How Troy Perry, Metropolitan Community Church Founder, Made LGBTQ History—With God’s Help

Of course Reverend Troy Perry is a preacher. He sounds like one. His voice booms smoothly. His Southern accent remains in place, despite years of Californian living. More than one sentence ends with a “And I will tell you…”

On July 27th, Perry will celebrate his 80th birthday, and there’s a long, dramatic life to look back on which at its heart is about how one gay man who cherished his belief and faith in God did not believe—as he was constantly told—that God did not love him because he was gay. And to prove it, he created a church all of his own.

One Troy Perry story or adventure tumbles into another: leaving home as a teenager to escape an abusive stepfather, founding the global, LGBTQ-inclusive Metropolitan Community Church in 1968 after recovering from an attempt to end his own life, meeting his husband Phillip Ray De Blieck in a leather bar—and suing the Los Angeles Police Department to hold the city’s first Pride parade in 1970, then called Christopher Street West.

In 1970, Perry’s friend Morris Kight, a gay activist, called him and asked if he and their friend Reverend Bob Humphries could come over. They always put “Brother” before their names: Brother Morris, Brother Bob, Brother Troy and so on. Kight had received a letter from a GLF member in New York City who wondered if they might hold a march there to mark the first anniversary of the Stonewall Riots.

In 1970, four American cities would hold such marches—New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and San Francisco—as The Daily Beast reported in a recent article. In that article activist Karla Jay recalled the 1,168-strong demonstration in Los Angeles, and Perry’s arrest.

They Marched in America’s First Pride Demonstrations in 1970. They’re Still Out, Loud, and Proud.

In 1969, Perry had already led a small march calling for an end to anti-sodomy laws, and in 1970 a protest over the death of a male nurse, Howard Efland, at the hands of police after a Vice Squad raid at a Los Angeles hotel where men met to have sex.

To plan the first post-Stonewall march in Los Angeles, the three “brothers” met at Perry’s home, which they nicknamed the Old Parsonage. Kight said, “So, Brother Troy, we’re going to hold a demonstration.”

Perry recalled that he replied, “Morris, wait a minute. We already hold demonstrations. This is Hollywood. Why don’t we hold a parade?”

The men quickly found out this would not be easy. First, they had to appear before the Los Angeles Police Commission. It was decided that Perry would ask for the march in the name of the MCC, which was a nonprofit. The paperwork was duly filled out, and then the Police Commission asked the men to come to a hearing.

When they arrived, recalled Perry, the extremely homophobic then-chief of police, Edward M. Davis, was there. Kight, Perry and Humphries had agreed not to use the word “homosexual,” to see if they could get the march passed just using the MCC’s name.

Perry recalled saying, “That’s fine, but if they start on me, I’m not going to take any nonsense from the Police Commission. I don’t care.”

Perry paused. “Well, they started on me. They browbeat me for hour. They kept saying, ‘Who do you represent?’ Finally, I said, ‘I represent the homosexual community of L.A.’ With that, you’d have thought I had shot them in the face. But they knew who we were, it was obvious to me by the way they asked questions. Yak, yak, yak, they carried on, ‘What do you expect to happen there?’ I told them, We are going to hold a parade.’”

This back-and-forth continued until the Commission said they would consult, and for the men to return at a particular time. Perry, Kight, and Humphries went to have lunch, where it dawned on them the meeting may have started back already, and then the cops claim that the three of them hadn’t turned up on time. The men returned 30 minutes earlier than they were due to. The meeting had indeed restarted.

The Commission called the men back in. “They laughed at us, and made fun of us,” Troy recalled. “They said that we could hold the march on the condition that we had 5,000 people marching, and that we would put down $1 million to pay businesses for the damage “once people throw rocks and bricks at you.”

Perry retorted, “Oh, like the Jews in Germany.” The cops “didn’t like that at all. Their third condition was that we put up a cash bond of $500,000 to pay the police ‘to protect all you people.’”

There was “no way” that the group could come up with that kind of money. Kight suggested they call the ACLU, whose lawyer attended the next meeting. Perry recalled ACLU lawyer Herbert E. Selwyn informing the cops, “The City Charter says we have to meet with you twice before we sue you. This is the second meeting.”

The cops, said Perry, then said they would remove one of the conditions—that the march needed 5,000 attendees. The other two financial conditions stayed in place.

The following Monday the case was in court, where “the judge banged his gavel and said something along the lines of, ‘I don’t care if you have to order out the National Guard to protect this group. They do not have to pay anything. They’re taxpayers. They don’t have to pay a bond, or put up cash for a bond.’”

