Terry Hall, singer with the Specials, who fused punk energy with ska rhythms and politically charged lyrics to galvanising effect – obituary

Terry Hall, who has died following a short illness aged 63, was the lead singer of the Specials, a mixed-race band who emerged from Coventry in the late 1970s and whose “two-tone sensibility” was influential in fostering anti-racist sentiment in the 1970s; despite being adored by mod-attired teenage fans, their gigs were characterised by punch-ups in the crowds, stage invasions and confrontations with members of the National Front.

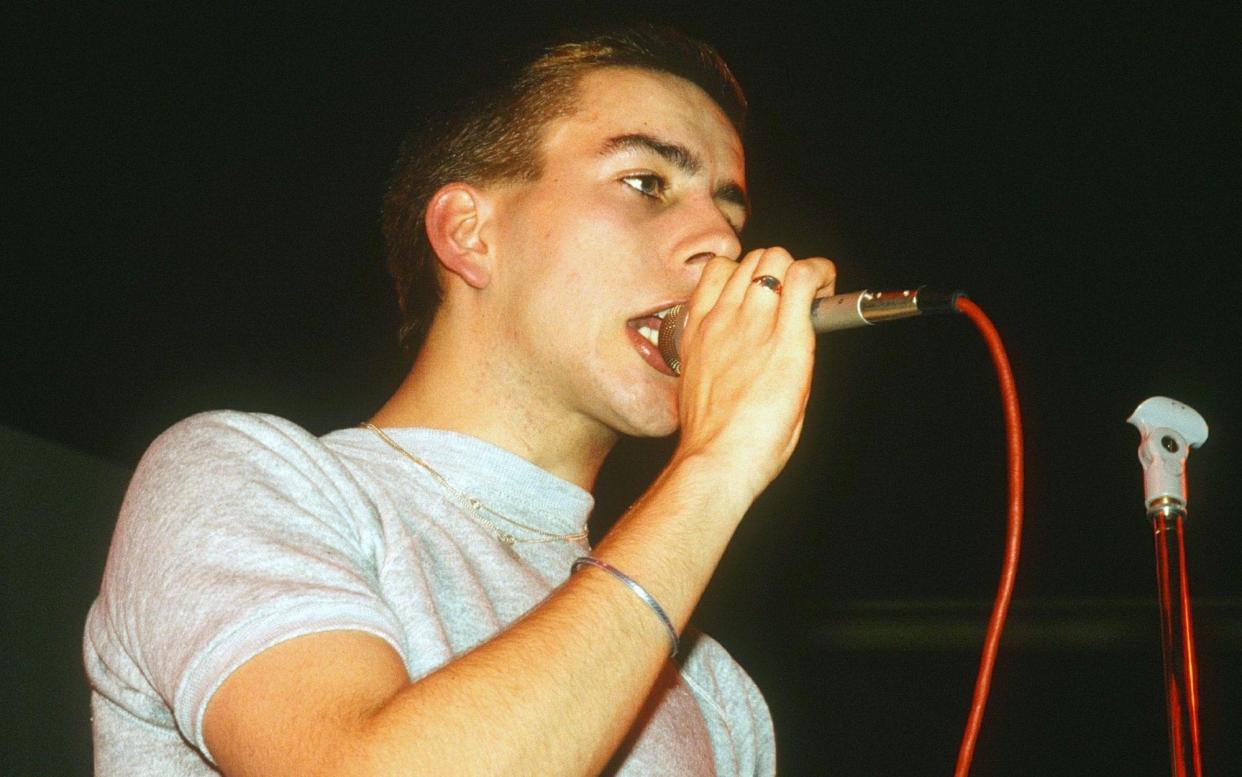

The Specials’ songs were a thrilling fusion of furious punk energy, exuberant Jamaican rhythms and politically sharp lyrics. At their heart was the ethereal voice of Hall, with his plangent warble – part choirboy, part bootboy – and deadpan, saturnine features. He was also sartorially striking. “Whereas all the other punks were wearing leather jackets, he would be wearing a patent leather jacket,” Jerry Dammers, the band’s main songwriter, recalled.

Hall was working in a coin dealer/stamp shop by day and playing in a punk band called Squad by night when he was spotted by Dammers, who had formed the Coventry Automatics with Lynval Golding (guitar) and “Sir” Horace “Gentleman” Panter (bass). Dammers recalled recruiting him with the pun: “Philately will get you nowhere.”

The group expanded to include Roddy “Radiation” Byers (guitar), Neville Staple (percussion and vocals) and John Bradbury (drums), and soon changed their name to the Coventry Automatics AKA The Specials, which was shortened to the Specials.

Their first demos were recorded by a Coventry DJ called Pete Waterman and their debut single, Gangsters, a reworking of Prince Buster’s Al Capone, was released in 1979 and championed by John Peel on Radio 1. Hall and Panter hand-stamped the 5,000 white sleeves at Panter’s flat. Then came their debut studio album, The Specials, produced by Elvis Costello, that included A Message to You Rudy and Too Much Too Young, which made allusions to contraception – “Try wearing a cap!” – and was their first No 1.

