UK needs EU scientists’ help ‘to be a successful country’ after Brexit, government’s new science chief says

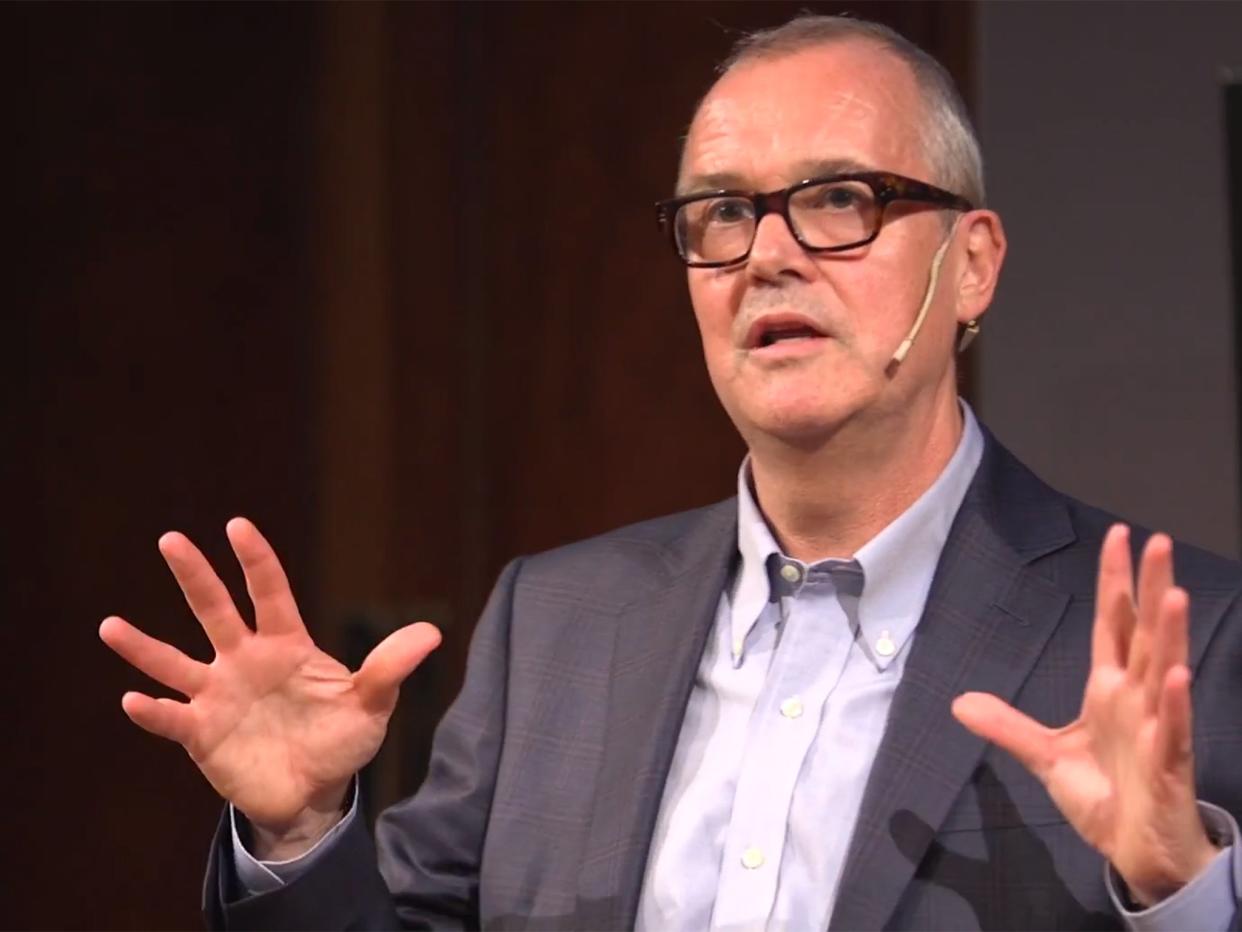

The UK must maintain existing relationships with its European neighbours after Brexit or face a serious decline in its scientific activities, the government's chief scientific adviser has warned.

“I think there’s no question that if you want to be a successful country scientifically you have to be international, you cannot be parochial,” said Dr Patrick Vallance who took up his position in April.

British science currently relies on the European Union for a sizeable chunk of funding and over half the researchers working in the UK were born overseas.

Scientists on both sides of the Channel broadly agree it is in everyone’s interest for the UK to maintain a similar level of cooperation with Europe following Brexit.

But Dr Vallance warned that such future cooperation is not a “foregone conclusion”.

In the meantime, he said it would also be important to look beyond Europe and forge more links with the US and Commonwealth nations to “renew our commitment to international collaboration”.

He said: “Our nearest neighbours are outstanding scientists – they have got great universities, great laboratories, great science-led businesses – and we have absolutely got to keep that going.

“If we are going to be successful as a country in our economy and our society we have to be successful in our science.”

He said the deal being pushed for by the government is striving for a system where science being conducted with our European neighbours is not interrupted.

In a speech given in May at the Jodrell Bank Observatory, Theresa May said she valued this collaboration and wanted to retain full association with the EU’s proposed €100bn (£88.9m) research and innovation scheme – the successor to its Horizon 2020 programme.

However, some have questioned the feasibility of retaining all of the current benefits enjoyed by the UK science community following Brexit.

“We would share those aspirations, but we think there is a gap in how the government intends to deliver on them,” said Sue Ferns, deputy general secretary of scientists’ trade union Prospect.

“Horizon 2020 was an important source of funding for many UK scientists – clearly the government wants to have access to the successor but the widespread expectation is that we will be paying more and getting less out.”

Concerns also remain about the free movement of scientists and their families, and the UK has already parted ways with European collaborations such as the Euratom nuclear agency and the Galileo satellite programme.

In an interview with The Independent, particle physicist and TV personality Professor Brian Cox said there is “no upside” to Brexit for UK science – a view that has been echoed by many important figures including the Royal Society president Venkatraman Ramakrishnan.

Nevertheless, Dr Vallance said the government is pushing for the best deal possible for scientists.

“Although there’s good will on both sides and the scientists want it, it is not a foregone conclusion ever until you’ve done it so we need to keep focused on that, and the prime minister is quite clear on what she wants from this,” he said.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News