UK at risk from ships covertly sailing into Europe after 'suspicious stops' near terror strongholds, say security analysts

Ships from conflict zones and terrorist strongholds are covertly sailing into European waters on suspected smuggling missions while attempting to evade detection, security analysts have warned.

Research by the Windward maritime data company found that in the first two months of 2017, 50 vessels with invalid registration numbers entered the UK, and 245 more with “suspicious” gaps in tracking data.

Another 40 ships sailed into Europe from near Isis-controlled territory in Libya after unexplained black-outs on their automatic identification systems (AIS) during January and February.

Ami Daniel, the firm’s CEO and cofounder, warned that the cases found so far are just a small fraction of covert voyages in Europe.

“There is a void,” he told The Independent. “No one is looking at what’s coming at sea – everyone is looking at planes, everyone is looking at land borders but no one is looking at shipping.

“It’s frightening but it’s the reality.”

The International Maritime Organization (IMO) requires all ships to be assigned a unique reference number that can be combined with AIS data to avoid collisions and monitor movements, course and speed.

But Windward found numerous cases where fake IMO numbers were being assigned to large cargo vessels, as well as blips in tracking that appeared to lengthy to be accidental.

Mr Daniel said AIS equipment, which communicates with satellites, is mandatory for all large international ships and passenger vessels.

“These are safety transmissions so definition you would not turn that off,” he added.

“People who turn off transitions are doing a trade-off in their minds.”

Analysts believe such a trade would most likely be made for illicit reasons to evade authorities, possibly while carrying illegal cargo such as weapons, drugs or people.

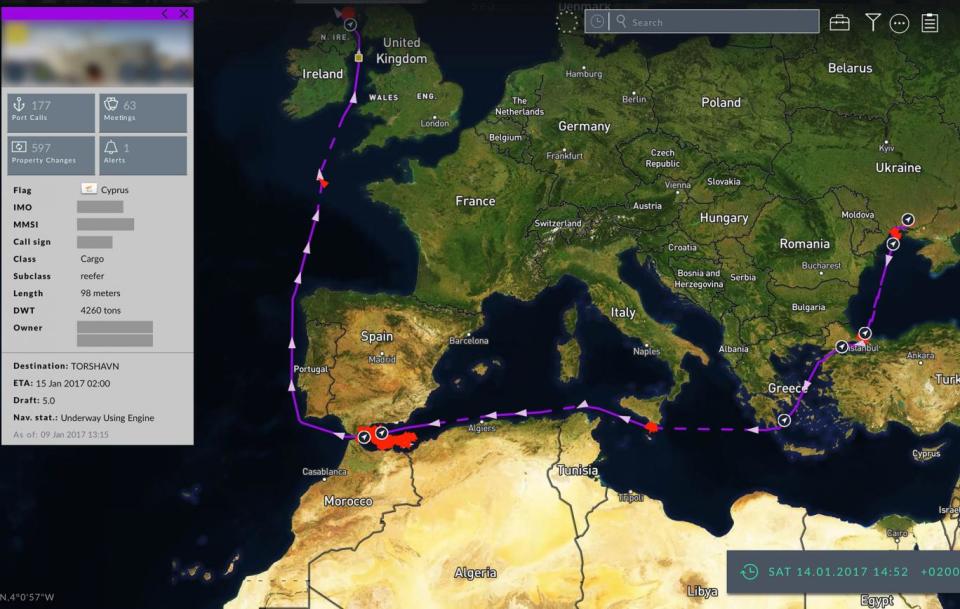

One of the vessels tracked was a Cyprus-flagged cargo ship owned by a Russian company, which broke from its normal pattern of voyages between Northern Europe and West Africa last month.

It diverted via the Mediterranean Sea to make its first port visit in Ukraine in December, before sailing back towards Gibraltar and engaging in “12 days of suspicious drifting” where the AIS repeatedly stopped transmitting.

The ship went dark near the port of Oran in Algeria, where gangs are active trafficking migrants, narcotics and illegal arms, and al-Qaeda is waging an Islamist insurgency.

On 9 January, it set sail for the UK and arrived in Scotland five days later, performing a “suspicious stop” off the coast of Islay for 11 hours, when analysts said illicit cargo may have been loaded on to smaller boats.

“The UK’s coastline is vulnerable,” a report by Windward found. “The maritime domain is vast and laws are difficult to enforce.

“Ships with criminal or terror-related intentions can easily conceal their cargo – arms, drugs or people.”

Although ships arriving in EU ports have to declare their last calling point, researchers say the measure does not take account of behaviour at sea including diversions and offshore transfers.

As well as fake registration numbers and disappearing location transmissions, more than half of all vessels entering the UK were using “flags of convenience” – linked to tax avoidance, regulation dodging and crime – as well as hundreds had ship-to-ship meetings just outside territorial waters.

There is particular concern over ships leaving conflict zones including Libya, Syria, Yemen and Somalia, which have been tracked carrying out “suspicious movements” off the coast of Greece and other European nations.

Many lose transmission while anchoring around a mile offshore – far from port but close enough to land for smaller vessels to transfer goods.

“You might have ship come out of Libya, conduct a ship-to-ship transfer near Malta, change registration numbers and someone has done business with Isis,” Mr Daniel said.

Smuggling gangs based in the war-torn country packed disused cargo ships and fishing vessels with hundreds of refugees at the start of the Mediterranean crisis, sailing them into open water before calling for aid and abandoning what became known as “ghost ships”.

Unseaworthy dinghies are now dominantly used but there have been reports of groups using commercial vessels to transport migrants from port to port before launching them towards Europe.

Mr Daniel, a former officer in the Israeli navy, said the world of shipping presented an easier method of expansion for terrorist groups and criminal organisations than more tightly regulated airports and land borders.

“They can transport people, weapons, drugs, they can finance wars,” he added. “It’s still the Wild West in these seas.”

European crime agency Europol said it was monitoring people smuggling as part of the refugee crisis but that the primary responsibility for maritime security lay with member states.

A Home Office spokesperson said: “Border Force monitors vessels sailing off our coastline for suspicious behaviour, including the disruption of AIS.

“The National Maritime Information Centre brings together officers from Border Force, the National Crime Agency, police, Royal Navy, coastguard and others to share intelligence, detect and respond to a range of threats.

“This approach is working. In 2015, a vessel carrying more than three tonnes of cocaine was detected despite turning off its AIS system.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News