Is Tamino the heir to Jeff Buckley?

Few voices make you stop in your tracks. For some, it only happens once or twice in their lifetime, to hear something with a visceral, immediate power so unique that it seems otherworldly. Tamino is one of those voices.

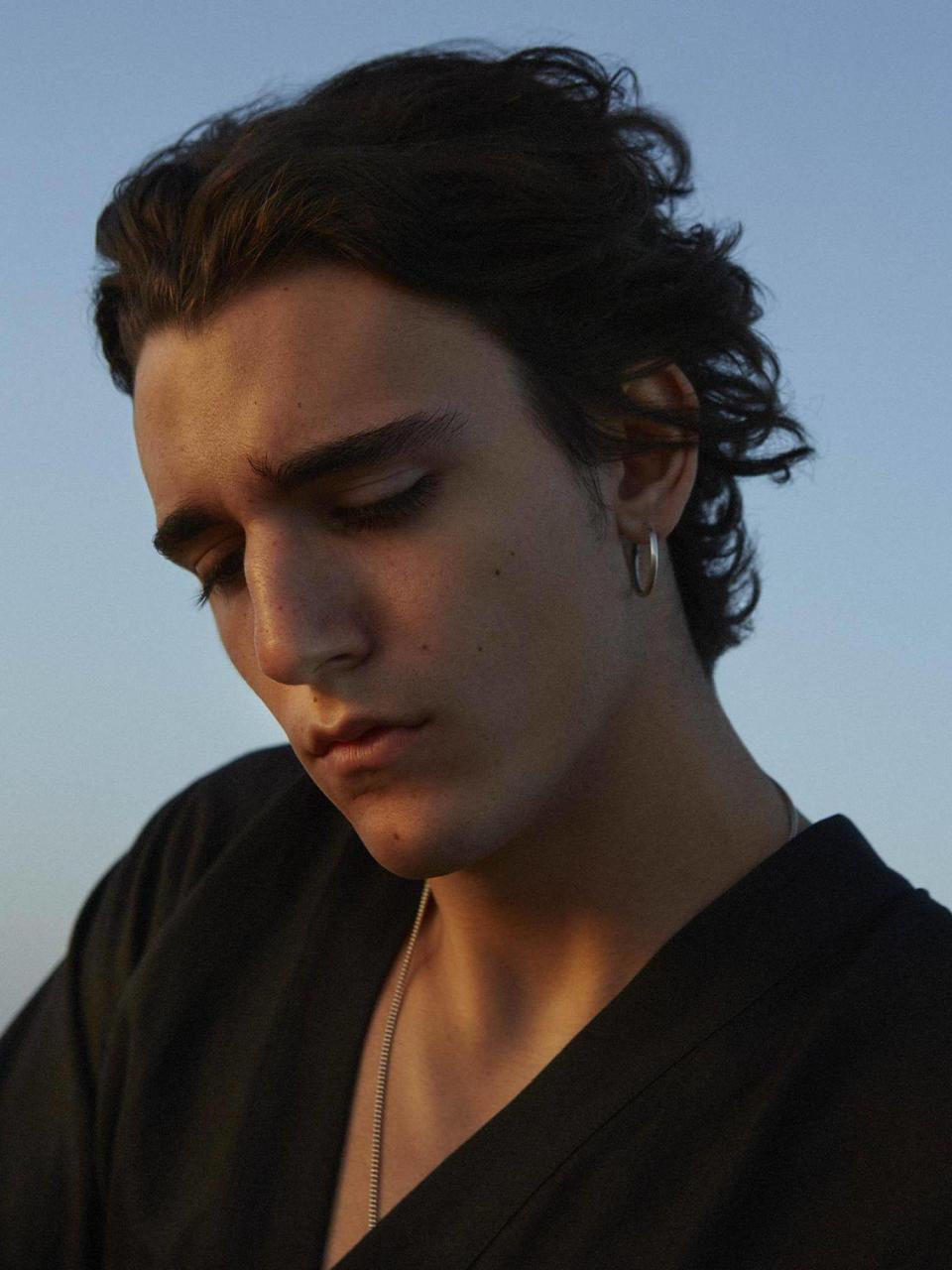

Born Tamino Moharam Foud, the Belgian-Egyptian artist was named after the principal character, a prince, in Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute. He’s strikingly beautiful – think Jeff Buckley with Egyptian heritage – and the 21-year-old has a soulful, languid gaze that brightens as he speaks, with an articulacy and comprehension of music that defies his age.

