Super-smart designer babies will be here soon. But is that ethical?

In his new book Blueprint, the psychologist Robert Plomin explains that it is now possible from our individual genome data to make a meaningful prediction about our IQ. When I discussed the topic with Plomin last month, we agreed on the need for urgent discussion of the implications, before genetic selection of embryos for intelligence hits the market. We’re too late. A company called Genomic Prediction, based in New Jersey, has announced that it will offer that service. New Scientist reports that it has already begun talks with American IVF clinics to find customers. They won’t be in short supply.

Before we start imagining a Gattaca-style future of genetic elites and underclasses, there’s some context needed. The company says it is only offering such testing to spot embryos with an IQ low enough to be classed as a disability, and won’t conduct analyses for high IQ. But the technology the company is using will permit that in principle, and co-founder Stephen Hsu, who has long advocated for the prediction of traits from genes, is quoted as saying: “If we don’t do it, some other company will.”

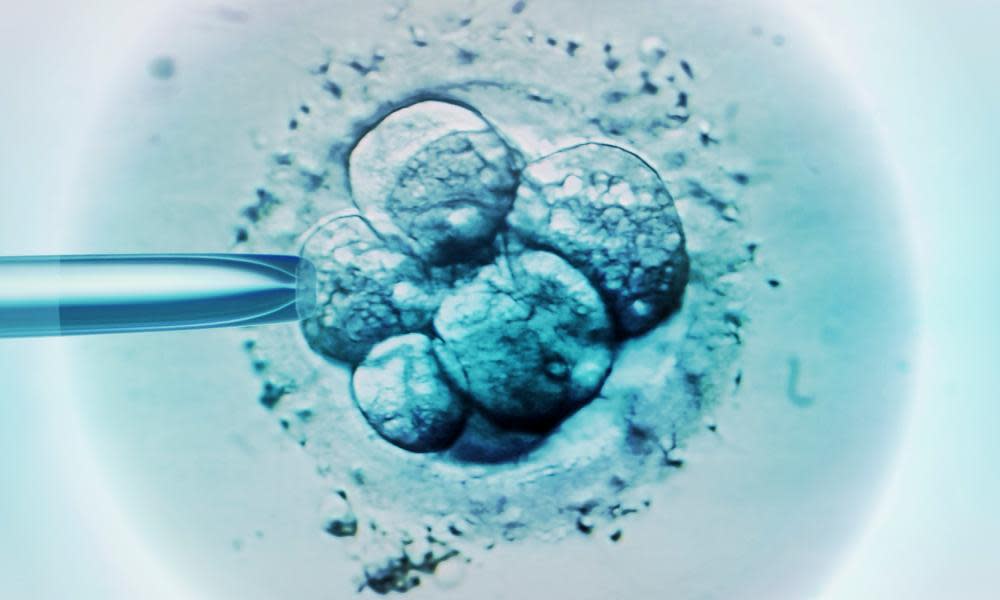

The development must be set, too, against what is already possible and permitted in IVF embryo screening. The procedure called pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) involves extracting cells from embryos at a very early stage and “reading” their genomes before choosing which to implant. It has been enabled by rapid advances in genome-sequencing technology, making the process fast and relatively cheap. In the UK, PGD is strictly regulated by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA), which permits its use to identify embryos with several hundred rare genetic diseases of which the parents are known to be carriers. PGD for other purposes is illegal.

In the US it’s a very different picture. Restrictive laws about what can be done in embryo and stem-cell research using federal funding sit alongside a largely unregulated, laissez-faire private sector, including IVF clinics. PGD to select an embryo’s sex for “family balancing” is permitted, for example. There is nothing in US law to prevent PGD for selecting embryos with “high IQ”.

But what exactly does that mean? The work of Plomin and others has shown over the past few years that correlations exist between the code in our genomes and pretty much any trait you can think of, including IQ and academic achievement. Such links to complex traits (as opposed to single-gene diseases) are usually invisible for any individual gene, but become significant when the influence of hundreds or even thousands of genes are summed in “polygenic scores”.

These relationships are, however, statistical. If you have a polygenic score that places you in the top 10% of academic achievers, that doesn’t mean you will ace your exams without effort. Even setting aside the substantial proportion of intelligence (typically around 50%) that seems to be due to the environment and not inherited, there are wide variations for a given polygenic score, one reason being that there’s plenty of unpredictability in brain wiring during growth and development.

The questions are complicated. When does choice become tyranny?

So the service offered by Genomic Prediction, while it might help to spot extreme low-IQ outliers, is of very limited value for predicting which of several “normal” embryos will be smartest. Imagine, though, the misplaced burden of expectation on a child “selected” to be bright who doesn’t live up to it. If embryo selection for high IQ goes ahead, this will happen.

What’s more, the many genes involved in a polygenic score for intelligence are in no sense “genes for intelligence”; they will have many roles. If you’re “selecting for intelligence” you don’t know what else you might be selecting for, for better or worse.

So the science behind embryo IQ testing is still shaky. But before we get too indignant about the horrors of designer babies, bear in mind that already we permit, even in the UK, prenatal screening for Down’s syndrome, a disability that produces low to moderate intellectual disability. It’s not easy to make a moral or philosophical case that the screening offered by Genomic Prediction for low IQ is any different. There may be more uncertainty but, given not all IVF embryos will be implanted anyway, can we object to tipping the scales? And how can we condone efforts to improve your child’s intelligence after birth but not before?

The questions are complicated. How to balance individual rights against what is good for society as a whole? When does avoidance of disease and disability shade into enhancement? Should society be more receptive to disability rather than seeing it as something to be eradicated? When does choice become tyranny?

In the UK we are extraordinarily lucky to have the HFEA, which frames binding regulation after careful deliberation and acts as a brake so the technology does not outrun the debate. “Embryo selection needs robust regulation that society can be confident in,” says Ewan Birney, director of the European Bioinformatics Institute in Cambridge. Leaving a matter such as this to unregulated market forces is dangerous.

• Philip Ball is a science writer

Yahoo News

Yahoo News