Being Everywoman Is Katie Porter's Superpower

When Representative Katie Porter’s face appears on my laptop screen, backdropped by the marigold walls of her kitchen, I can instantly tell she’s having a day. She’s overwhelmed, weary, pulsating with the frantic energy of a person doing too much. It’s April 9, or day 21 since Porter more or less locked herself inside like much of the rest of the country, and yes, we are Zooming. Never in my wildest dreams did I think I’d speak with a member of Congress while unshowered, makeup-free, and in sweatpants, but here we are. And for a moment, we are not reporter and politician, but two women who find themselves in the middle of an unprecedented global pandemic, and one of us clearly needs a minute.

Like many, Porter is exhausted from all the digital demands. “One’s a call, one’s a Zoom, one requires me to be dressed up, another might require me to, God forbid, have my hair done.…” And frankly, she’s a bit miffed with staffers who schedule back-to-back meetings, failing to recognize that even Porter—a woman whose colleagues call her a superwoman, who has made drowsy congressional hearings must-see TV, and who so expertly spars with witnesses that you can almost see them quiver—also needs a break to pee sometimes.

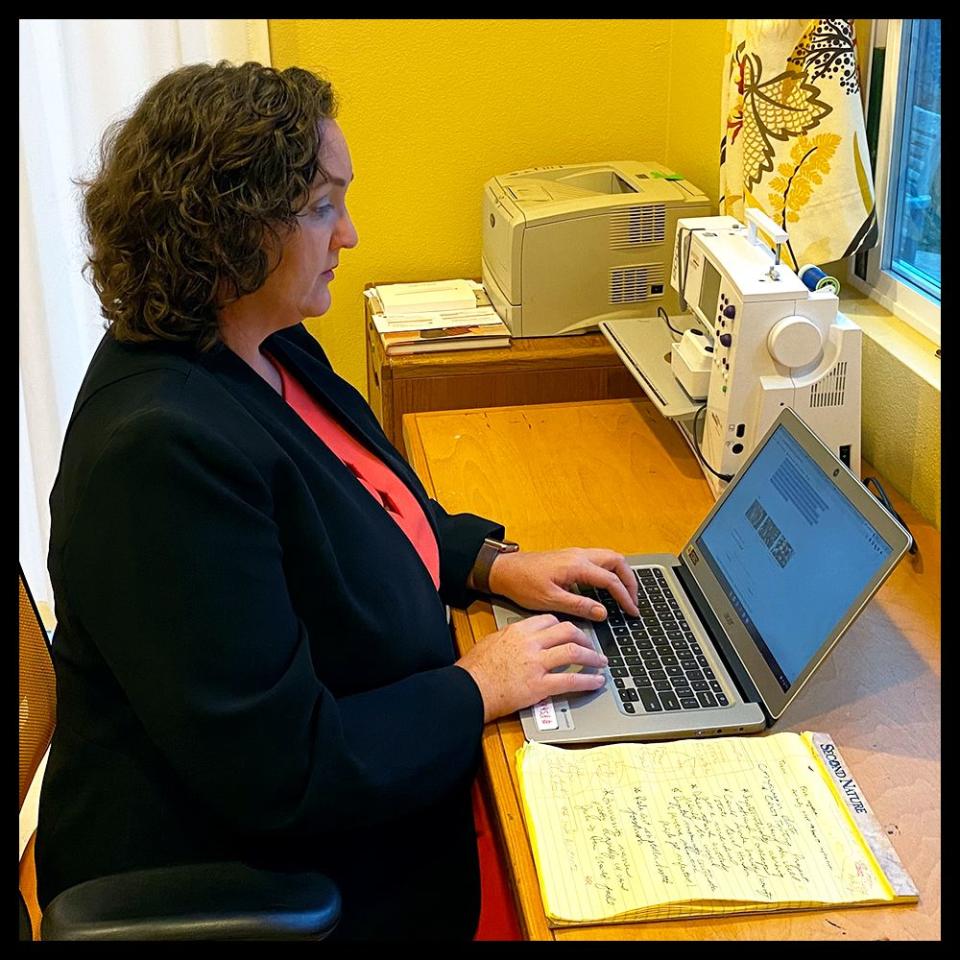

As she pulls on an Elizabeth Warren presidential campaign hoodie (“I hope Joe’s hoodies are as cozy as this is”) and pops in AirPods to drown out her children, she begins to sound like the Porter I’ve come to know from YouTube. She illustrates how COVID-19 has magnified existing workplace inequalities as only she could: by relying on props. “There are all these little assumptions,” says Porter, 46. “Like, ‘Well, just print it.’” She has a printer; it’s 14 years old. “I’m happy to show it to you,” she says, angling her camera so I can see it: a bland gray box, like the one those guys beat the shit out of in Office Space. “Do you see it? It was a gift. When my son was born, my mother gave it to me.” Her colleagues say, “Could you adjust your monitor?” “No, I can’t,” she deadpans. “I don’t have a desktop computer. I don’t have space for one. I’ve got three kids in California. We don’t have extra rooms full of shit.” They say, “How’s your home office set up?” “It’s my kitchen, okay?!” she says, giving me a tour.

The room is not flashy or slick; there’s no island or subway tile. Instead, it looks very much like the kitchen of any average American household: food items strewn about, dishes in the sink, and one overworked woman—the only single mom of young children in Congress—trying to hold it together. “For anybody with kids, their work level shot through the roof during this pandemic,” Porter says. “Some people are sitting around watching videos. I haven’t turned my TV on.” She mentions a colleague who failed to reply to a question on her last call. “He couldn’t answer because he was riding his Peloton and had to get off because he was out of breath,” she says of the $2,000-plus exercise bike, with a pointed stare. “I’m like, No words, right?”

“Look,” she continues. “I’m acutely aware I’m nowhere near the bottom, but there’s a little bit of difference between my situation and the typical Congress member’s, or, let’s face it, a lot of difference. I didn’t get elected because I’m rich and able to self-fund. I haven’t been in office for 20 years. And I’m about 15 years younger than the average member. All those things make me more attuned to the inequality of the universe. I’m at least aware, as I put on my shoes every day, that they are not like everyone else’s.”