The three men were overjoyed, but had only a couple of days to plan a march. They called “every LGBTQ group in California,” and Perry created a special section for people with pets. He recalled one magazine’s photograph of a young man with an Alaskan husky wearing the sign, “We don’t all walk poodles.”

Gay members of the VFW (Veterans of Foreign Wars of the U.S.) attended in uniform, carrying flags. The Gay Liberation Front float featured someone dressed as a fairy on a cross being crucified by the LAPD, while other people dressed as fairies enacted being chased by people dressed as members of the LAPD.

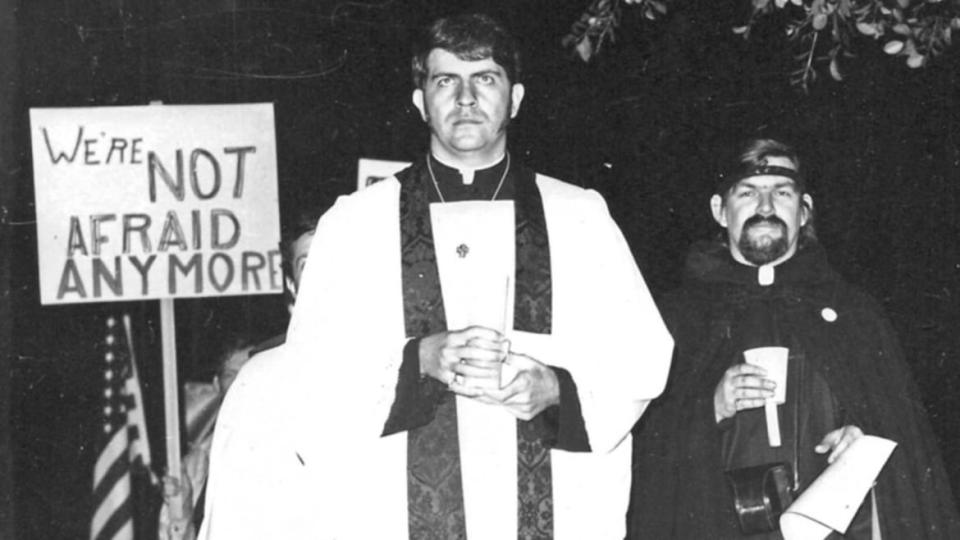

Rev. Troy Perry at the 1970 Christopher Street West parade, which he helped organize.

A group from the then-extremely conservative Orange County carried a sign reading: “Homosexuals for Ronald Reagan” (who was then the state’s governor). One woman said to Perry: “I can forgive them for being gay, but never for being for Ronald Reagan.”

“When I came around the corner and saw all those people I knew it was part of something historical like I did when I founded the church,” said Perry of that day. “We held the parade. We sued the government, and we won.”

The MCC’s choir sang in the street, and Perry—in his reverend garb—was accompanied by his then-partner and mother. “I didn’t know what to expect, I’ll be very honest,” said Perry. “But there were thousands of people on the sides watching and just over a thousand of us in the parade. It was incredible, there we were. I had never seen so many people disguised in dark shades and hats, but we proved we could do it. And no one was attacked.”

After the parade, Perry announced he would fast and pray until somebody from the city government came and talked to him. Two female activists joined him, Carole Shepherd, then-Los Angeles president of the Daughters of Bilitis, and Kelly Weiser of HELP (Homophile Effort for Legal Protection).

Perry recalls a “bad cop” telling them they would be arrested. Then a “nice cop” asked more gently what the group was doing, and said they might be arrested. Perry said if it was illegal to fast and pray, then he accepted they might be arrested.

A short time later, the cops began arresting them, and Perry asked Kight to get the other protesters out of there to avoid a bigger situation; he was worried the Fire Department would use water to disperse them. The cops told Perry that he was not going to be handcuffed, but warned him not to try to jump out of the police car. “I said, ‘If we fall out of this police car, you’re going to have problems, I want you to know that.’”

Perry declined to put up bail. He said he could carry on fasting and praying in jail. The police, he said, woke him every hour during the night to take his photograph to prove they were not beating him up. Meanwhile, outside the jail as The Daily Beast reported, Kight had beer poured over him by a fellow activist who called him a coward when he informed them that “Brother Troy” had asked that demonstrators not go to the police station.

