Theatres that made us: from London's Royal Court to Birmingham Rep

‘New writing to blow the bloody doors off’

Daniel Mays: I couldn’t get arrested in the six months after drama school – a barren time full of self-doubt. Then came an audition for the Royal Court’s Young Writers festival. I was cast alongside Sian Brooke, Liz White and Rafe Spall, and my love affair with the Court began. Under the leadership of artistic directors Ian Rickson and Dominic Cooke, I performed seven plays there. Its energy and work ethic fitted me like a glove. The Court gave me incredible opportunities and the greatest memories any young, wild, aspiring actor could hope for.

That beautifully designed auditorium and stage with its glorious back wall. A sneaky fag in the fire escape underneath Sloane Square. Getting to watch the other amazing new plays that you weren’t in. Psyching yourself up on the top floor balcony just before press night. Performing in the same building as Michael Gambon. That black-and-white portrait of George Devine. Always the writing.

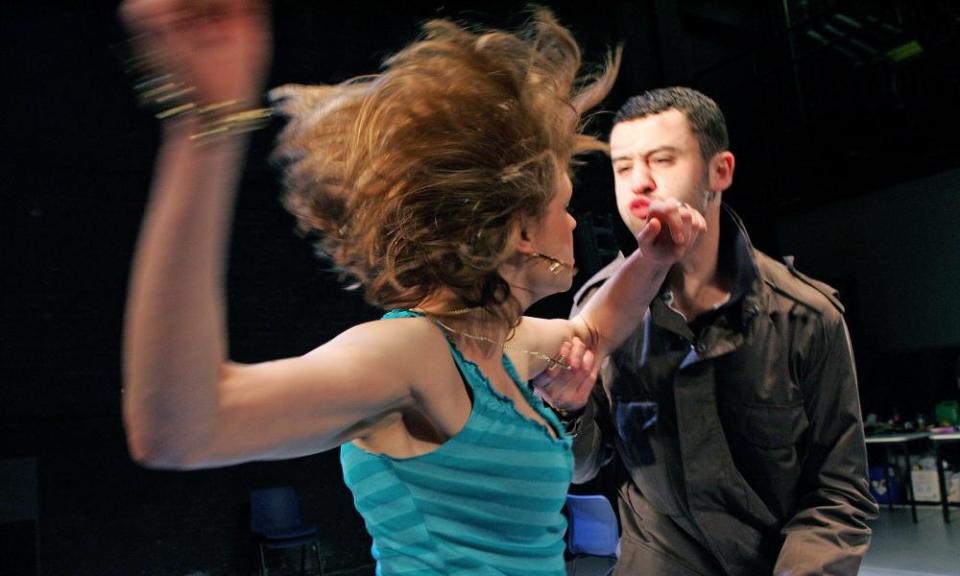

The Court’s 50th-anniversary year held the most significance for me. Having only acted in the theatre upstairs, I was desperate to hit the main stage. The stars aligned and I was cast in two back-to-back plays: Jez Butterworth’s The Winterling and Simon Stephens’ searingly brutal Motortown, which seemed to encapsulate everything that is exceptional and dangerous about the Court. New writing to blow the bloody doors off and for me the role of a lifetime. Rehearsing one in the day and performing the other at night was the closest thing I’d experienced to the old rep system, and I loved it.

Daniel Mays stars in Code 404. Read more about the Royal Court.

‘They can’t have made any money – but that wasn’t the point’

Rosalie Craig: The value of a theatre often goes beyond its more noticeable outward facing features. The Donmar Warehouse’s artistic output is exceptional in its range and excellence and I’m lucky to have worked there – including in Josie Rourke’s Olivier award-winning production of City of Angels and James Graham’s The Vote. Yet it was as a nervous first-time mother that I really felt the depth of its human importance. Fellow new mum Michelle Terry (now artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe) and I, with our newborn daughters, were given space to collaborate on a show (Becoming) about our experiences of giving birth. It felt safe, inclusive and important. I can’t think they made any money from it, but that wasn’t the point. It often isn’t with theatre.

Rosalie Craig starred in the Donmar’s City of Angels. Read more about the Donmar Warehouse.