His debut single “Habibi” (“my love” or “sweetheart” in Arabic), received considerable airplay in Belgium before being picked up in the UK and elsewhere in Europe... likely because it sounded like nothing else in popular music. Before he’d even performed a show in the UK, record labels clamoured to win him over.

“There are people who have told me they love my falsetto,” he acknowledges, referring to one particular, obscenely high note on “Habibi”, that causes audible gasps from audience members when he performs it live. “They ask why I don’t use it more often. But I don’t want it to be like a trick, or some acrobatic thing. I really have to avoid it becoming that. If it feels right, then I sing that way.”

On YouTube, the lyric video for “Habibi” has received more than a million streams, with Tamino’s voice drawing comparisons to Jeff Buckley, Thom Yorke and Matt Bellamy of Muse. Not a bad trio to be ranked alongside, for an artist about to release his debut album.

Amir features an orchestra, Nagham Zikrayat – many of whom are refugees from Iraq and Syria. They first reached out to Tamino to ask if he wanted to sing the songs of his late grandfather, the famous Egyptian singer and actor Muharram Fouad.

His father’s side of the family are all musically gifted, Tamino says, but it was his grandfather who achieved fame in the 1960s during the golden age of Egyptian cinema, and was described at the height of his fame as “The Sound of the Nile”. On stage, Tamino often plays his grandfather’s Resonator guitar, gifted to him after he discovered it in a cupboard during a visit to his grandmother.

It’s fitting that the orchestra’s name means “musical nostalgia” in Arabic: Tamino’s music draws on the old-world romance of his grandfather’s music, but also embodies the genre-less quality of much modern pop. The musical heritage that is so essential to his sound comes to life in the dramatic, sweeping instrumentation on a song like “So It Goes”; haunting, graceful violins, bold drum beats and the shimmer of a tambourine transport the listener entirely.

“If it was a Western orchestra, we would have to add every detail on the page, or they would have done it exactly as it was written, really flat without forte or crescendo,” Tamino says. “I wanted to recreate the Firka – the traditional Arabic orchestra from the golden age, where they really accompanied the singer.”

The tonal inflections in the instrumentation match the ones you hear in Tamino’s own voice – Arabic quarter notes that slipped in without him realising when he practised. He trained at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels, aged 17, joking that he was “terrible” before he was taught how to use proper breathing exercises. Yet he has always sung in essentially the same way.

“I’m very flattered when people compare me to artists I look up to,” he says. “But I’ve never really listened to someone and said, ‘that’s what I want to do’. I got to know many of those bands when I was a teenager: Radiohead, Nirvana, Tom Waits, Leonard Cohen, The Beatles. Songwriting is something you have to learn. But singing, for me, comes from a very different place.”

His paternal grandmother, who is Lebanese, recently came to one of his shows for the first time, in Istanbul, and Tamino says he never saw her smile so much. “She said, ‘you remind me so much of your grandfather,’” he recalls. “I think that’s what I inherited – something about the intensity of the way I sing.”

Contributing a more modern style of performance on the album is Radiohead bassist Colin Greenwood, who was introduced to Tamino via a mutual friend who brought him along to a concert in Antwerp.

“He came up after the show with my vinyl and also a CD, and he was so kind,” Tamino says with a nervous chuckle; his graceful demeanour slips for a moment to reveal a teenage-like awe, as he recalls the moment he asked Greenwood to play bass on “Indigo Night”.

The final song on the album, “Persephone”, references the Greek myth in which the daughter of Zeus is abducted by Hades and taken to the underworld. Ironically, in The Magic Flute, his namesake rescues the princess Pamina from captivity under the evil high priest Sarastro. But in “Persephone”, Tamino becomes Hades, keeping the titular character captive.

“It started out as a very personal song,” Tamino says. “I saw parallels with the myth, and I used it because I wanted to hide a bit, to protect myself, maybe. I thought I could sing from the perspective of Hades and still be myself as well.”

There’s a conflict in the lyrics that falls somewhere between nihilism and a more romantic state of being: “The romantic side is where you’re floating, but you can fall at any moment. That makes you vulnerable,” he says. “With nihilism, you’re less vulnerable... but you’re not living.”

“And the other theme, if you want to call it that, is that I’m really young,” he adds. “I’m dealing with ‘firsts’ all the time. So, there’s a lot of naivete in the lyrics, which I didn’t want to polish. Amir had to be an album that I could only have written now.”

Amir is out on 19 October via Communion Records

Yahoo News

Yahoo News