea is the “Battle of the Oranges,” a medieval reenactment that commemorates the city's defiance against an evil tyrant.

Teams of orange-throwers on foot fight an army of orange-throwers on horse-drawn carts, adding up to a total of 5,000 people involved in this sweet, sticky mess. It is estimated that nearly 600,000 pounds of oranges are carted up to the northern city, making it one of the largest food fights in Italy.

Surströmming (Sweden)

Ever smelt something so bad you can taste it? Try eating fermented Baltic herring. In the High Coast of Sweden, a festival is held every August where rotten fish is the main event. This noxious culinary 16th Century tradition takes place outside – for obvious stinky reasons – and the tops are literally popped off of the surströmming (sour herring) tins to the delight of party attendants. Recently cited as one of the most putrid food smells in the world, no wonder it’s an acquired taste.

Rouketopolemos (Greece)

Translated into "Rocket War"; this annual event celebrates Easter by firing off tens of thousands of rockets. What started as a rivalry between two opposing rival Greek churches on the island of Chios, has turned into a yearly fireworks showcase where over 60,000 rockets are fired into the air, in an attempt to hit the bell tower of the church on the opposing side.

Each side claims victory from hitting the other church’s bell tower, but they agree to settle it next year to continue the Easter tradition another year.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News