UNESCO Week of Sound: “We find ourselves in a crisis situation”

The UNESCO Week of Sound celebrates its 20th edition this year.

This public event taking place in France until 29 January also reaches out to many UNESCO member countries, and offers a unique opportunity to promote the good practice of sound.

A vast topic, especially when sound is becoming, now more than ever, an omnipresent element that shapes our relationship to the world around us. At home, at work, in the street, in a restaurant, during a concert… The environmental, societal, medical, and cultural implications are numerous and everyone is confronted every day with the various powers of sound. Often without even realising it.

The Week of Sound association, now recognized by UNESCO, aims to enhance the awareness of sound in our daily lives and addresses the societal issues and challenges relating to sound.

Euronews Culture spoke to Christian Hugonnet, graduate engineer from the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers, acoustics specialist and President of the association La Semaine du Son (Week of Sound), to find out how the absence of silence can lead to aggression, whether the way we listen to music can be detrimental to our health, and discuss the reasons behind this year’s theme: “Savoir écouter, savoir se parler” - “Knowing how to listen, knowing how to talk”.

Euronews Culture: What was the original idea behind founding the Week of Sound 20 years ago?

Christian Hugonnet: It was an awareness that seemed essential, especially considering my background in radio, television and also my work on music and acoustics. There was already a Week of Taste at the time, and I thought: We need a Week of Sound.

We operate in a retinal setting, that is to say that we observe the world and that often means forgetting to listen to what’s going on. I thought it was important for us to focus our behaviour on listening to see better. It’s not about listening instead of seeing, but listening to see the world around us better. Jacques Attali, who has been one of the Week of Sound’s godfathers, said: “The world isn’t observed, it’s listened to first.”

It takes place every third week of January…

Yes, to better start the year! It takes place over two weeks, not only in Paris but in all the French regions, with the idea of valorizing sound through five themes. Because that was the main difficulty at first: What are we talking about when we talk about sound?

So, I zoned in on five essential elements. The first is the sound environment, or soundscapes, if you will – the thing that englobes us and directly affects our behaviour. The second is the recording of sound – the majority of people go less and less to concert halls and everything right now takes place through mediums like speakers and earbuds, so it’s about mastering and monitoring this sector of activity.

The third theme is auditory health – we have ears and we need to protect them. The World Health Organization currently counts around 1.3 billion potentially hearing-impaired people around the world, which is huge, as it represents around one out of five people. The fourth theme is about the link between images and sound, with cinema and television, to better understand that sound is a trigger for images, and not the opposite way around. When we hear, we see better, but when we have an image, we don’t necessarily hear what goes on. That’s the case with cinema, but also with architects and urban landscapers.

The final theme is music, which shouldn’t have been put in an exclusively cultural box, but rather in a societal one. Because playing a musical instrument, for instance, is about being in relation with others, and we already know the extraordinary benefits of musical expression on a neural and cognitive level. The Week of Sound was launched for all of these reasons.

It also doesn’t limit itself to France, as several countries have also adopted the Week of Sound…

Yes, it has only grown and grown on an international level, and there are twenty-odd countries now which have a Week of Sound. UNESCO adopted it five years ago with the charter that became the Resolution 39659, which was unanimously adopted by precisely 195 countries. That was a huge victory for us, as it was the first time that sound entered the major concerns of UNESCO. And we are now part of the UNESCO structure, and every country interested in developing the initiative can also organize their Week of Sound.

The theme of this 20th edition is “Savoir écouter, savoir se parler” (“Knowing how to listen, knowing how to talk”). This refers to the valorization of sound, but seems to focus on communication and the societal dimensions sound can have.

Yes. Today, more than ever, we find ourselves in a crisis situation. A societal crisis in which we can observe that people don’t talk to each other anymore. We don’t talk directly and getting someone on the phone nowadays feels like pure luck! Everyone is communicating by text message and it has become the norm to communicate indirectly and out of sync. We currently live in a time when the relationship with the other does not exist in real-time, and we’re losing the notion of the relationship with others. This is regularly analysed by many philosophers and psychoanalysts. It is a complete and utter catastrophe in a relational sense.

Does this mean that people, in your opinion, have become more egocentric?

Absolutely. And not only that, they’re more isolated from one another. They have 100 million friends but in reality have none. And they are not capable of facing a real dialectic with the other.