‘Audiences met up, excited about what they’d experienced’

Amanda Huxtable: The Lawrence Batley theatre is another building named after a dear departed white man. He passed away in my lifetime and I understand from his end-of-life carers, who are black, that he was a nice man. That’s always good to know. These things matter when you’re a black healthcare worker. He left a significant gift to our town of Huddersfield, ensuring his legacy lived on in our local theatre, now known simply as the LBT. Built on the foundations of a Wesleyan Methodist chapel, it is perhaps the most fitting of town-centre spaces. A place where calls for the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade would have surely rung out. Years later, I found myself as a young black artist in my local theatre. I have taken up the opportunities, when they came, to run workshops, direct and produce work and serve on the board. Memories flash back of theatre work presented over the years. Somebody’s Son written by Marcia Layne, produced by us; black British and bold. National touring work from Tiata Fahodzi and Strictly Arts. Meeting the audiences of Huddersfield and the surrounding areas in the courtyard, excited about what we had just experienced together.

Amanda Huxtable is the artistic director and CEO of Eclipse Theatre. Read more about Lawrence Batley theatre.

‘My home away from home’

Evan Placey: I remember wandering around backstage in my pyjamas, past the artistic director’s office and the rehearsal rooms, thinking, “This should feel weird” but it felt right. I was staying in one of Birmingham Rep’s on-site flats. The Rep has always felt my home away from home and so it was perfectly normal that it had become my literal home. It’s a community theatre in the truest sense of the word. Most people don’t sleep there but everyone has a place there. The seamless transition between public library to theatre to cafe means it’s unclear where one finishes and the next begins.

I love that their youth work is programmed in the main house alongside the rest of their programme. I love that groups of young people, of old people, of every language, just come and hang out. They feel it’s theirs. I took my mum to see a play there and lost her; she’d wandered into the library, found a book, and got comfy. My son went for the first time last year – he took home some of the Scarecrow’s straw. It’s still on his wall. A reminder that he, too, has a home away from home.

Evan Placey has been working with a group of young activists on artistic responses to the climate crisis for the Almeida’s Shifting Tides festival. Read more about Birmingham Rep.

‘A sense of experimentation’

Luca Silvestrini: In 2004, we were in Ipswich for research and development that led to our show Big Sale. We were asked by DanceEast to take part in a photo shoot for the local paper at what was to become its new venue, located at the side of the marina, among industrial sites. It was difficult to imagine how this unlikely setting could be home to a dance house one day. I remember the dancers leaping against the backdrop of an imaginary new building. Strange though it seemed, we were part of a vision. The building became Jerwood DanceHouse, now one of the UK’s most important centres for dance. I love returning there, as we’ve done so many times over the years, to create and perform shows. It’s great to see the friendly smiles of the receptionists as you walk in, the dance studios are beautiful and spacious, but most of all I love the sense of experimentation that feels possible.

Luca Silvestrini is Protein’s artistic director. Read more about Jerwood DanceHouse – DanceEast.

‘I went up on stage and spotted dancers in the wings’

Nessah Muthy: Growing up, theatre existed one day a year for me: 27 December, my nan’s birthday. Pantomime day. Epsom Playhouse put on an extraordinary pantomime. The care, the joy, the dancing, the singing, the costumes, the laughter rippling through the auditorium. I loved the plunging darkness that hides you for a heartbeat until the light glitters. I loved the cast getting the audience on their feet for one last boogie. Grandad would scramble to get in the ice-cream queue. Pantomime ice-cream is the best.

Nan would try to book seats that meant I had a chance of being selected to go on stage. I remember being up there with a Buttons or similar, spotting sequinned dancers, waiting in the wings. That’s where I want to be, I thought. Nan’s too poorly to go these days, but I take my daughters and husband, who was joyfully rinsed by the dame (with encouragement from me) last year. As a working-class kid, pantomime was my early – and only – access point into live theatre. It is one of the few theatrical spaces where working-class communities can come together and feel truly welcomed in. Thank you, Epsom Playhouse.

Nessah Muthy’s plays include The Last Clap for Kali Theatre’s Solos series. Read more about Epsom Playhouse.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News