“I just want to scream at people like, ‘My life does not look like yours!’”

And with that, Porter is ready to move on. “Thank you for letting me vent,” she says. “I feel much better.”

In late January, one of the first confirmed cases of coronavirus in the U.S. was reported in Porter’s district: south-central Orange County, a Republican stronghold that, until Porter, had never elected a Democrat. She wrote to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to request a briefing and put together a list of frequently asked questions for constituents. “We recognized instantly that the biggest shortage—more than TP, more than ventilators—was going to be accurate and trustworthy information,” she says.

When Congress began hosting regular briefings in early February, Porter says, they were “extremely poorly attended.” Over time, the numbers swelled, and by March 12, when CDC director Robert Redfield, MD, testifies before the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, the room is overflowing. “Everybody was like, ‘This is outrageous! We couldn’t even get a room that was big enough. Who planned this?’” Porter says. “And I wanted to say, ‘Where were you in February? Because the reason it’s in this small room is that’s who’s been showing up.’”

When Redfield takes his seat, Porter is ready. The week before, she had sent a letter to his boss, Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) Alex Azar, urging him to take action to ensure COVID tests were affordable and accessible, but hadn’t received a reply. The former law professor spied an opportunity. “Even if we had gotten a response to that letter, it would have been full of mumbo jumbo,” Porter says. “We really worked hard to get an actual answer.”

As her five minutes commences, she pulls out a small whiteboard and begins quizzing Robert Kadlec, MD, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at HHS, about the out-of-pocket costs, without insurance, of the tests to determine if a person has COVID-19 and an ER visit to care for someone with such symptoms. “This is like The Price Is Right,” she says as Kadlec repeatedly guesses too high. She could have just told him that she’d crunched the numbers and found the total was $1,331, but subtly shaming witnesses for not having done their homework is one of her signature moves.

Eventually, she makes her point: “Fear of these costs is going to keep people from being tested, from getting the care they need, and from keeping their communities safe,” she says, rattling off the statistics that 40 percent of Americans can’t afford even a $400 unexpected expense and that 33 percent put off medical treatment last year. Then she shifts her laser-like focus to Redfield, asking him if he will guarantee free tests for all Americans. He starts to reply: “Well, I can say that we’re going to do everything to make sure everybody can get the care they need.…” Porter cuts him off: “Nope. Not good enough.” They go back and forth like this for a bit, with Porter insisting on a simple yes or no. Instead, Redfield says, “What I was trying to say is that CDC is working with HHS now to see how we operationalize that.…”

Here's a thing you need to know about Porter: She really hates words like operationalize. Her office has a policy that all communications to the public be at an eighth-grade level, and she has explicitly banned her least favorite word, impacted. “People are not impacted by the pandemic, okay?” Porter tells me. “They are sickened, they are laid off, they are hurt, they are scared, whatever. Impacting is what meteorites do when they land on a planet.”

