I thought I was being ‘blacklisted’ by university colleagues, so I demanded to see their emails

Blacklisting at work has been illegal in the UK since 2010, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. It just happens informally. I know, because it happened to me.

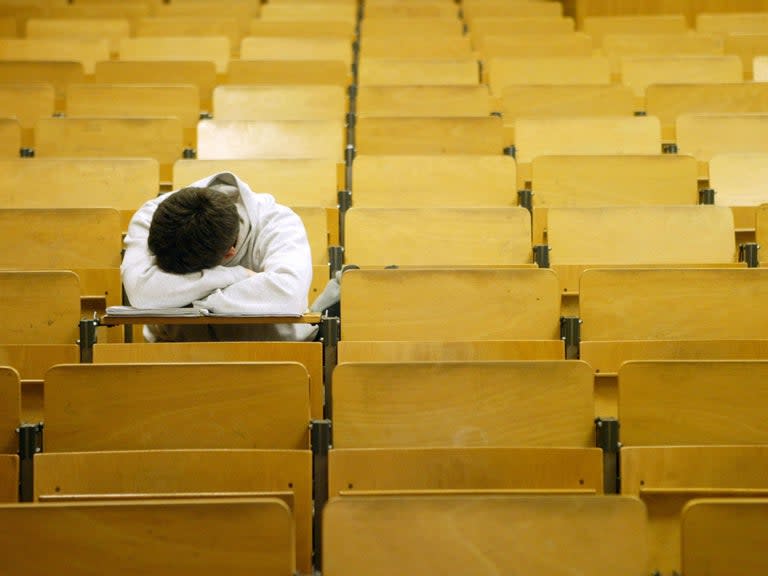

I was a recent PhD graduate at the time, and as far as I can tell, academic ‘blacklisting’ plays out in similar ways to the regular kind. When it happens, you generally know something is wrong, although you probably won’t know what, at least to start with. You will apply for hundreds of jobs, but rarely, if ever, be shortlisted. You will account for some of this by blaming bad luck. You’ll tell yourself it’s a numbers game, or the economy is bad, or there are too many applicants chasing too few jobs.

You stay optimistic. A sunny disposition always helps, no one likes a negative person, so when you go to an event and people you know ignore you, you’ll tell yourself they’re just having a bad day. You will assume that your exclusion from a conference on a subject in which you are a recognised specialist was simply an unfortunate oversight. When someone is organising a project and is interested in you initially but suddenly ghosts you, you’ll think they changed their mind, or the project was cancelled.

After a while, though, all these excuses start to wear a bit thin. A pattern emerges, of you being shut out. You are ostracised and isolated. You muddle through, teaching on fixed-term, part-time, zero-hours contracts, a low-paid disposable commodity, writing papers, chapters and articles in what little spare time you have, and believing what you’ve been told, that success is based on merit, that talent is the most important thing, and that if you work hard and hang in there you’ll get there in the end.

Except you don’t, and eventually you realise that you never will.

You start wondering what went wrong. How was your career derailed before it really began? What’s wrong with you? You know your research is good, and your publications get a fair bit of attention. Your students do well and speak highly of you. You are on good terms with your peers. So why are you excluded from your profession?

You question yourself, you second-guess your own abilities. You feel yourself becoming paranoid. You have suspicions, but no way of proving them. If you think about it too much, you’ll drive yourself mad. Blacklisting has terrible consequences for those affected by it.

I couldn’t stop thinking about what had been happening. I suppose I’m just one of those people that likes picking scabs.

There are new EU-wide data regulations, known as the GDPR, that were introduced in 2018. These regulations allow people to make a data request, called a Subject Access Request, to any institution that holds any data on them. The definition of data is pretty broad, and I was able to ask my PhD college, and several other institutions, to see all emails in which my name appeared in either the subject line or the body of the email.

In amongst the mostly innocuous material that my request generated, there were two interesting finds. Firstly, my eminent and influential PhD supervisor had let it be widely known that they thought I was an unpleasant person, impossible to work with, fundamentally stupid, and that I definitely shouldn’t be doing a doctorate.

They complained vigorously about having such an awful student, but never mentioned the two hour-long interviews they conducted with me before agreeing to take me on. After that, one of my PhD examiners had been asked about me off the record, and had advised against me. They repeatedly used insults and demeaning adjectives to block me from several employment positions and speaking engagements.

I approached the individuals and the institutions concerned about the content of my Subject Access Request. They all refused to discuss the matter with me, so I can only speculate as to what was going on. If my conduct had been that awful, I would have received a warning or been subject to some kind of disciplinary procedure, but I wasn’t, so where my supervisor thought I was difficult, it is equally possible that, as a mature student, I merely had clear boundaries. Where my personality was called into question perhaps my working-class background, my northern accent, and my Aspergers could be a reasonable explanation.

My work may well have been sub-par, but my other supervisor didn’t think so at the time, and I progressed through the doctoral process in a timely fashion, easily passing all the exams I needed to. After I graduated my thesis became a book that is now taught on masters courses worldwide. My examiner’s conduct, meanwhile, is baffling. Was it motivated by professional jealousy? A personality clash? An attempt to ingratiate themselves with my supervisor? Who knows.

There is no requirement for members of the academic community to like their students. In fact, it’s perfectly acceptable to not like your students. What is not acceptable is to treat your students with malice, and perfidy, and cruelty. I don’t pretend to be perfect. I am human, and I am as flawed as everyone else, but no one deserves to be treated badly, and that is particularly the case if the person meting out the ill treatment is in a position of authority.

As far as blacklisting goes, it is a sad, career-destroying fact that a lie is half way round the world before the truth has got its shoes on, and a good official reference is no match for insider gossip. If these senior academics were making these damaging, unprofessional, ad hominem remarks about their student in emails, what were they saying on the phone, or over coffee?

I don’t believe I was singled out for uniquely awful treatment, either. My tormentors’ conduct seemed routine and familiar to all concerned. If my experience is as common as I think, it suggests there is a far bigger problem in British universities than my regrettable post-doctoral experience.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News