How successful was Britain’s plan for its own Silicon Valley?

Every city wants a cluster, a concentration of high-productivity firms and workers beavering away in a particular industry in a particular place. Proximity means ideas and productivity growing and spreading. Who doesn’t want their own Silicon Valley?

David Cameron certainly did. In November 2010, he announced the “Tech City” programme, aiming to grow a digital cluster in Shoreditch, east London. The plan was to use branding to get firms in, networking to ensure those ideas get flowing with focused support for high-potential firms.

But did it work? Surprisingly, we’re only now getting the first detailed answer, courtesy of Dr Max Nathan, an academic leading great work on what policy does (and doesn’t) do to drive local economic growth.

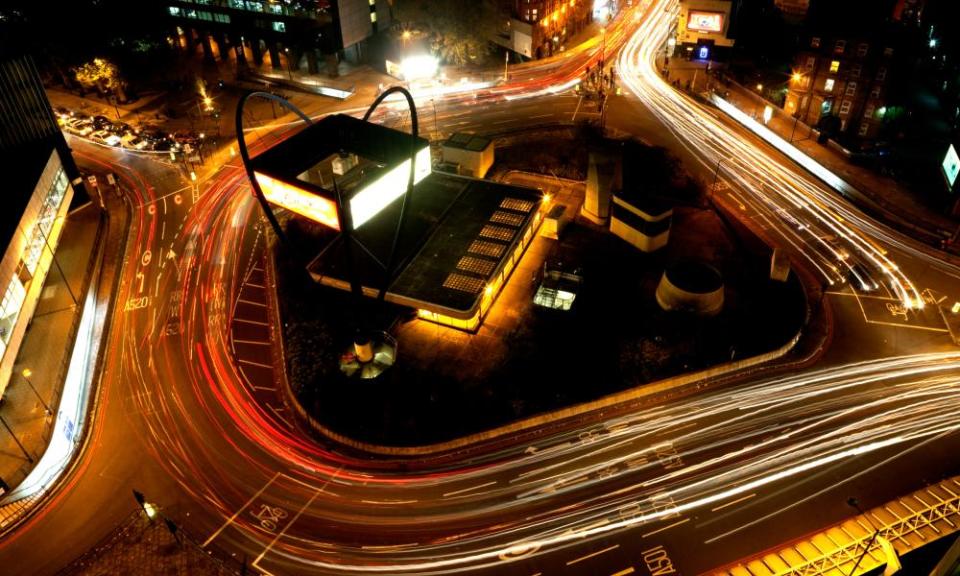

The good news is that Silicon Roundabout (imaginatively named for its closeness to the large Old Street roundabout) has seen lots of digital firms sprouting up, including Deliveroo. There has been an influx of digital tech firms (think software and hardware), adding to existing creative industry strengths. This higher density of similar firms is exactly what a cluster is all about.

But the policy didn’t raise productivity – for small firms, higher rents may have outweighed the pros of being round lots of other hipsters. More importantly, it’s not clear that the policy drove the cluster, rather than just being a response to it already getting going. As the author puts it: “Instead of catalysing the cluster, policy generally rode the wave.”.

The conclusion? A good bit of PR, yes, but the research reminds us that clusters are born of thousands of decisions by firms and people, which we struggle to understand, let alone influence. If only humans were simpler, policymakers would have a much easier life.

• Torsten Bell is chief executive of the Resolution Foundation. Read more at resolutionfoundation.org

Yahoo News

Yahoo News