Communicating with others isn’t always easy, and holding a conversation and maintaining a dialogue is becoming something of a lost art. Now, when people disagree, they break up or become violent. And this is what happens when there is no dialogue, whether it be political – between the political world and social movements – or otherwise. People tense up and can become violent.

The notion of sound is fundamental to human relationships, and because of digital evolution and developments in digital technology, we are now incapable of dialogue. This is a key issue, hence this year’s theme of knowing how to listen and knowing how to talk.

You’ve also been to Mexico talk about the link between sound and violence. Can you tell me more about this?

We organized a Week of Sound in Mexico about the relationship between sound and violence, and how noise can generate violence.

In contrast to the 19th century and 20th century, noise is sonic continuum. There aren’t any cart noises in the street - that’s gone. We have a noise continuum that comes from constant motor sounds, air conditioning on every façade… To put it another way, we have permanent noise. And this noise creates an absence of micro-silences, which means that we don’t have the breathing space to be able to understand the world. This absence of micro-silences puts us in an extremely difficult situation on a nervous level, induces auditory fatigue or even tinnitus and hearing loss. We know that people who live in the city lose their hearing faster than others, and all of this is linked to the sonic ambience that never gives up. I call it “the one sound” which hides micro-noises.

To come back to noise as a generator of violence, the absence of micro-silences means that when a person does not have the capacity to express themselves in a tranquil environment, we don’t have the possibility of listening to others and understanding what goes on. What we say at the UNESCO Week of Sound is that violence prevents people from thinking.

That’s an important element to highlight, as sound has often been used as a catalyst to destabilize…

If you want to kill a population, all you have to do is put people in a state of permanent noise, and you’ll obtain no answers.

Knowing that ears don’t have eyelids, noise can come through the ears without knocking at the door and enters the intimacy of everyone. You enter everyone with sound, whether they like it or not. And you can kill everyone with sound. And as an expert with tribunals and the Cour of cassation in Paris, I have witnessed to what extent people who are subject to a sonic aggression talk of “rape” – they are raped and it reaches to the very depths of their being. We have underestimated all of this. We talk about visuals all the time, but we’ve forgotten that it’s sound that makes us act. When we're in a calm space, we’re relaxed and we can think. Noise prevents that.

Another point is that there is music today that can be heard on all medias, and this music is completely compressed. It is squashed and placed above the noise. So, not only do people have noise around them, but you add an extra level of noise, a musical noise that doesn’t reduce. It’s like a galette that is situated above the background noise of everyday life. And this galette, like noise, does not have any micro-silences: the constant news in the morning, all this aggression on the radio, on streaming services and on today’s albums, for example, means an escalation of noise on top of noise.

At the end of the day, people feel suffocated by this sonic ambience which never empties itself. So what do they do? They become violent, more and more aggressive, or they isolate themselves.

There’s also a resurgence in vinyl and younger generations are clearly becoming aware that the sound quality is better. Vinyl sales have recently surpassed CDs. Does this mean we’re gradually leaving behind MP3s and coming back to sounds which are less compressed? That must be a reason to be cheerful, surely?

Yes, this is an important detail. We’re putting together a Quality Sound label with Universal, which will be launched next year. We’re trying to find and establish parameters so that there is the assurance of sound quality.

And what you’ve said is very important – a lot of youngsters nowadays are coming back to vinyl, and not for the reasons people imagined. People thought it was the material that interested them, but in reality, studies have proven that it's the sound that is of interest to them. Today, we have hyper-compressed sounds and through vinyl, they have realized that there’s music like Pink Floyd and The Beatles where there are micro-noises and micro-silences. They have rediscovered another sound, and that explains this resurgence of the vinyl in people’s habits – young and not so young! There’s an awareness of a sound that is more pleasant to listen to, a sound that isn’t as dense.

But beware – if you have a sound that’s hyper-compressed and you press a vinyl with that sound, it’ll still be compressed. Universal has understood this problem, and this label we’re developing will raise further awareness. It will guarantee a certain quality of listening, as well as the musical expression of the musicians and the absence of hearing loss.

What day-to-day initiatives can we take in order to eliminate these parasitical noises on top of noises, and live better - whether at work or in our private lives?

First of all, awareness. Being aware of all these elements is vital.

