Tchaikovsky: where to start with his music

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-93) was the composer who put Russia on the international musical map with his uniquely personal style – profoundly Russian in idiom but engaging with, and embracing, western European symphonic traditions. His music encapsulates wonder and joy, as well as passion, neurosis and profound tragedy: the fatalistic quality of some of his later works reflects an often unhappy life, the complexities of which have provoked extensive analysis, some of it sensationalist. Recent scholarship has revealed that he was by no means always ill at ease with his sexual orientation, as was previously thought.

The music you may recognise

Emotionally direct, and an incomparable melodist, Tchaikovsky is among the most popular of composers. His best-known works include his First Piano Concerto, the ballets Swan Lake, The Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker, the 1812 Overture (the one with the cannons), the Violin Concerto, and his Sixth “Pathétique” Symphony. His music has advertised everything from cereal to chocolate, and been used in countless films. Ken Russell’s The Music Lovers (1970) is an inaccurate, overwrought biopic; Swan Lake forms the basis for Darren Aronofsky’s Black Swan, and, several decades earlier, was famously parodied in Morecambe and Wise’s The Intelligence Men.

His life

He was born in Votkinsk, the second of six children of a metal works manager and his second wife. Fascinated by music in early childhood, he was composing as early as four. Aged 10, he was sent over a thousand miles away to the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in St Petersburg, with a view to his becoming a civil servant. The trauma of being separated from his mother was compounded by her death from cholera four years later.

While working at the Ministry of Justice, he took private composition lessons, though a major turning point came in 1862 with the foundation of the St Petersburg Conservatory, at which he immediately enrolled, graduating in 1865, and so impressing his teacher, Anton Rubinstein, that the latter recommended Tchaikovsky to his pianist brother Nikolay, who appointed him professor of harmony at the new Moscow Conservatory, a position he held until 1878.

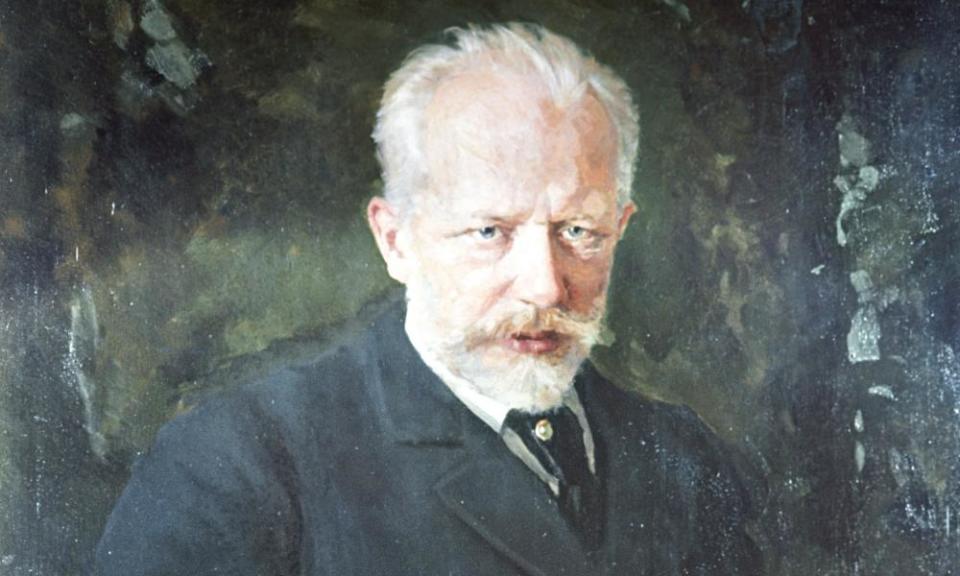

Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Highly strung, he was prone to self-doubt, which plagued him throughout his career. His melancholy First Symphony “Winter Daydreams”, begun in 1866, marked the emergence of his individual voice. He always claimed it cost him more anguish than any of his other works. The first of his operas, The Voyevoda, was performed at the Bolshoi in 1869, but Tchaikovsky subsequently destroyed the score, reusing some of its material in later works.

His academic position, meanwhile, resulted in his being viewed warily by the nationalist, largely self-taught circle of composers, headed by Mily Balakirev and including Mussorgsky and Borodin, who dismissed conservatoire training as western and therefore “foreign”, though they admired Tchaikovsky’s Second Symphony “Little Russian”, rooted in Ukrainian folk music. It was Balakirev who suggested to Tchaikovsky the subject of Romeo and Juliet, begun in 1869, and the first of a series of symphonic poems that includes The Tempest (1873), Francesca da Rimini (1876) and Hamlet (1888).

His beautiful Third Symphony “Polish” dates from 1875, as does his First Piano Concerto, intended for Nikolay Rubinstein, who initially rubbished it as unplayable, a judgment he later regretted. It was taken up by the German pianist-conductor Hans von Bülow, who gave the first performance in Boston the same year. Swan Lake, meanwhile, was considered overly symphonic at its 1877 premiere, and only became successful when it was re-choreographed by Marius Petipa for the Mariinsky theatre in 1895, two years after Tchaikovsky’s death.