In his cell, Perry pulled his coat up over his face as the lights were kept on all night. One inebriated person, thinking he was a Catholic priest, made a sign of the cross when he saw Perry’s ecclesiastical garb. Later, a cellmate came in. The person, who was around 5 foot 2 and was wearing lipstick and rouge, was called Peanuts and they had been beaten up, “and the police didn’t care.”

A city attorney told Perry he would stay in jail until he put up the money to leave. Perry declined. Another, cheerier attorney appeared and told Perry: “I’m glad to meet you! You’ve been arrested for human rights, I hear.” Perry replied that he had, and that he intended to stay in jail and pray and fast. The lawyer replied: “Are you joking? There’s press and a huge crowd out front.”

At court, the first person Perry saw was his mother crying, “which upset me no end. I was always worried about my mother being hurt. She was so good to me. There are photos of her with me at that first Pride. She was the first heterosexual member of the MCC when she moved out to live with me.”

When the judge entered the courtroom, Kight and the other LGBTQ activists refused to stand up. “That was the biggie in California in those days, you refused to stand. It was that era’s ‘taking the knee.’” Selwyn, Perry’s lawyer, ultimately convinced Perry to pay the $25 fine.

“I closed that book. I knew I wasn’t mentally ill.”

Perry was born and raised—in the early part of his life—in Tallahassee, Florida. He had a “wonderful” childhood until he was 11 when his father, also named Troy, a bootlegger, was killed by the police.

“I didn’t know he was a bootlegger until he was killed, and it was on the front page of the Tallahassee Democrat,” recalled Perry. “All the other kids’ at school fathers did the same thing as mine. He just had the biggest liquor outfit. He sold moonshine to poor folks and bonded liquor to the then-governor of the state of Florida. It was a dry county at that time, and it was all so hypocritical. Everything happened behind closed doors.”

Perry recalled he “had to grow up very quickly. After my father was killed, my mother (Edith) said, ‘Troy, you have to help me. You have four younger brothers. You’ve got to be a dad to them. That’s exactly what I did.”

His uncle and cousins were clergy. As a child, Perry went to a friend’s Seventh-day Adventist church on a Saturday for Sabbath school. On Sunday morning he went to a Baptist church (his mother’s church), and on a Sunday evening to a Pentecostal church (his father’s).

“I dropped out of school in the 11th grade,” Perry said. “The Pentecostal Church told me that Jesus was going to come any way, so I thought, ‘What do I need algebra for?’ I was thrown out of an uncredited Bible college with the parting words, ‘You’re not worthy to be educated by Christians.’” (When Perry joined the board of trustees of the Chicago Theological Seminary he recalled that he was “the only person never to have gone to high school.” He insists all MCC clergy complete their educations at seminary.)

Six months after his father died, Perry’s mother remarried. “She was from that generation who wanted to be at home and be a mother. He was an awful, abusive alcoholic and hated my guts,” Perry said. “My name was Troy, just like my father’s. Maybe I reminded him of my father.”

The family moved to Daytona Beach. “He beat up my mother in front of us. One day she called the sheriff. He kept calling the house from jail. My mother, of course, was typical of Southern women of that time. After three days she dropped the charges. He came back, said everything was OK, but he was looking at me in a way that I knew I had a bad problem, so I ran away from home.”

Perry was 13. He first went to his uncle’s farm in South Georgia. Perry’s aunt told him she thought God had called him to preach. The following Sunday he preached at a church for the first time: “I was very good at what I did.”

Next, Perry went to stay with an aunt in Texas. His mother kept asking him to come home, and threatened to have his Texan aunt arrested if she didn’t send him home. She had left her abusive husband. Perry was homesick, and returned to Florida. By 15, he was licensed to preach on the Southern Baptist Church.

At 18 he approached a pastor in the Pentecostal Church, and told him he was attracted to men. “He said all I needed to do was marry a good woman, so I married his daughter, Pearl. He wasn’t as flippant five years later when we divorced.”

The couple had two sons, Troy III, and Michael. Perry admitted to Pearl he had slept with a man, “but didn’t know the word ‘gay’ back then.” He had read about homosexuality in a psych book in junior high, “where it talked about us being sick, criminal, and wear our mother’s clothes. I closed that book. I knew I wasn’t mentally ill.”

At 19, Perry was excommunicated from a church in Illinois, where the couple were then living, after he admitted being gay. His bosses gave him $20 and asked him to leave the state. Then the family moved to California, where Perry worked in a plastics firm before again becoming a full-time Pentecostal pastor, the church trebling its attendance in his time there.

