Two images that show we need to be sensitive about our photos

Khalid Masood was lawfully shot dead by police after he killed five people at Westminster in March 2017, a coroner’s inquest in London concluded on Friday. Over several days of covering the hearing, Guardian editors had access to a limited range of images of Masood. For one report they used a photo of him taken in the Great Mosque of Mecca, Islam’s holiest site.

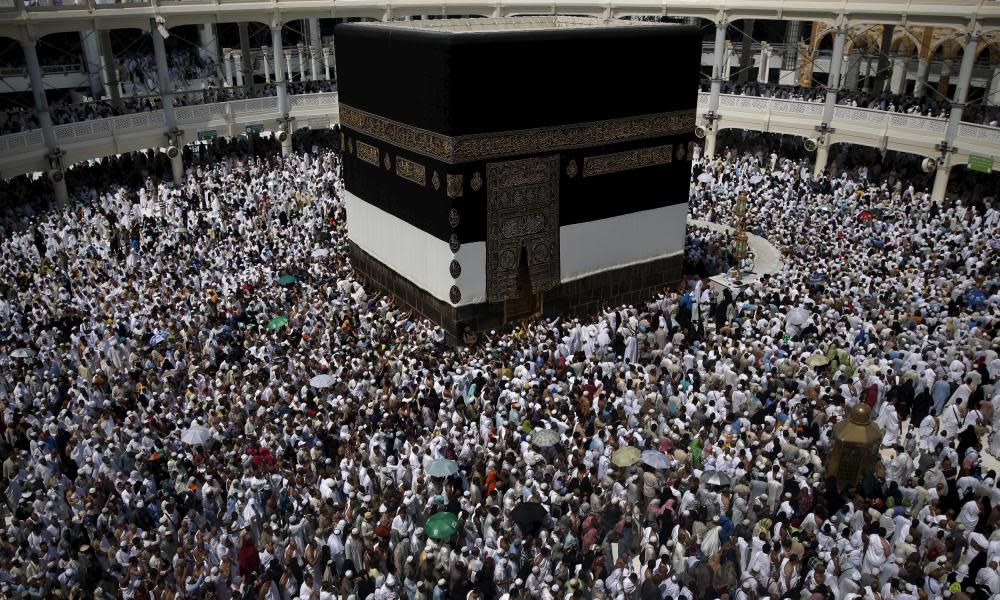

Some Muslim readers expressed to me concern that the image linked a particularly important aspect of their religion to the awful crimes of this individual. One of the five pillars of Islam is for Muslims, if physically and financially capable, to make the Hajj, a pilgrimage to the site, at least once in their lifetime.

From an editorial standards perspective, there was nothing wrong with the image. Legitimately obtained, it depicted a smiling Masood dressed in the traditional white, and behind him the Kaaba, the great cube, around which pilgrims walk seven times.

Conscious that the Muslim community can suffer discrimination when terrorist acts are committed in the name of a political ideology that feigns religiosity, as a gesture of goodwill the editors replaced the photo for another image, a police mugshot. Muslims who had raised the issue were appreciative.

It is essential that journalists cover the crimes that constitute terrorism, and the legal processes which follow. Coverage can justifiably include images of perpetrators but should take care not to glorify them. Had the photo related directly to evidence given in the inquest it might have been necessary to retain it.

A different case of image sensitivity arose from an online gallery of 29 photographs taken at Tarragona, Spain, where teams compete to form the highest and most complex tower of interlinked humans. A feature of Catalan culture, the “castellers” demonstrate great feats of strength, balance and daring; but most of all, it seems to me, of trust and unity.

The towers collapse at times, and one image online shows the aftermath. The camera looks down from above at a man lying on his back surrounded by team-mates. The beautifully composed image evokes El Greco. A plea arrived by email in my office. The writer, who seemed close to the event, said the man had been unconscious. The message was ambiguous about whether he had later died. It respectfully requested that the image be deleted in recognition of grief, privacy and “the integrity of the injured person”.

Depictions of distressed, seriously injured or dead persons need to be handled with care. The editors checked with the suppliers of the images and learned that the man had regained consciousness and was recovering from a shoulder injury.

I agree with the editors’ decision to keep the image online. It is one part of a public cultural event in which danger and injury are elements of a truthful account. The reader took the explanation in good heart.

Reasonable people can differ on these kinds of calls, but in my time in this role I have been consistently impressed by the willingness of Guardian editors to consider, reconsider and explain their decisions.

• Paul Chadwick is the Guardian’s readers’ editor

Yahoo News

Yahoo News