UN-EU conference falls $5bn short of Syrian aid target for 2018

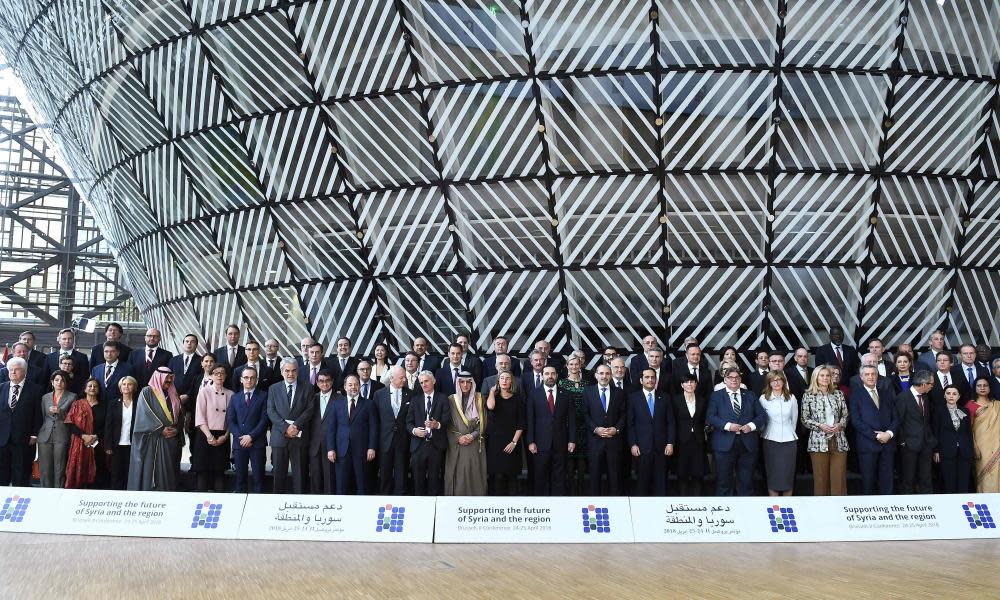

Syrian refugees are facing a large shortfall in aid after a two-day joint UN-EU pledging conference in Brussels fell billions of dollars short of the UN target for 2018.

The $4bn (£2.9bn) raised was less than half of the $9bn the UN says is needed this year to help those in need inside Syria and living as refugees in neighbouring countries. The shortfall prompted UN agencies to say some programmes may need to be cut.

Mark Lowcock, the UN under-secretary for humanitarian affairs, said the shortfall would require the UN to prioritise, stressing help should go to those most in need and most vulnerable, but that that would require more UN staff inside the country.

“We would have liked our appeal to be fully funded. We are talking about a vast sum of money and there is a lot of pressure on the financiers,” he said.

The $4bn is lower than the sums raised at a similar conference last year, partly due to a delay in a $1bn US pledge and continued discussions between the EU and Turkey over the details of a package agreed two years ago, designed to help Turkey handle 3.5 million refugees.

UN officials nevertheless described the aid package for 2018 as a good start and said the figure could rise on the basis of progress last year.

The bulk of the money raised at the conference itself came from Germany, the EU, and the UK. British hopes of a large pledge from Gulf states did not materialise. Britain itself pledged a further £250m, including help to train doctors and nurses in trauma care.

The UN had said it was aiming for a total of $3.6bn for a humanitarian response plan for those in need inside Syria, of which $800m (23%) had been pledged before the conference. Separately the UN was seeking $5.6bn for refugees on the Syrian borders, of which $1.2bn has already been committed in earlier conferences.

The funds are not designed for the reconstruction of Syria, something Federica Mogherini, the EU foreign affairs chief, said could only start after a full peace settlement was in place.

The relatively low level of funding came despite strong appeals from ministers in three of the countries bordering Syria – Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan – that extra funds were badly needed to prevent tensions between its nationals and Syrians spiralling out of control.

The Lebanese prime minister, Saad Hariri, who is facing elections in two weeks, said: “The bitter truth is conditions have deteriorated for refugees since last year,” adding “Lebanon remains a big refugee camp”. He said: “Tensions between Syrians and the Lebanese community is on the increase due to competition for jobs.”

The Turkish deputy prime minister, Recep Akdağ, blamed the EU for “a disappointing failure to share the refugee burden”. He said his country had played a major role in preventing one of the major crises of the EU by agreeing to control the irregular flow of people across the Aegean.

He said the EU had not fulfilled its pledges on visa liberalisation for Turks to enter the EU, a central part of the initial deal that has led to a cut in the number of people crossing the Aegean from 7,000 daily to fewer than 50.

The Jordanian foreign minister, Ayman Safadi, said that unless the international community stopped simply managing the crisis it would leave a well of bitterness among the 1.3 million refugees inside Jordan, and “a new army of Islamic State” would come into being in 10 to 15 years. He stressed a political and not an aid settlement was required, and that that involved accepting new realities.

The UN special envoy for Syria, Staffan de Mistura, fresh from talks in Moscow at the weekend, also briefed the conference saying the recent western attacks on Syrian chemical weapons sites had been a wake-up call prompting high-level diplomatic discussions.

He suggested the Russian-led Astana peace process, sometimes regarded as a Russian and Iranian rival to the UN process in Geneva, was in danger of showing its limits. He pointed out there had been a re-escalation of violence in 2018 and a failure after a year to deliver on the issue of detainees, prisoners and missing people.

He also said there had been no follow-up to an agreement at a large peace conference, hosted in the Black Sea resort of Sochi by Vladimir Putin, to set up a constitutional commission on the future of Syria. “Sochi risks being considered to have produced a stillborn unless there is more proactivity about the constitutional commission,” he said.

Even though the idea of a large constitutional commission was proposed by Russia, the idea was rejected by Bashar al-Assad as a foreign-inspired move.

Russia has made little public reference to the plan since then, but foreign ministers from Turkey, Russia and Iran will meet in Moscow this weekend.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News