So by now, Porter is not mad, but disappointed, and as everyone knows, that’s worse. Not only has Redfield dodged her question, he has dared to use mumbo jumbo in her presence. She looks him in the eye and says, in that guilt-inducing tone every mom has mastered, “Dr. Redfield, I hope that that answer weighs heavily on you, because it is going to weigh very heavily on me and on every American family.” It works; Redfield relents—you can almost see him thinking, “Fiiiiine, I’ll give you what you want”—as he says, “I think you’re an excellent questioner, so my answer is yes.” Porter seizes the moment: “Excellent!” she says triumphantly, reiterating the point to make sure everyone in America has heard they are eligible for free testing.

They had. The clip shot around the internet, casting Porter as an early hero of the COVID crisis: “I’m Representative Katie Porter’s Whiteboard, and My Girl and I Are About to Kick Your Ass,” a headline on McSweeney’s read. It helped her raise money for her reelection, too—she brought in more than $2 million in the first quarter of 2020, more than any House member in a battleground district.

Porter has watched her exchange with Redfield a couple of times, and that part at the end where she makes sure she’s been heard is what stands out to her most. “Hearings are not conversations between two people in power,” she says. “The audience is the American people.” Every congressperson would claim to understand that, but Porter is one of few who actually demonstrate it. Her colleagues pontificate; she instructs, with graphs and poster board, if necessary.

“The most important thing about Katie is that she has this superpower, which allows her to do a searing cross-examination and get the jewel,” says Linda Lipsen, CEO of the American Association for Justice, a lobbying organization for trial lawyers. “It takes experienced trial lawyers days sometimes to do that, and she can do it in five minutes.”

But the key to her appeal is not just that she is a skilled questioner; it’s that when she is skewering JPMorgan Chase CEO and chairman of the board Jamie Dimon, HUD Secretary Ben Carson, or Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, she isn’t just speaking to the American people—she is speaking for us. Porter is our collective rage personified. And damn, if it doesn’t feel good to see her make witnesses squirm.

When Porter and I Zoom for the second time a day later, it’s 9:15 a.m. in California, and she’s still making breakfast for her kids. She had early calls this morning, so the meal is delayed, and she’s behind on answering emails. “The hard thing about living on the West Coast is that nobody cares about you,” Porter says. “They start sending you emails at, like, 8:30 a.m., asking you why you haven’t responded.” (And no, her tardiness is not caused by less pressing things: “I’m not baking any bread, people,” she says.)

It’s fitting to be interviewing the viral hit maker via video. After all, that is how America got to know Porter. She shot to public consciousness in late February 2019—nearly two months after she was sworn in to Congress on her forty-fifth birthday—when clips of her asking Mark Begor, the CEO of Equifax, if he would be willing to share his Social Security number, birth date, and address at a hearing began making the rounds online. When he declined, Porter used his reply to point out the hypocrisy of the company’s argument that consumers weren’t hurt by the data breach—one of the largest in history, which exposed the personal information of as many as 143 million people, or about half the country. Headlines like “Watch a Congresswoman Destroy Equifax CEO Mark Begor in an Epic Privacy Burn” followed.

Porter did it again two weeks later, when Wells Fargo CEO Tim Sloan testified about the bank’s consumer abuse scandal in 2016. She used her now-famous props to show how the company’s official response contradicted what Sloan had told the committee. He resigned two weeks later. By April, when it was Dimon’s turn in the hot seat, it was understood that eviscerating witnesses is just what Porter does.

Her colleague Ayanna Pressley (D–Mass.), a fellow freshman, says Porter’s communication skills stood out to her from the start. “My first impression was that she was Superwoman,” Pressley says of meeting Porter at orientation. “She could speak about very complicated things and make them digestible and interesting.”

This is how she does it: Porter starts by asking, “What is the problem we’re trying to solve?” She games it out with her staff, anticipating how a witness may respond and plotting how to react in order to steer the conversation toward her end goal. Still, nothing can fully prepare Porter for when it’s her time to shine. “Whenever I hear them say, ‘The gentlelady from California is now recognized,’ my heart kind of stops,” she says.

