Sussex PCC who suffered stalking says new law does not go far enough and calls for overhaul of crime treatment

The new Stalking Protection Bill does not go far enough according to the Sussex police and crime commissioner (PCC), herself a victim of stalking.

Katy Bourne said she was failed by the police and prosecutors when she reported her own case.

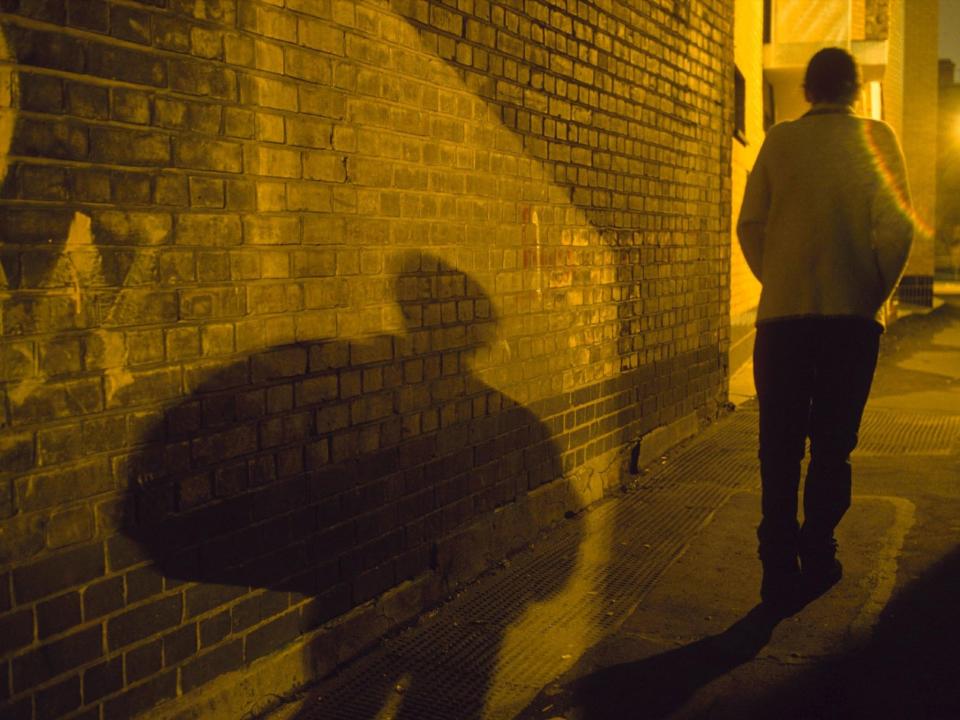

She argued the issue of stalking was routinely trivialised and shrouded by misinformation – saying it is regarded as a “nuisance rather than a crime” and prosecutors fail to understand the patterns of behaviour tied to stalking.

Ms Bourne’s comments come as the number of recorded stalking offences has trebled in England and Wales since 2014 but prosecution rates have plummeted.

Stalking is one of the most frequently experienced forms of abuse – with official figures showing one in five women and one in 10 men will be stalked in their lifetime.

A 2017 study by the University of Gloucestershire found stalking was identified in the runup to 94 per cent of the 358 criminal homicides examined.

Ms Bourne said she was eager for a stalkers register – which would help police track and monitor serial perpetrators – to be implemented but the bill fails to include this.

The Conservative politician said that while she fully supports the Stalking Protection Bill, more work needs to be done to address the “insidious crime”.

She said: “There is no legal definition of stalking, meaning it is very difficult for people to pin down what the crime is. Different agencies use different terminology to describe it, making it harder to address.

“I fully support the bill, but while legislation is important, it is equally important to see how the bill is understood and applied. We need to work with police and prosecutors and all agencies across the board to give the public the confidence to come forward. There is always more that needs to be done. We can’t afford to be complacent.”

The bill – which is being sponsored by Tory MP Dr Sarah Wollaston and will have its third reading in parliament later this week – aims to deal with a gap in the law on stalking, which is predominantly configured around stalking by ex-partners, by focusing more on the issue of “stranger stalkers”.

