UK immigration latest: EU net migration falls over past year as Brexit uncertainty continues

EU net migration is falling as more European citizens leave the UK and fewer arrive in the wake of the vote for Brexit, new statistics show.

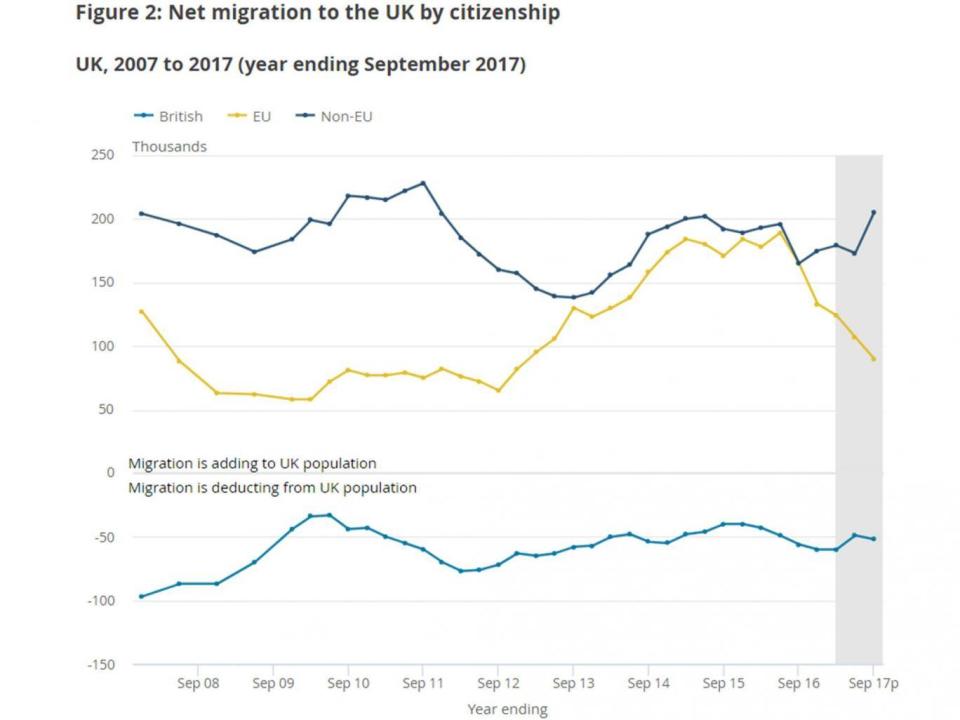

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) said net migration in the year to September was 244,000 people – a similar level to early 2014 and down on record levels in the next two years.

The number of European citizens arriving has plummeted since the EU referendum, while the number of people from outside the bloc has increased.

“EU net migration has fallen as fewer EU citizens are arriving, especially those coming to look for work in the UK, and the number leaving has risen - it has now returned to the level seen in 2012,” said Nicola White, head of international migration statistics at the ONS.

“The figures also show that non-EU net migration is now larger than EU net migration, mainly due to the large decrease in EU net migration over the last year. However, migration of both non-EU and EU citizens are still adding to the UK population.

“Brexit could well be a factor in people’s decision to move to or from the UK, but people’s decision to migrate is complicated and can be influenced by lots of different reasons.”

The number of EU citizens coming to the UK plummeted by 47,000 in the year and the number leaving – 130,000 – is the highest recorded level since the 2008 financial crisis.

Almost a quarter of a million people arrived in the UK to work in 2017, with the number of EU citizens falling by 58,000.

Most of the Europeans arriving had a definite job lined up, while a smaller proportion were looking for work.

The biggest nationality starting work in the year to September, according to National Insurance number registration data, was Romanian, followed by Polish, Italian, Bulgarian, Spanish and Indian - who accounted for more than half of all skilled work visas granted.

The ONS said that the overall employment rate for EU nationals was 81.2 per cent, followed by Brits at 75.6 per cent and non-EU nationals on 63.2 per cent.

George Koureas, a partner at immigration law firm Fragomen, said: “The UK has become a significantly less attractive place for European citizens to work since Brexit, so it’s no surprise that more EU workers are leaving the country.

“Although the Government may see this as good news, it presents a significant threat to UK businesses, already struggling to hire the skilled workers they need to thrive.”

He said there could be a further impact from the Government’s plan to double the Immigration Health Surcharge, which is paid by migrants to use the NHS, and caps on visas for skilled workers.

“Businesses have little choice but to recruit workers from further afield and absorb the high cost of doing so,” Mr Koureas added.

“The Government must take assertive steps to reassure UK plc by removing shortage occupations, such as NHS workers and engineers, as well as graduates, from the Tier Two visa cap in order to allow businesses to recruit the workers they need.”

Professor Jonathan Portes, senior fellow at The UK in a Changing Europe unit at King’s College London said migration shifts could be driving a slowdown in Britain’s relative economic growth.

“Falls in EU migration are already adversely affecting some sectors, for example the NHS, where they have aggravated existing staff shortages,” he added.

“The reduced availability of EU workers also appears to be interacting with the UK’s absurd quota system for highly skilled migrants from outside the EU, which in turn means that we are denying visas for desperately needed specialist doctors from outside the EU.

“This illustrates, yet again, the inevitable unintended consequences of the Government’s determination to centrally plan the UK labour market.”

In 2017, the UK took in almost 15,000 refugees - 40 per cent of them children - through resettlement programmes and granting asylum or other forms of protection.

A rising number of people were resettled from other countries, such as those surrounding Syria, but the number of family reunion visas, granted asylum and protection applications were down.

Of the 20,000 Syrian refugees the Government pledged to take in in 2015, more than 10,500 have now arrived in the UK under a dedicated resettlement programme.

Home Secretary Amber Rudd said the initiative would hit its target early and announced she is holding talks on what could follow the scheme as the Syrian civil war continues to intensify.

“Twenty thousand is definitely achievable by 2020 and I hope that we may get there earlier than that in fact, and at the moment I am consulting with stakeholders and really engaging with other departments to decide what we should have to replace that when we go forward after 2020,” she said.

“It is the largest number of any European country of resettlement from the region, it is the largest the UK has done from the region and people have been very kind about saying how effective it is and how good the care is when people get to the local authority.”

Caroline Nokes, the immigration minister, restated the Government’s commitment to bringing net migration down to the tens of thousands.

“This means an immigration system that attracts and retains people who come to work and bring significant benefits to the UK but does not offer an open door to those who don’t,” she added.

“Net migration remains 29,000 lower than it was a year ago and once we leave the EU we will be able to put in place an immigration system which works in the best interest of the whole of the UK.

“At the same time, we have been clear that we want EU citizens already living here to have certainty about their future and the citizens’ rights agreement reached in December provided that.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News