While these songs cut to the quick of young people’s daily experiences in many British cities, Coventry remained the centre of their world. The Parson’s Nose chip shop, for example, was immortalised in Friday Night Saturday Morning with the line: “But 2 o’clock has come again/ It’s time to leave this paradise/ Hope the chip shop isn’t closed/ Cause their pies are really nice.”

For three turbulent years the Specials were the coolest band in Britain, releasing two Top Five albums and seven Top Ten singles. They also had their own label, 2 Tone Records. Amid the 1981 summer riots in Brixton and Toxteth the sinister lyrics of Ghost Town, their second No 1, were eerily prophetic: “This place is coming like a ghost town/ No job to be found in this country/ Can’t go on no more/ The people getting angry.”

It was the band’s last hit. Theirs had always been a fractious union of strong characters, all from different social and racial backgrounds. They were in the Top of the Pops dressing room when Hall, Staple and Golding announced their departure to form a new band, Fun Boy Three, their name thought to be an ironic reference to Hall’s often melancholic demeanour. “It felt like the perfect moment to stop the Specials part one,” Hall said. “We’d gone from seven kids in the back of a van to being presented with gold discs and I never felt massively comfortable with that.”

Terence Edward Hall was born on March 19 1959 in Coventry, where most of his family worked in the car industry. He was a promising footballer and tried out for West Bromwich Albion. He also passed the 11-plus, though his parents refused to send him to a grammar school and he was educated at Sidney Stringer Comprehensive School.

Aged 12 he was taken by a teacher to France and abused for three days by a paedophile ring before being left by the roadside. It was a trauma reflected in Fun Boy Three’s song Well Fancy That with the line: “On school trips to France/ Well fancy that/ You had a good time/ Turned sex into crime.”

He then dropped out: “I was sort of drugged up then on Valium for about a year.” Mental illness became a recurring theme: in his twenties he had a breakdown; in his thirties he self-medicated with gin; and in later years he took anti-psychotic pills.

Bipolar disorder was diagnosed, which explained much of his outrageous behaviour on the road. “The greatest one was when I was trying to break the window at Hamley’s toy store at four in the morning because I saw a teddy bear and decided that I wanted to spend the rest of my life with him,” he recalled. “He was a six-foot bear wearing a dickie bow. Who wouldn’t want to live with him? But that didn’t go down well with the police.”

Hall drifted through short-term jobs, including a week as an apprentice hairdresser. “There was a salon called Barbarella’s which had loads of dolly birds working there, and I thought this is great,” he said. Disillusion set in when he was sent to the men’s salon and found himself “just washing nicotine out of old blokes’ hair”.

He lasted a few months as a bricklayer but only 17 minutes as a quantity surveyor. “It was freezing and [the boss] said, ‘Take your hands out of your pocket’ and I was like ‘F--- you’ and that was the end of my job.” After seeing the Sex Pistols perform at Lanchester Polytechnic (now Coventry University) in November 1976 he decided to pursue music.

Fun Boy Three took a more minimalist approach to the ska sound than the Specials and enjoyed more ironic hits such as The Lunatics (Have Taken Over the Asylum) and It Ain’t What You Do (It’s the Way That You Do It), which they recorded with Bananarama. But Hall was soon on the move again and in 1984 formed the Colourfield, releasing the studio album Virgins and Philistines that included the hit single Thinking of You.

Five years later he teamed up with the American actress Blair Booth and jeweller Anouchka Grose and began recording as Terry, Blair & Anouchka, though their debut album Ultra Modern Nursery Rhymes (1990) did not chart.

By the mid-1990s Hall was concentrating on his solo career, though his interest in music of other cultures resurfaced one more time on The Hour of Two Lights, a fascinating collaboration with the Asian underground producer Mushtaq that included contributions from an Algerian rapper, a Polish gypsy band, a Tunisian singer, a 12-year-old Lebanese girl and the clarinet of Eddie Morden, who had played the original Pink Panther theme.

The Specials reunited in 2009, though without Dammers, and their last album, Protest Songs 1924-2012 (2021), featured a typically heartfelt take on protest music with songs of grievance by the Staples Singers, Bob Marley, Leonard Cohen, Frank Zappa and Talking Heads.

Yet their famously dour and laconic frontman was pessimistic about music’s power to affect political change. “There were protest songs before we were born that sound as relevant today as they did at the time,” he said. “It can echo a feeling, it gives you something to think about, but real change is hard. There’s always something to protest about.”

Terry Hall, a lifelong Manchester United supporter, is survived by his wife Lindy Heymann, a film director, and their son, and by two sons from a previous marriage that was dissolved.

Terry Hall, born March 19 1959, died December 18 2022

Yahoo News

Yahoo News