While some members drone on without ever really making a point, Porter feels pressure to make each second count. “I definitely get nervous, because I know it’s my one shot.” During questioning, she doesn’t see or hear anyone else in the room. “I’ve often wondered, ‘What are the other witnesses doing? How are they reacting?’ I don’t know,” Porter says. And she also has no clue how she performed, even when she nails it. “When I’m walking out, I’ll ask my staff, ‘How do you think it went?,’ and they’ll be like, ‘Oh my God, it’s already blowing up.’ And I’m like, ‘It is?!’”

But going viral isn’t just Porter’s way of speaking to the public; it is also how she found her place in a 535-member body where it’s tough for anyone, let alone a lowly freshman, to stand out.

About a month into Porter’s tenure, Senator Elizabeth Warren, her former law school professor and mentor, called to see how she was doing. “I said, ‘Okay, I guess. Not that great,’” Porter recalls. It was a stressful time in Washington: The government was shut down, and all the negotiations were happening at higher levels. “I said to Elizabeth, ‘I don’t feel like I’ve found out how to make a difference.’”

About a month later, after Porter’s star turns with the Equifax and Wells Fargo CEOs, Warren called again. “She said, ‘You found your voice. Don’t ever stop using it,’” Porter says.

“I love the way Katie approaches hearings,” Warren tells me. “It isn’t gratuitous. She never goes for the cheap shot. She never gets flustered. But she knows who she is there to fight for, and the people she’s fighting for need someone on their side.”

There’s a reason Porter cares so much about making members of the public feel heard. As a kid growing up outside Lorimor, Iowa (2020 population estimate: 352), during the 1980s farm crisis—which, at the time, was the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression—Porter remembers a chasm between politicians on TV saying, “We care about farmers,” and the devastation she saw all around her: families losing farms, people committing suicide. “So many politicians would come to my tiny town—they’d be at the Lions Club or the Pizza Ranch—but when we got in really bad trouble, nobody came, nobody talked to us,” she says. “They want your vote, but then, when you need them, they’re not there.”

“Believe it or not,” Porter says, it was an internship in Senator Chuck Grassley’s office, the state’s long-serving Republican senator, during college that taught her about the type of legislator she wanted to be. “He had a policy of writing back to every single constituent and doing what they call the Full Grassley, which is visiting all 99 counties in Iowa every year,” she says. “Those things made a big impression on me about how important it is to listen.” As of May 31, Porter’s office had received 123,000 letters, emails, and calls from constituents, and had responded to 93 percent. During the pandemic, her staffers started calling constituents more often; Porter has been calling them as well. “I want to make these calls,” she says. “I want to hear these voices.”

But the truth is, Porter doesn’t need to take calls to know what ordinary people are going through. She doesn’t rely on staffers to tell her what it’s like out there with the general public; she’s at the grocery store with them. When she was sick with COVID-like symptoms in March, she was scared, thinking about what would happen to her kids if she died (“A particularly unique fear among single parents,” she says). And when she heard about reports of domestic violence during the pandemic, she felt that, too. “A lot of the worst things that happened in my marriage happened because of the acute stress of the divorce and life changes,” she says. “That’s not unlike the stresses that some people are facing now with COVID.”

She now has custody of her and her ex-husband’s three children: Luke, 14; Paul, 12; and Betsy, 8, who is named after Warren. “Katie understands deep down what it’s like to do your best and get caught up in a bigger wave that knocks you over,” Warren says. “She’s resilient—she bounces back, but she never forgets what it was like to be down.”

That understanding, that memory, that daily reality of being the one in charge of getting three other humans through the day, and the exhaustion that comes with it, is also what makes her relatable. “When she says, ‘My hair is frizzy, the kids are hungry, and dinner is burning,’ everyone understands that,” Pressley says. “Yes, she is brilliant, smart, extraordinary, and accomplished, but you can see yourself in her. She is everywoman.”

Sure, Porter may have attended the prestigious Phillips Academy Andover, Yale University, and Harvard Law, but she didn’t start out that way. She and her three siblings grew up in a two-bedroom, one-bathroom house built by her great-grandfather. Her father was a third-generation farmer; her mom hosted the public-access show Love of Quilting. In a town so small there were only 13 people in her grade in elementary school, she was an outlier when she applied to Andover. “It was very risky,” she says. “No one had ever heard of that.” But she wanted more from her education. “I mean, my sixth-grade textbook said, ‘One day man may reach the moon,’” she says.