One day, at a bookstore, Perry asked if they had any books about homosexuality. He found a physique magazine, some fiction, and Donald Webster Cory’s The Homosexual in America. “I read that, and knew without a shadow of a doubt I was gay. Up until then, I couldn’t believe there were people like me.”

Perry hid the books at home, and talked to his Californian church boss.

“The blood drained out of his face. ‘Have you molested children?’ he asked me. ‘No, I said. ‘What makes you think you’re a homosexual?’ I told him I had read this book. He said it was ‘a trick of the devil,’ and that they would pray for God to heal me. I told him that I had prayed for that for a long time, and that God didn’t seem to hear that prayer. He told me to tear the books up. I read and re-read them. They refortified everything I felt.”

A bishop told Perry he would be excommunicated, and advised him not to mention his homosexuality as the reason, but that he had “failed the Lord.” He met his wife and children in a coffee shop, and was honest with her. She had found the books he had hidden under a mattress.

In one, she had read that some gay men had “stayed married heterosexually.” Perry said that neither of them could, or should, live that way, and that he had to find out who he really was. His wife took the boys to the live with her parents.

Perry told his older son, Troy, to help his mom with Michael. Perry recalled crying as he saw his sons leave. It would be 17 years before he would see one of them again. “I did everything to find them.” Her parents were both Pentecostal, who equated homosexuality with demonic possession.

As her presence at the 1970 Christopher Street West parade proved, Perry’s own mother was very proud of him.

“She was like every mother, she was really afraid for me,” Perry recalled. Some MCC members had been reluctant to demonstrate alongside him, as they were worried they could be attacked or murdered. Perry would reply that they were Christians, “and, as the apostle Paul says, ‘to be absent from the body is to be present with the Lord.’ Even if they murder us life eternal goes on. Mom was worried for my safety as any mother would be.”

She appeared on television programs supporting her son, and saying similar things “which rang true for other parents” of LGBTQ people.

“She lived with me for 18 years before she died,” said Perry. “Throughout my life she wanted to make sure I was OK. She asked me, ‘Why do you have to tell everybody you’re homosexual. I said, ‘Mother, everybody asks. The state of California asks teachers and trash collectors. Are they frightened I am going to rape trash cans?’ I’m not going to lie ever again.”

Perry joined the military for two years after his marriage broke down. The forms asked applicants had “homosexual tendencies,” underneath the boxes for having tuberculosis and cancer. Perry laughed. “I wasn’t going to tick a box saying I had ‘homosexual tendencies.’ I was a homosexual.”

While serving in the military, he received a letter from his wife’s lawyers, seeking a divorce and threatening to expose his sexuality to his military bosses if he didn’t agree to it. Perry did not capitulate, and the couple were divorced when he left the military.

Michael got in touch with Perry when he was a teenager. Troy has said he does not accept Perry as his father, and has asked his father never reach out to him. Perry is disappointed “in my heart of hearts” not to have a relationship with his older son, though he and Michael have built a relationship.

He told his military colleagues that he was gay, and “they just thought I was Californian,” he recalled, with a gust of laughter. Stationed in Europe, Perry was dancing with a Dutch guy in an Amsterdam gay bar when he saw two cops come in. He freaked out, until his Dutch buddy explained that they were cops just having a beer.

Other friends served in Vietnam. Some died there. “Nobody wants to go to war,” said Perry. “I supported friends in it, and ones who ran away from it. I knew GI’s in the barracks who despised the military, who hated being there. Others were more gung-ho. I was in the middle somewhere. I think that being gay means you have the empathy to understand, and see, difference.”

“I loved God so much, but I was told God couldn’t love me.”

Founding the MCC is “such an incredible legacy,” Perry said, his voice breaking. The church now has around 43,000 members within 222 congregations in 37 countries.

Around the time of the organization’s 51st anniversary in 2019, the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History asked for a collection of items from the founding of MCC.

The item that meant the most for Perry to donate was the Book of Common Prayer he used at the MCC’s first service on Oct. 6, 1968. He used it for the first same-sex wedding he performed for a young male couple in 1968, long before marriage equality became the law of the land, “and more AIDS funerals than I can ever talk about.”

Perry is extremely proud to have the Smithsonian recognize his work.

“You don’t know when you grow up in the South,” Perry began, his voice breaking, “and you have people who… when you don’t understand it, you think you are only person in the world who is gay and lesbian growing up in the ‘40s and ‘50s, and starting to have sex during the ‘40s and ‘50s.”