It includes anti-stalking orders which can be issued “on the balance of probability” to curb stalking when it may not be possible to reach the “beyond reasonable doubt” standard of proof required for criminal cases.

They could cover banning people from approaching a person and their friends and family – online or in real life – and breaches could result in perpetrators facing up to five years’ imprisonment.

Rachel Horman, a solicitor who has represented a number of high profile stalking victims, hit out at the new bill for not being far reaching enough.

Ms Horman, of national stalking advocacy service Paladin, said she was fearful it would result in police using orders instead of convictions.

“Paladin welcomes the new bill but we do not think it goes far enough. We are concerned the police will use orders instead of charges. While the protection order is designed to keep the victim safe, without a criminal conviction they will not be on the perpetrator’s register.

“The protection orders are part of the civil route – they are completely separate to the criminal process. We want them to be used as well as criminal convictions but at the moment prosecutions are few and far between, and we do not want it to get worse.”

She said it was common for alleged perpetrators to be charged with stalking but for charges to be dropped to harassment when cases reach court.

“Harassment charges are less serious than stalking – there is a difference in the sentence – and the defendant will plead guilty to harassment if they agree to drop the stalking. It is a prevalent problem,” she said.

“There is also a problem with underreporting. On average, a victim has experienced over 100 incidents before they even report it to the police. And then when they do go to the police, they do not do anything.”

She said the overwhelming majority of victims get a poor response from the police who do not perceive stalking as a proper crime. “They issue a warning through a police information notice but it often increases the risk for a victim because it angers the stalker. If you look at a lot of the murders which have happened, a warning notice was issued before,” she said.

According to Home Office figures, in 2014-15 there were 2,882 recorded offences of stalking, but by 2017-18 that figure had risen to 10,214.

But the percentage of people charged has radically fallen – of the 6,702 cases in which a charge could have been brought, only 1,692 offences (25 per cent) led to one. The percentage was considerably higher in 2014-15, when 49 per cent of reported crimes resulted in a charge. The figure dropped to 32 per cent in 2015-16 and 30 per cent in 2016-17.

Matthew Taylor, a man who spent years harassing Ms Bourne online, was sentenced for defying an injunction to stop his campaign last month. He was sentenced to four years in prison – with one month remitted if he removes the online material – suspended for two years.

According to Ms Bourne, Mr Taylor started publishing lies and harassment when he unsuccessfully ran against her for the PCC role back in 2011.

“He has accused me of being a paedophile, a murderer, a prostitute in online posts, and called me a Nazi sympathiser,” she said.

In hundreds of online blog posts submitted as part of her evidence, his claims included that she was a “prostitute”, a “nasty Nazi party sympathiser” and the “biggest drug dealer in Sussex”.

“There are four behaviours which make stalking unique: fixated, obsessive, unwanted, repeated. This is what he started to become. It was repeated and relentless. He was not just going to take me down professionally but also personally. It got worse and worse. My husband and I got into a routine where I would phone him when I got to an event and when I left the event. You try doing that every day of your life. It chips away at you.”

She said she was disappointed by the way the police dealt with her case.

“They only looked at the six months of offending. When the police passed the case to the CPS it said there is insufficient evidence,” she said.

“The CPS needs to change the way it treats victims of stalking. It should have seen this as a progressive offence that wears the victim down. The whole process has been really wearing – I have huge sympathy for other victims and how it feels to have the whole system not respond in a compassionate, constructive way.”

Just 1 per cent of stalking victims are estimated to seek help. A joint inspection last year by HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate and HM Inspectorate of Constabulary found none of the 112 cases they looked at were dealt with properly.

Care for the victim was judged inadequate in 95 per cent of those cases and three-quarters of them were not investigated by detectives.

A CPS spokesperson said: “Stalking and harassment are some of the most challenging offences CPS and police deal with. Last year we handled almost 12,000 stalking and harassment offences and aim to provide people affected with the greatest possible protection from repeat offending.

“We have developed a new protocol with police which means a fundamental shift in how we deal with cases – this includes considering if they involve stalking from the outset. It also emphasises the need to properly record, identify and investigate offences of stalking and harassment.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News