The UK was a global leader in preparing for pandemics. What went wrong with coronavirus?

It’s difficult to imagine that Britain was, until very recently, regarded as a leader in preparing for pandemics. Countries such as Singapore once looked to the UK for lessons in how to prepare for and respond to outbreaks. Now, it’s the other way around. With its number of coronavirus cases exceeding 170,000, and deaths set to climb above 40,000, the UK appears to be playing catch-up with the rest of the world.

Britain’s failure to shatter the coronavirus curve couldn’t be further out of step with its past reputation as a leader in this area. The UK’s global health strategy, launched under New Labour in 2008, was a game-changer in the field of global health. The strategy identified how, in an interconnected world, an infectious outbreak in another country was a direct threat to the UK. By building health capacity elsewhere in the world, the government recognised that it could protect its own borders from infectious outbreaks – reflecting the Blairite logic that interventions abroad would bolster security at home.

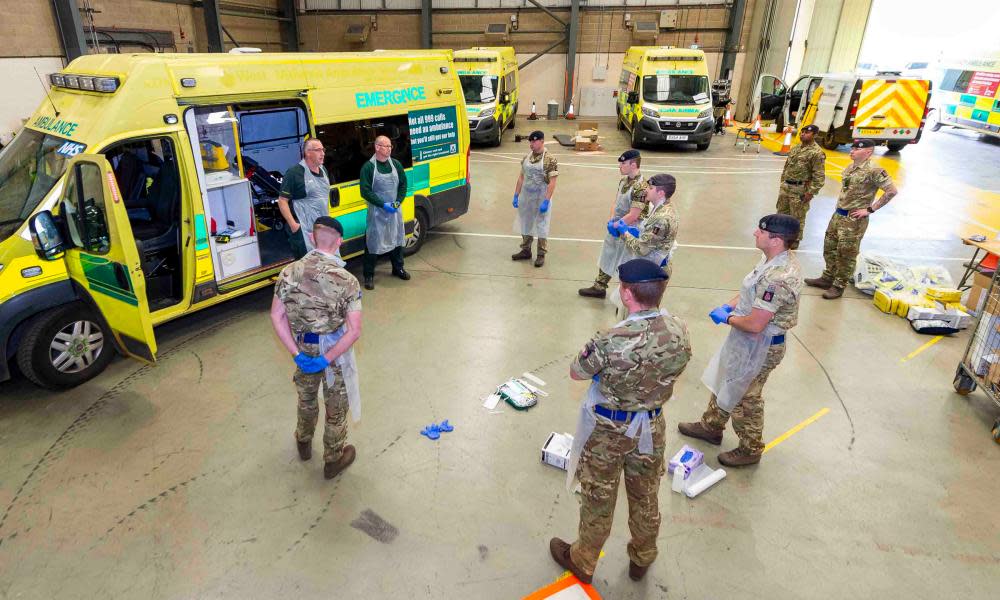

Over the past two decades, the UK has been a trailblazer in funding global health. It’s one of the only countries to have 0.7% of GDP earmarked for overseas development assistance. Public Health England has a global team advising countries across the globe in building capacity to respond to disease, while the UK’s public health rapid support team is frequently deployed around the world to support countries’ response efforts to emerging pathogens. During the Ebola crisis in 2014, for example, the government deployed PHE epidemiologists to work with Sierra Leone’s health ministry, while the Ministry of Defence sent troops to build treatment centres and NHS staff volunteered as healthcare workers. Meanwhile DfID supported clinical trials of vaccines, in collaboration with UK universities.

Of course, the UK’s interests in this field were never just about health. Its 2008 strategy was criticised at the time for self-interest – pursuing health policies abroad primarily as a means of protecting the UK from infection, and as a trade opportunity to commodify NHS expertise on the international market. In the febrile political climate that followed 9/11, the threat of an attack – whether in the form of a virus or a terrorist group – loomed large in governments’ imaginations. The UK government saw policies to combat infectious diseases as an extension of this security mindset – in turn shaping how politicians came to view pandemics.

This fear of existential risks forged the UK’s global health strategy, but it also helps explain why we found ourselves on the back foot when coronavirus hit. By the time Covid-19 arrived, the memory of such dangers taking place at home had faded; outbreaks seemed like things that happened elsewhere in the world. The last major outbreaks to affect the UK were BSE in the early 1990s and the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak in 2001. While these both posed significantly less of a risk to human mortality than Covid-19, they contributed to widespread disruptions and substantial economic losses for farmers. By the time the last foot-and-mouth case had been recorded, in Cumbria, more than six million cattle, pigs and sheep had been slaughtered. Yet in the years that followed these crises, successive governments became complacent – believing they could get away without funding preparedness, as outbreaks were unlikely to happen within their election cycle, if at all.

This complacency was amplified by austerity policies. The NHS has endured the most prolonged funding squeeze in its history, which has meant that surge capacity in PPE, ventilators and ICU beds was not purchased, even when Operation Cygnus identified these areas as shortcomings in 2016. Meanwhile the UK’s cuts to investment in public health areas such as smoking, alcohol and obesity have contributed to a rise in entirely preventable chronic conditions, which are now proving significant risk factors for coronavirus.

One of the few existential dilemmas the UK has faced over the last decade is Brexit. Somewhat paradoxically, in prioritising Brexit, government ministers dealt another blow to the UK’s preparedness for a threat whose consequences would be deadly. Training for key workers to manage a pandemic was stalled to make space for contingency plans around no-deal Brexit, while the UK missed opportunities for EU-level purchasing of PPE, and parliamentary enquiries into preparedness for infectious disease were delayed and eventually halted due to the 2019 election.

Early in the pandemic, the UK made the significant – and potentially fatal – decision to ignore the advice of the WHO, an institution for which the UK is still a top government funder, which recommended a strategy of testing, isolating and contact tracing. This early move now seems like a grave mistake. Jenny Harries, England’s deputy chief medical officer, stated that the UK didn’t need to follow WHO advice – “The clue with the WHO is in its title – it’s a World Health Organization, and it is addressing all countries across the world,” she said at the time.

But the assumption that WHO guidelines didn’t apply to us exposed a remarkable hubris in the UK government’s approach to coronavirus. We were no better prepared than the rest of the world. Indeed, we were worse prepared than countries that once looked to us for lessons. On matters of pandemic preparedness, why would any government seek the UK’s advice again?

• Clare Wenham is assistant professor of global health policy at the London School of Economics

Yahoo News

Yahoo News