The first sex Perry had was when he was 9 years old with another 9-year-old boy in his neighborhood. They had sex until they were 12, when Perry left town. When Perry returned from the military, aged 29, the other boy, now also 29, found out he was visiting his aunt in Tallahassee, en route to California. They met up.

“He was so cute, he drove us into the woods in North Florida. He was in the Coastguard. We just sat there, and it was hysterical. And finally I said, ‘Well are we going to have sex or not?’ He said, ‘Oh my God, I wasn’t sure if you still thought you were homosexual.’ And I said, ‘Oh yes I do.’ He had no idea how much I knew what I was!”

So, did they have sex? Perry roared with laughter. “Yes we did!” And how was it? Another roar of laughter. “Wonderful!”

Perry’s faith was still in apparent conflict with his sexuality.

“In the 1950s, I had been persecuted for who I was by my church. I loved God so much, but I was told God couldn’t love me. I was thrown out of the ministry. I married heterosexually because my church told me it would change me. It didn’t. Through puberty, they had me singing, ‘Jesus loves me, this I know.’ Once I went through puberty, they said, ‘No he doesn’t.’ I say to young gay people today, ‘You have nothing to prove to anybody.’”

Perry set up MCC after falling in love for the first time in his life, and feeling despair after that relationship—with a young man named Benny—ended. “l cut my wrists hoping I would die. I was rushed to hospital,” Perry said. He recalls a Black woman in a nurse’s uniform coming into his room at Los Angeles County General Hospital telling him, “You’re too young for this. I tried it too.” She held out her arms, which also showed the old scars of cuts.

“I thought God couldn’t love me up to that point,” said Perry. “I broke down crying. She left the room. I prayed, saying I knew I had committed a sin, but not the sin of homosexuality—the sin of setting up my partner as God.” Suddenly, Perry felt what his church calls “the joy of our salvation.”

A “bad cop” doctor arrived, and asked Perry why he had attempted suicide, calling it “crazy.” He wanted to know if he needed to lock Perry up for 72 hours if he thought himself a danger to himself and others.

Perry asked what the doctor thought. “I think you need your ass kicked all over this hospital, but I’m not offering to make that choice for you,” the doctor said. “But you tell me. You’re in charge of your life.”

Perry said that he was going to be OK, and the hospital could release him. Perry’s roommate, Willie Smith, picked him up, and the next morning asked if he needed him to stay with him. Perry declined, and mulled having to buy a long-sleeved shirt to cover his scars.

As he lay on his bed, he remembered praying in hospital the night before and how he felt that joy. “I said, ‘God, that can’t have been you, because I’ve been told the church cannot love me.’”

Fifty-one years later, Perry said God spoke to him in response, “in that still, small voice said, ‘Troy, don’t tell me what I can and can’t do. I love you and I don’t have stepsons and daughters.’ And with that, I knew that without a shadow of a doubt I could still be a Christian and a gay person.”

Later, another realization hit Perry: if God loved him, then he had to love other gay people. “That was my revelation.”

He put an ad in gay publication The Advocate, inviting other gay Christians to join him setting up the MCC. He used his real name and address; Smith told him he was “crazy.” Others have called Perry brave over the years. “No, actually I was stupid. I didn’t realize you weren’t supposed to use your real name. The old homophile groups didn’t. But I didn’t care, because I wasn’t going to lie.”

The first meeting of MCC took place in the living room of Perry’s home in Huntington Park, with “nine friends and three strangers. Everyone was frightened every time anybody new came in the door.”

The group carried on meeting there, and then a women’s club. “When a venue found out who we were we would be thrown out—until we had a breakthrough at the Encore Theatre in Hollywood.” Articles in the Los Angeles Times and New York Times ensured more publicity, and new members. The MCC was finally able to purchase its own first building in 1971.

“In 1973 it was arson-ed and burned to the ground,” said Perry. “In our history about 20 churches have been arson-ed or defiled in some ways. We just kept going. I said, ‘I don’t care what they do. We’re never going to be chased out of a city.’”

Some members of the church, including an assistant pastor and his partner, were burned to death at the UpStairs Lounge fire in New Orleans in 1973, where 32 people died. (The New Orleans MCC chapter would often go to the bar after a service.)

In 1969, Perry sued California to recognize the validity of a marriage between two women he had performed, “but the judge laughed us out of court.” Perry himself successfully sued California in 2004 over refusing him and husband Phillip and their friends, lesbian couple Robin Tyler and Diane Olson, marriage licenses (Perry and De Blieck had originally married in Canada).

