How to understand blockchain using emojis: part one

Welcome to our easy-to-understand guide about blockchain technology using emojis.

It's not the easiest topic to understand. Blockchain, the technology that underpins the cryptocurrency bitcoin, is also known as distributed ledger technology.

It's like a distributed database, where millions of computers around the world have access to the database and are constantly updating it by recording bitcoin transactions.

But why did it start and what purpose does it serve?

Let's go back to the beginning.

What is blockchain: the background

The story of blockchain began in 2008, when a mysterious person named Satoshi Nakamoto released a paper called ‘Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system’.

Who is this mysterious Satoshi Nakamoto?

Like Spartacus, Zorro and Banksy before, many have claimed to be the great Satoshi, yet no one knows who they really are. They have remained anonymous throughout the rise of bitcoin and the subsequent rise of blockchain technology.

There have been many attempts to find Satoshi through analysing their posts and correspondences, but no conclusive evidence has been found. What we do know about Satoshi is that, in 2008, they were familiar with recent research in cryptography, and they didn’t like banks.

In early January 2009, the first block of the bitcoin blockchain was created (mined). It included a headline from The Times: "03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks".

This headline provided a timestamp for the first block. This is similar to when in hostage situations in videos, the hostages often hold up that day's newspaper to show they were still alive on a certain date.

So this message was in the first block of the bitcoin blockchain…but what is a block and why is there a chain of them?

To answer this, we must first discuss Satoshi’s fundamental reason for creating bitcoin.

Essentially, it is to remove “trusted third parties” from financial transactions. And, by trusted third parties, in simple terms, they mean banks.

The current banking system

For clarity, let’s simplify the current “centralised” banking system to a basic system with just one bank which everyone uses. The role of this bank is simply to record all the transactions between payers and payees. A transaction might read something like ‘Alice pays Bob 10 coins’.

However, every transaction we make online doesn’t just go from the payer to the payee. It goes from the payer to the bank and then to the payee.

Financial systems

The bank enables and records every financial transaction we make (disregarding cash transactions) and it, therefore, has complete control over our finances.

The bank also takes a cut of many transactions, especially when money is sent across borders.

Controlling this list of transactions, called the ledger, gives the bank power over the finances of the users. If the bank decides to alter the ledger, who can stop them?

Based on this, Satoshi’s initial aim was to create a financial system without a bank.

A financial system without a bank

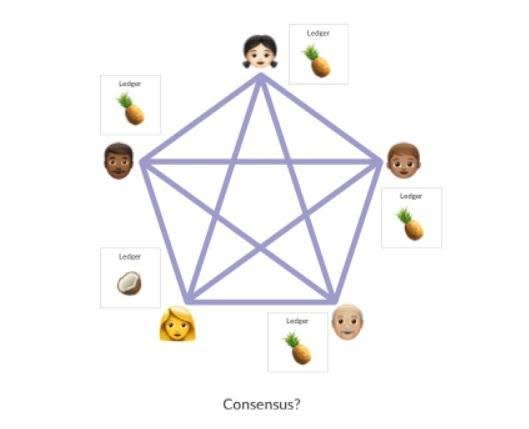

The first step towards removing the bank from this simplified financial system is to take the ledger of transactions from the bank and make it public. So let’s give the ledger to the users of the system… but to how many of the users?

Well logically, the ledger must be given to anyone who wants it, because how else do we remove a trusted third party from the system? If half of the users control the ledger but the other half do not, then the first half are in a position of power and must act in a trustworthy way.

In order to completely remove a trusted third party of any sort, the only solution is to allow every user of the financial system to maintain and update the ledger.

Ok …but that seems like a lot of copies of the ledger if everyone has one, but let’s go with it for now. Is this going to work?

Well, w immediately come across a problem. If everyone has a copy of the ledger, how do we ensure that all the ledgers are always saying the same thing, i.e. that they are all in consensus?

For example, suppose a transaction happens, say ‘Alice pays Bob 10 coins’, and it is broadcast across the network.

Some users, upon receiving this transaction, add it to their ledger. However, a few users don’t receive this transaction due to connectivity issues.

In this case, there needs to be some way for the network to agree upon the “most correct” version of the ledger across all of their versions of the shared ledger.

But agreeing on such a version of the ledger leads to a problem called the double spending problem, where a crook can exploit differences between the many copies of the ledger and spend some digital coins twice!

How the Double Spending Problem works

Let’s suppose I am the devious user in the decentralised network and I have 10 digital coins in my account. I am going to try and spend these digital coins twice to buy coconuts and pineapples (I’m making piña coladas).

Now, it is important that we don’t view these digital coins as physical objects (like in so many of the bitcoin article pictures) because it would be impossible to spend any physical object twice.

If I gave you a £1 coin, there is no clever way of spending it again without just taking it back off you. However, with digital money, it becomes possible just as we can duplicate a file on a computer so that two people can have a version of the same file on their own computers.

Suppose I have 10 digital coins in my account and the network is in consensus on this amount, i.e. everyone’s ledger agrees that I have 10 digital coins.

I begin by visiting my friend Alice to buy some coconuts. She is the best coconut vendor in town. I transfer her my 10 digital coins and she adds the transaction to her ledger.

She gives me the coconuts. But I know that Alice’s internet is slow, so I thank Alice, I make my goodbyes, and I quickly leave.

I immediately run down the street to my friend Bob’s house. Bob sells pineapples and I want to buy some. They cost the same as the coconuts, the full 10 digital coins.

Now since I have been so quick in getting to Bob’s house, my coconut transaction to Alice has not yet reached Bob across the decentralised network, and so, when he looks at his version of the shared ledger, it appears to him that I still have 10 digital coins in my account.

Therefore, Bob is happy to accept my transaction and we submit it to the network on Bob’s computer.

With my actual intentions hidden, I urge Bob to immediately forward the pineapple transaction to everyone in the network so that the money is safely his. Fortunately, he has fibre optic internet and his message gets out to 99 per cent of the network while my coconut transaction to Alice only gets out to a few people.

Since the majority believe Bob to be the rightful owner to my digital coins, they convince the rest of the network of this, and Alice is sadly left out of pocket.

Now, in this case, Alice could just come and find me and demand her money back or at least her coconuts.

But what if I am an anonymous online purchaser? Then Alice has simply been conned.

In this way, I have attacked the system and spent the same 10 digital coins on coconuts and pineapples, and I’m making cocktails!

This is called a double spending attack in academic literature.

How to prevent the double spending problem through the blockchain

When transactions are immediately added to different versions of the shared ledger, I can sneakily spend the same digital coins twice. So we need a way to prevent a double spending attack.

We will see that blockchain technology does just that.

Incentivisation

So that is the double spending problem in a coconut shell. But aside from the double spending problem, there is also another issue. Why would people bother to look after this distributed shared ledger in the first place?

It seems like a nice idea, but updating and maintaining it is hard work. It costs a lot of time and money, mainly expended on electricity.

For many people, their dislike of banks only goes so far. Users need to be incentivised to maintain the shared ledger correctly. Otherwise, they will just go back to using the old centralised banking system.

Blockchain with emojis: recap

To recap, we have hit some problems with our first attempt at a decentralised shared ledger.

1. Lots of copies of the shared ledger, one for each user.

2. How can we incentivise the users of the network to maintain the ledger?

3. Double spending problem.

It is at this point we need a bright idea, and Satoshi provided just that. In the bitcoin white-paper, they came up with a revolutionary idea to solve problems two and three at the same time.

This idea is called a blockchain.

Patrick Woodhead is co-founder of Pilcro

Yahoo News

Yahoo News