Her first night at Andover, she traded stories with her roommate, who came from Naples, Florida, one of the wealthiest cities in the country. “I don’t think she was trying to make me feel bad,” says Porter, who attended on scholarship. “But she was saying, ‘Our town has all these beautiful flowers and plants in the medians of the highways,’ and I was like, ‘My road is gravel, and it was a big deal when the gravel wasn’t dirt.’ That was an upgrade.”

Arriving in Washington gave her that same “poor church mouse” feeling, she says. “People ask, ‘Do your kids go to public or private school?,’ and I’m like, ‘We make the exact same salary and I have three kids—just do the math,” she says of the $174,000 salary that members of Congress earn. “You might as well ask me if I drive a Ferrari.”

She calls it a well-meaning question, but says it comes from the assumption that members of Congress share a set of privileges. “There’s a certain model of being a congressperson that I resist,” Porter says. “There are people who think the bicoastal thing is cool—they have a penthouse here and a mansion there. And then there’s my first apartment in DC: I had no closet, no cable, no Wi-Fi—just a mattress on the floor.”

What it boils down to is this: “There is a class divide in Congress,” Porter says. She gives an example of how she and three of her colleagues all own the same dress from Macy’s. “They’re Calvin Klein. They’re like $99. That’s what we have.” When Speaker Nancy Pelosi made headlines in 2018 for a photo that showed her looking like a badass, strutting out of shutdown negotiations at the White House in a Max Mara coat, Porter was blown away—but not for the reason most people were. “I love that photo, but it wasn’t lost on me that that turns out to be a $3,000 coat,” Porter says. “Never in my life will I own a $3,000 coat. [Pelosi] said she wore it that day because it was clean. Well, all my laundry could be done, and there wouldn’t be any item in my closet that costs more than a couple hundred dollars.”

She felt the divide on the campaign trail, too. Her now-colleague Representative Gil Cisneros, a Democrat from the district north of hers who was also elected in 2018, won a $266 Mega Millions jackpot in 2010 and spent $9 million of the winnings on his campaign. “That’s a really different experience than I had, where I remember just crying because I didn’t want to ask my friends for more money because I just didn’t know if they had it,” Porter says.

At first, she tried to look the part of a fancy lady running for Congress after a staffer told her that pulling her hair back in a ponytail every day wouldn’t get her elected. He sent her for a haircut, and “I came out looking like Nancy Pelosi,” Porter says. “It was just impossible. I have really curly hair, and I do not get a blowout every day at the Four Seasons or whatever.” She would spend precious time trying to tame unruly strands, thinking, “Do you have to have straight hair to help the American people?”

She hired a new campaign manager, Erica Kwiatkowski, who got it. When she found out Porter loathed straightening her hair, “we went to the salon and chopped it all off, and that took 30 minutes off her day,” Kwiatkowski says. It was one of many adjustments from the norm they made together to compensate for Porter being a different kind of candidate. “She is relentlessly who she is, and she is not going to change, nor should she, for this world,” Kwiatkowski adds.

And who is Porter? A middle-class mom who dresses like Batgirl when she votes on an impeachment inquiry because it also happens to be Halloween. A former Cub Scout leader who goes on Showtime’s Desus & Mero and complains about “bitches” who make fun of her minivan. A congresswoman who wants to start a “straight shooter” caucus for members who tell it like it is. “You have to be scrappy—as a working mom, a single mom, and as someone who doesn’t have wealth and all these advantages. You have to fight to be taken seriously,” she says. “That is even true in Congress, and I wasn’t prepared for it.”

During our third Zoom call, Porter quite literally stumbles on a prop of sorts that inadvertently helps make her case. She’s speaking to me from her yard, and at one point stops abruptly. “Hang on. You’re going to love this…I stepped in dog poo,” she says, taking off one green Converse and flashing it to the camera. “I just think there are a lot of my colleagues who would never admit that they ever—in their whole life—stepped in dog poo. And it’s like, Who hasn’t? I don’t think we get anywhere trying to separate ourselves from the American people.”

Photography by Amy Harrity; Hair and makeup by Nicole Chew for Oribe and Chanel; Production by Sameet Sharma.

This article appears in the August digital issue of ELLE available on Apple News+.

You Might Also Like

Yahoo News

Yahoo News