Then came the long path towards legalization—same-sex marriage was briefly legal in California, during which time Perry used his Book of Common Prayer to marry couples, then the passage of the discriminatory Proposition 8, followed by court challenges, ending with the legalization of same-sex marriage nationally in 2015.

Perry helped fight the anti-gay campaigning of Anita Bryant in the late 1970s, and the Briggs Initiative, aimed at preventing LGBTQ people from being able to teach in California. In 1979, Perry helped plan the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights.

At the 1993 March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation—attended by an estimated 800,000 to 1 million people—Perry married about 2,600 same-sex couples in front of the IRS headquarters. He has been invited to the White House on five occasions by Presidents Carter, Clinton, and Obama.

“To have lived this long and seen not only our history, but the history of the LGBTQ movement, has been incredible,” Perry said. “If you had told me we would have won marriage I would have called you a liar. That would be the last thing I would have thought.”

The Supreme Court’s decision that existing sex discrimination law applied to LGBTQ people was particularly heartening, as one of the young men photographed marrying in a 1971 MCC ceremony was fired after the magazine was published.

“The battles are not over in America, but I thank God for that one little Gay Pride parade we had in 1970. We called it ‘gay’ back then, everybody did.” Perry is proud that his work has led to him being a grand marshal in Pride parades the world over. “When a young GLBTQ person shows up to their first Pride and sees people like them, I hope they feel hope.”

Perry feels “discouraged” by the continued influence of the religious right, whose bigotry has been piloted by Mike Pence within the current administration, and the continued use of “religious freedom” as an anti-LGBTQ battering ram.

“I get so discouraged some days I don’t know what to do, because all people hear sometimes in my community and all they see is how bad religion can be,” said Perry. He can trade Bible passages with any bigot to make his pro-LGBTQ points. “I was raised in a fundamentalist background. They taught me scripture only too well. I always say to our clergy, ‘Throw it back in their faces.’”

Perry is more saddened when LGBTQ people “shut down” when they hear the word “Reverend” in front of his name. But he keeps it because he wants LGBTQ people not to “throw the baby out with the bathwater. Don’t give up because some fundamentalists from some religious group has told you that you can’t make a difference in the world. You’ve got to continue to struggle and fight. I tell young people, ‘I’m getting older. I’m going to die before long, it’s just the nature of things. Whatever you do, don’t give up the fight.’”

“I have had a wonderful, happy life.”

Perry and De Blieck celebrated their 35th anniversary on June 1. He laughed, recalling meeting his partner for the first time at an MCC service, which Perry himself does not remember.

Two and a half years later they met again in Perry’s favorite leather bar in Silver Lake. He was still grieving the death of a previous boyfriend—going home with guys and sometimes crying—when he looked up and saw De Blieck looking at him.

Perry gave his number to De Blieck, with the request he call him in two weeks, which he did. “We fell in love. We have traveled the world, and now 35 years later I am still madly in love with my partner. When you meet Mr. Right, you know without a shadow of a doubt you want to spend the rest of your life with them.”

Rev. Troy Perry, sitting, with husband Phillip Ray De Blieck.

De Blieck is 24 years younger than Perry. When his mother first met De Blieck, she said to Perry, “He’s the best-looking man I’ve ever seen. He has lovely manners. But Troy, he’s too young for you.” Perry gently reminded his mother that she too was 24 years younger than her first husband, his father, when they had met.

As he approaches 80, Perry says he doesn’t think about his own mortality much. “I know I’m going to die. I’m a clergyman who preaches about death. I performed my first funeral at 18 in the Pentecostal church for a little girl who had died. I know death and dying.”

The worst thing about aging have been ailments, such as suffering from diabetes, “but I keep it under control.”

“I have had a wonderful, happy life,” said Perry. “There is this wonderful old disco song, “Souvenirs,” by Voyage. I always think of memories as souvenirs of the incredible places and people I have seen and met around the world. Dying does not bother me. Philip knows that. He never wanted to talk about death, but in the last two years we’ve been able to cross that barrier. I’ve prepared my funeral service. That’s all ready.”

Perry’s activism and legacy is considerable, and he is proud of it. “I would like people—inside and outside the community—to remember me like, ‘He was faithful as a gay activist, faithful to his community. He always fought so hard.’ For me, that’s what I want people to remember.”

“I’ve lived this incredible life, thank God. My ministry, that’s what saved me,” Perry said. He paused for a moment, then added quietly, “I am who I am.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News