'As the tundra burns, we cannot afford climate silence': a letter from the Arctic

When you stand facing an exposed edge of permafrost, you can feel it from a distance.

It emanates a cold that tugs on every one of your senses. Permanently bound by ice year after year, the frozen soil is packed with carcasses of woolly mammoths and ancient ferns. They’re unable to decompose at such low temperatures, so they stay preserved in perpetuity – until warmer air thaws their remains and releases the cold that they’ve kept cradled for centuries.

default

I first experienced that distinct cold in the summer of 2016. I was traveling across Arctic Europe with a team of researchers to study climate change impacts. We were a few hours past the Finnish border in Russia when we stopped to first set foot on the tundra. The ground was soft but solid beneath our feet, covered with mosses and wildflowers that stretched into the distance until abruptly interrupted by a slick, towering wall of thawing permafrost.

As we stood facing the muddy patch of uncovered earth, the sensation of escaping cold felt terrifying.

The northern hemisphere is covered by 9m sq miles of permafrost. This solid ground, and all the organic material it contains, is one of the largest greenhouse gas stores on the planet. Frozen, it poses little threat to the 4 million people that call the Arctic home, or to the 7.8 billion of us that call Earth home. But defrosted by rising temperatures, thawing permafrost poses a planetary risk.

When the organic material begins to decompose, permafrost thaw can destabilize major infrastructure, discharge mercury levels dangerous to human health and release billions of metric tons of carbon. We witnessed small-scale damage in Russia that summer through slumped landscapes and uneven roads. At the time, the larger, more dramatic changes were predicted to unfold over the course of this century.

Four years later, those changes are happening much sooner than scientists predicted. The carbon-laden cold of the Arctic’s permafrost is leaking into Earth’s atmosphere, and we are not ready for the consequences.

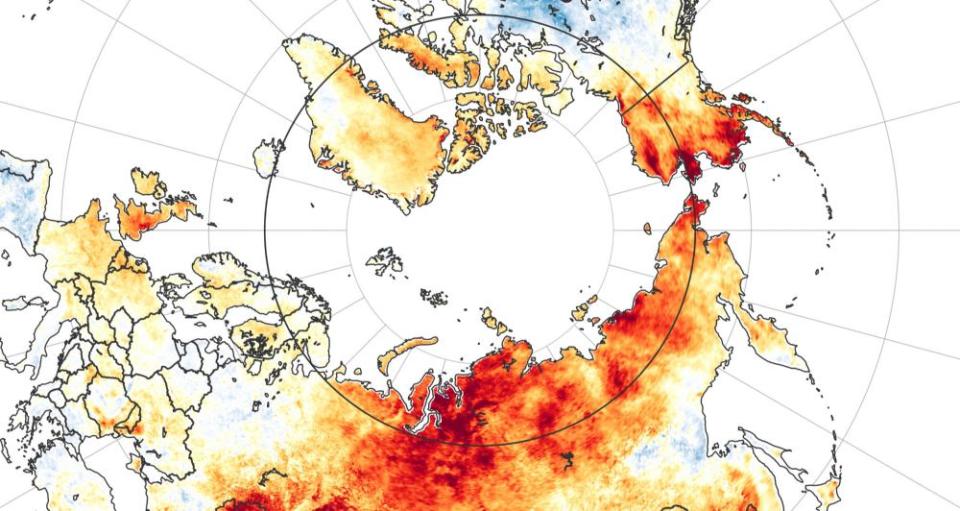

In June, the Russian Arctic reached 100.4F, the highest temperature in the Arctic since record-keeping began in 1885. The heat shocked scientists, but was not a unique or unusual event in a climate-changed world. The Arctic is warming at nearly three times the rate of the global average, and June’s single-day high was part of a month-long heatwave. This relentless heat has melted sea ice and made traditional subsistence dangerous for skilled Indigenous hunters. It’s fueled costly wildfires, some of which are so strong they now last from one summer to the next. And it’s sped up permafrost thaw, buckling roads and displacing entire communities.

Watching the heat of 2020 devastate the Arctic, I think back to the fear we experienced while watching that permafrost thaw in 2016, but I also remember feeling hopeful.

Just weeks before our expedition began, 174 countries had signed the Paris agreement on the first day it opened for signatures. Barack Obama and China’s President Xi Jinping released a joint statement of climate commitments for the world’s two largest greenhouse gas emitters. It seemed like every world leader had finally dedicated themselves to climate action. Throughout our trip across the Arctic, my colleagues and I discussed the difficulties of limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees, but, with the momentum of Paris, we agreed that it was still possible to contain a climate catastrophe.

It is much harder to find hope today than it was four years ago – but it’s not impossible.

The Arctic’s skies are blackened with wildfire smoke and we are not even halfway through summer. The Trump administration has reversed 100 environmental rules and stands on the precipice of pulling the US out of the Paris agreement in November 2020.

Things may seem hopeless, but we are not helpless.

Every individual has a skill, a voice, a career to wield as a tool to address climate change. Ultimately, climate action is not powered by the Paris agreement – it’s powered by people. From presidents to protesters, we each have a part to play in limiting the devastation of the climate crisis.

Climate change cannot be stopped. The Arctic’s ice will melt and large swaths of frozen ground will thaw. Climate change is already causing devastating loss of life, destroying irreplaceable cultural heritage and inundating the places we hold dear. With every degree we allow our world to warm, the more we lose. But by demanding climate action from our governments, and demanding climate action from ourselves, we can work today to avert the worst damage and adapt to the impacts we can no longer avoid.

As the Arctic burns, we cannot afford climate silence from anyone. The cost of inaction is too high.

Dr Victoria Herrmann is the president and managing director of the Arctic Institute

Yahoo News

Yahoo News