I took part in the government’s coronavirus antibody test trial – this is what I learnt

I wait in silence, staring at the test, willing the extra line to appear – the line that means I’ve already had coronavirus.

It’s similar yet different to the other time that, as a woman, I’ve stared at a stick with some of my bodily fluids on it, waiting to see if another line will appear. Similar, in that the nervous anticipation feels familiar. Different, in that this time I actually do want to see that second mark gradually become visible.

I’m in the unusual position of having my very own at-home Covid-19 antibody testing kit, provided by Imperial College London and Ipsos Mori as part of a study they’re conducting on behalf of the government’s Department of Health and Social Care. I signed up for an app where participants reported coronavirus symptoms way back in the early days of the pandemic, and have been selected at random to take part in an experiment to see how many people in UK might have already carried and fought off the virus.

The literature that gets sent with the testing kit is at pains to communicate that the result is not, repeat NOT, to be taken as gospel on an individual level – that the data is only useful when looked at en masse. I presume this is so those who test positive for antibodies don’t start sneezing on strangers in the street and deliberately putting their masks on back to front, but who can say.

I have been completely convinced I had the dreaded C word back in March, a couple of weeks prior to lockdown. The symptoms were so strange, and so unlike anything I’d ever experienced before, that I actually thought I might be pregnant: a deep, bone-weary fatigue that left me unable to get out of bed; nausea without being sick; alternating between fevers and chills. And now here I am, four months later, having come full circle and preparing to take the other kind of test.

I feel nervous, in part, because I felt like I spent most of lockdown wearing a secret invincibility cloak. I followed the rules to the letter, staying away from people, washing, sanitising, masking – I was never cavalier about it – but I wasn’t scared because, deep down, I thought the virus couldn’t get me. I had already had it, so I was safe.

Now, there was going to be some indication – if not irrefutable proof – of whether or not my psychological comfort blanket had been complete nonsense.

The kit came in the post and sat on the coffee table for three days while I continued to bask in the unknown – that I possibly, probably, definitely had already had it. But on day four I decided the time had come to step up and find out the truth.

It was all very straightforward; the kit came with everything you’d need and the pamphlet had helpful diagrams and a big font to ensure you’d have to work damn hard to mess it up. First came the alcohol wipe to clean your finger tip (they recommend doing it on your non-dominant hand – so, for me, my left index finger). Then the lancet, designed to prick the skin – you twist off the cap, press the uncapped end against the fleshy part of your chosen finger, and push it down until you hear a click and feel a tiny pinch. Next comes the only vaguely gross bit if you happen to be squeamish, which I am: you’re encouraged to squeeze your finger tip to “form a large droplet of blood”. Shudder.

Here’s one tip – if you find yourself taking the at-home test, don’t bother faffing around with the miniature pipette that comes with the kit, which you can use to collect the blood “if you prefer”. It doesn’t really work and makes things even messier – far better to just turn your finger over and let the droplet splatter unceremoniously into the appropriate box on the test. And don’t be shy – it needs to be covered. The test doesn’t work if you don’t deposit enough blood, apparently.

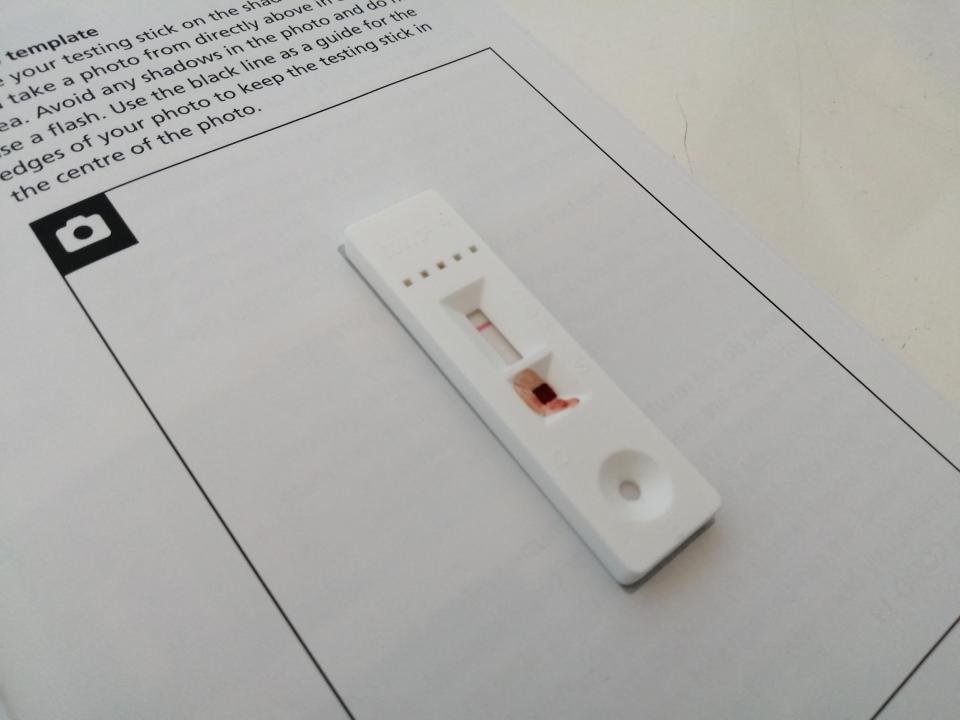

There’s just one more step to go – adding a couple of drops of “buffer liquid”, whatever that may be, to a circular well at the bottom of the test stick – before the waiting game begins. Ten minutes on the clock. There’s nothing to do but sit and stare.

The first thing of any note to happen is the control line’s transition from blue to red after a minute or so. Don’t get excited – that just means the test is working properly. What you’re waiting for is one or two more lines to appear. The test checks for two types of antibodies: IgM, which are fleeting and don’t stick around much after you’ve had Covid, and IgG, which develop in most patients at around two weeks after infection and last in the body for longer (although for exactly how long remains unknown). I had no chance of the former, but high hopes for the latter.

It wasn’t to be. After 10 minutes I have my answer: nada. No extra lines for me. In one fell swoop, all my cocksure convictions and invincibility cloaks are stripped away.

Trying to hold onto the small consolation offered by the millionth variant of “the antibody test is not reliable at an individual level” printed in the pamphlet, I line up my test with the shaded area on the designated page and take a photo of it from above as requested. Logging on to the website provided, I then proceed to upload the picture and fill in an extensive questionnaire about my habits during lockdown (did I go shopping? Go outside? Wash my hands?) and any symptoms I had when I thought I’d been infected.

I fill it in mechanically, thinking how euphoric I’d feel if I had tested positive. But I shouldn’t have been – according to the NHS, testing positive for antibodies “does not tell you: if you’re immune to coronavirus; if you can or cannot spread the virus to other people.” There’s still so much about Covid-19 that we simply don’t know.

In any case, it turns out I may have had it. They weren’t wrong about the test being “unreliable”: a little research tells me that in up to 20 per cent of people who’ve had Covid-19, the test will not be able to detect antibodies in their blood (the false positive rate is much lower at less than 1 per cent). I could have had a false negative. Or I could have had coronavirus but not produced antibodies against it. Or I might never have had it at all. I suppose I’ll never know. But at least it allowed me to live free from fear for the last four months. And that in itself is something to be thankful for.

Read more

Yahoo News

Yahoo News