Sylvia Pankhurst letters reveal concerns about phone-tapping

The socialist suffragette and human rights campaigner Sylvia Pankhurst lobbied the British government in the 1930s about eavesdropping on phone conversations, newly unearthed letters reveal.

Pankhurst, who was monitored by MI5 for decades, expressed concern about a case in which a suspicious solicitor had set up a duplicate line so he could listen to and record his wife’s conversations with a lover.

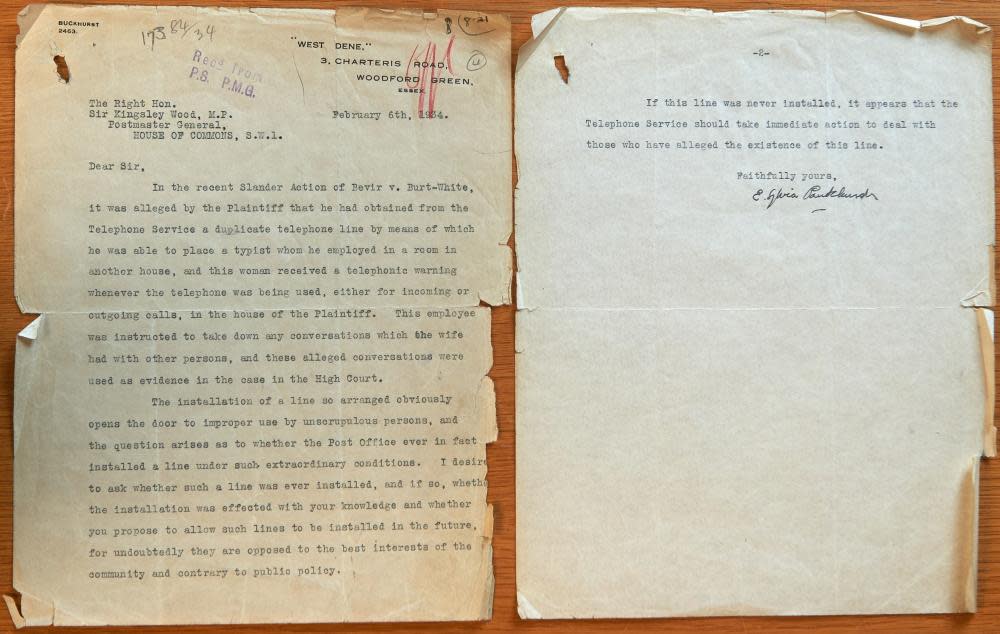

In 1934, Pankhurst wrote to the postmaster general flagging up the case and raising concerns that such a practice could open the door to “improper use by unscrupulous persons”. She said it was against the best interests of society and against public policy.

It is possible Pankhurst took an interest in the case because she feared she and colleagues could be targeted with similar tactics.

The documents were unearthed by the academic Sarah Jackson while working at the BT Archives in the old Holborn telephone exchange in central London as part of research fellowship funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC).

Jackson, who is writing a book about literature and telephony, was searching through files relating to phone-tapping when she came upon letters from Pankhurst.

“They referred to a rather seedy case in which a Harley Street gynaecologist was struck off for having an affair with a patient,” she said. “The patient’s husband, a solicitor, had found out and persuaded the Post Office, which was then in charge of the telephone system, to install an extra line.”

Every time the extra line rang a bell sounded, alerting a secretary in a neighbouring house. The secretary listened in to the call and noted the conversations between the wife and her lover in shorthand. In one a man, presumably the doctor, was heard telling the wife: “I will ring you later, my beautiful.”

Pankhurst was clearly alarmed and wrote to the postmaster general, the MP Kingsley Wood, at the House of Commons.

She told him: “The installation of a line so arranged obviously opens the door to improper use by unscrupulous persons and the question arises as to whether the Post Office ever in fact installed a line under such extraordinary conditions.

“I desire to ask whether such a line was ever installed, and if so, whether the installation was effected with your knowledge and whether you proposed to allow such lines to be installed in the future for undoubtedly they are opposed to the very best interests of the community and contrary to public policy.”

An official replied insisting it was routine for extra lines to be installed so they could take calls in different rooms. But Pankhurst wrote again saying she had an extension but that the buzzer system used by the solicitor seemed “quite special.”

Notes found by Jackson show officials decided not to reply. One suggested that the best tactic was to “stonewall” Pankhurst.

Jackson, an associate professor at Nottingham Trent University, said MI5 had monitored Pankhurst’s movements and intercepted her letters in the 1930s and 40s. There are references in MI5’s files to “telephone checks”. Jackson said: “It’s pure speculation but it’s tempting to think she had an inkling she was being monitored.

“Her letters are polite and firm. She’s clearly incredibly intelligent and a force to be reckoned with. Just after finding the letter I came upon the story of the MP [Steve Baker] who keeps his mobile phone in the microwave so he can’t be monitored. It shows that concerns about surveillance have been there for decades and are still very much with us.”

Sylvia became estranged from her mother, Emmeline, and her sister, Christabel, over her opposition to the first world war and her pursuit of socialist ideals. George Bernard Shaw once compared her to Joan of Arc.

As well as championing the cause of women’s suffrage, she enraged diplomats and the security service in the 1940s with a campaign on behalf of Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia. In an MI5 file released in 2004 a document from a Foreign Office official described her as a “horrid old harridan”, with the official saying he hoped she would be “choked to death with her own pamphlets”. Pankhurst died in 1960 aged 78.

Prof Roey Sweet, the AHRC’s director of partnerships and engagement, said: “Sylvia Pankhurst is generally remembered today simply as a militant suffragette, but the exciting discovery of these letters reminds us that her fight for women’s political rights was part of her lifelong commitment to socialist and revolutionary politics, pacifism and internationalism.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News