… and times

Tchaikovsky’s career as a composer coincided with the great 19th-century flowering of Russian literature, set in motion by Pushkin and Lermontov in the 1820s and 30s and dominated in the 1860s and 70s by Dostoevsky and Tolstoy. Tolstoy had been moved to tears by the Andante Cantabile from Tchaikovsky’s First String Quartet, and, while on a visit to Moscow in 1876 to oversee the publication of Anna Karenina, arrived unannounced at the Conservatory and insisted on speaking with the composer. They met several times but no record of their conversations survive. In his later correspondence, Tchaikovsky admitted to being overawed and also professed himself puzzled by Tolstoy’s ambivalence to Beethoven.

The year 1876 also marked the start of his relationship with Nadezhda von Meck, widow of a wealthy railroad engineer and a great admirer of Tchaikovsky’s music, who offered him an annual allowance on condition that they never meet.

In 1877, there was a crisis when Tchaikovsky decided to marry Antonina Miliukova, a former pupil who had written him several love letters. Homosexuality was illegal in Russia, though accepted in aristocratic and artistic circles. Of necessity, Tchaikovsky’s relationships with men had always been, and were to remain, discreet, and his decision is frequently ascribed to a combination of guilt and a fear of public exposure at a time when his reputation was steadily growing. The marriage, however, was disastrous: the couple separated after nine weeks, but never divorced. Tchaikovsky, however, subsequently came to accept “that which I am by nature”, as he told his brother Anatoly in 1878. Nothing in his later correspondence suggests a man troubled by his sexuality.

At the time of his marriage, he was working on his Fourth Symphony and had begun the opera Eugene Onegin, both completed in 1878. Onegin, based on Pushkin’s verse novel, is a work of deep, contained sadness, remarkable for its psychological realism and restrained dramaturgy that to some extent brings it closer to the later theatre of Chekhov than to anything else conventionally operatic. The symphony is dominated by the idea of fate, represented by a fierce motto hurled out by the brass at the start, and the immense first movement, with its spectral dances and intimations of disillusionment, twists conventional symphonic structure into something radically new and intensely personal.

Von Meck’s patronage, meanwhile, allowed Tchaikovsky to give up his teaching post and travel extensively in Europe each winter, returning to summer in Russia, renting houses first at Maidanovo, then Klin, both north of Moscow. The year 1880 saw the completion of the Second Piano Concerto, more overtly flamboyant than the First, and the composition of both the Serenade for Strings, and the 1812 Overture, premiered two years later to mark the 70th anniversary of the expulsion from Russia of Napoleon’s army. Profoundly shocked by the death of Nikolay Rubinstein in 1881, Tchaikovsky wrote his haunting A Minor Piano Trio dedicated “À la mémoire d’un grand artiste”, while the turbulent Manfred Symphony, based on Byron’s poem, was premiered in 1886.

The theme of fate surfaced again in his original plans for his Fifth Symphony of 1888 and coloured the opera The Queen of Spades (1890), a brooding, obsessional masterpiece, also based on Pushkin. The year 1890 also saw the first performance of The Sleeping Beauty, his most successful ballet in his lifetime, though the same year Von Meck, seriously ill with tuberculosis and fearing potential bankruptcy, broke off both her patronage and her friendship with Tchaikovsky, which caused him terrible distress. His international career continued to flourish, however. In 1891, he visited the United States to conduct performances of his own works at the opening of Carnegie Hall, and in 1893 was awarded an honorary doctorate at Cambridge University. His final stage works, the opera Iolanta and the ballet The Nutcracker were first performed in a double bill in St Petersburg in 1892.

Tchaikovsky’s last completed score, the Sixth Symphony, is irrevocably associated with his death nine days after the premiere, ostensibly from cholera after drinking unboiled water. The work is very much a mature tragic statement, though the violence of the first movement’s development section and, in particular, the despairing slow finale inevitably came to be regarded as premonitory. Several theories that Tchaikovsky took his own life, possibly to avoid a sexual scandal, have been advanced over the years, though none have been conclusively proved.

Why he still matters

Tchaikovsky changed the parameters of Russian music, much of which takes him as a point of departure. The symphonies of Shostakovich and Prokofiev are unthinkable without him. His ballets, among the greatest ever composed, dominate the repertory worldwide and brought new seriousness and integrity to a genre previously dismissed as slight, paving the way for the later achievements of Glazunov, Stravinsky, Ravel, Prokofiev again and beyond. Though many of Tchaikovsky’s operas are still comparative rarities outside Russia, Eugene Onegin and The Queen of Spades are central to the repertory of every major opera house in the world.

Great performers

There are major symphony cycles from conductors as far apart as Herbert von Karajan, Mstislav Rostropovich and Mariss Jansons, though Valery Gergiev’s LSO Live set of the first three was much admired when it was released in 2012 and Evgeny Mravinsky’s recordings of Nos 4-6 are particularly outstanding. Emil Gilels’s fiery performances of the piano concertos still take some beating. I have a huge soft spot for Ernest Ansermet’s exquisite recordings of the ballets, though there are superb modern alternatives from Gergiev and Neeme Järvi. Semyon Bychkov’s Eugene Onegin, with the late, great Dmitri Hvorostovsky in the title role, is hauntingly beautiful, and Rostropovich, Gergiev and Jansons have all made formidable recordings of The Queen of Spades.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News