Today, the education system should go further in this direction. In France, for example, more should be done. In the UK, music has entered schools a lot more. When you play a musical instrument, you are aware of what is a silence, a nuance, a timbre. There is an issue of not knowing sound in France. And when I plan and build school and college rooms in schools, I am amazed to see that at no point will an auditorium be imagined so that young people can listen to each other together and understand what silence is. I ask for an acoustic treatment in all classrooms.

I ask for the same for train stations. Why are train stations so loud and why is it they're a location where people are aggressive and commit violent acts? Well, if you make the sound atmosphere of train stations interact with people's behaviours in stations, you'll find a very direct correlation.

So, to answer your question, it is vital that acoustics and sounds are thought out upstream of urban planning, and that there is a realization regarding the importance of sound from the very first moments in life.

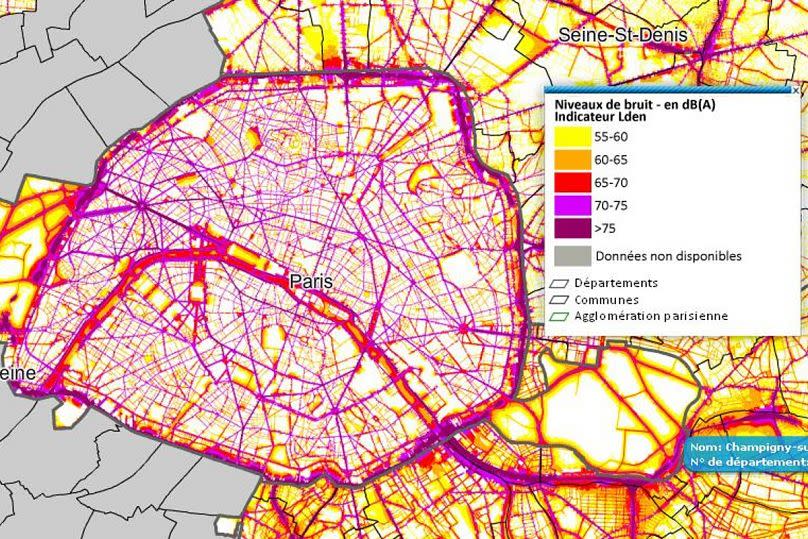

And to go even further, there needs to be an awareness that sonic segregation exists. There’s noise for the poor and silence for the rich. If you were to sound map out the city of Paris, for example, in relation to price per square metre, you’ll find a direct correlation. The most expensive locations are always the calmest. This means that the rich have taken over silence while the poorest stay in noise.

Sound, therefore, takes on a political dimension?

Absolutely. We’re on political terrain here. We need people and politicians to ask themselves whether they want to continue fueling a rich-poor segregation through noise and silence. And it’s not just Paris. When I went to Libya or Beirut or Cairo, the same issue arises. The rich are always in calmer spaces and have silence in order to think and to consider the future of society, whereas the poor no longer have that possibility. It’s an important notion, and once again, that’s why it’s possible to annihilate all velleity if one is plunged in noise.

We’re fully in the political realm when we talk about sound. And segregation and the lack of discussion between people offers an open boulevard for totalitarian states. It’s important that technologies, which are supposed to bring us together and connect us to one another, don’t hinder true communication. We talk, but we don’t talk to each other. New numerical media isolates us and I believe that our governments know it. And that can explain a lot about the things going on in the world.

Are there any countries in Europe or in the rest of the world that have created initiatives or made further progress with regards to sound on a political and cultural level?

Well, everything that I’ve been telling you hasn’t been thought of yet on a collective and international level. What we’re doing now with the Week of Sound is throwing a bomb. A bomb that includes the fact that when we listen to compressed sounds, we ruin not only our ears but also our neurons. Sound and noise are accelerators of neuronic and auditive degeneration. This is being proven.

Regarding all countries, it’s important to put the church at the centre of the village, so to speak, and rethink sound as a trigger for the visual. I’ve said it before, but sound must be a vehicle for the visual and we must stop thinking about the image first and then about sound. I spoke to filmmaker Costa-Gavras and he told me that when he constructs a film, he always crafts it from the sounds. He said that he chooses his actors with their voices and creates a symphony even before the cameras have rolled. Everything has to be constructed before the film, and not afterwards. Claude Lelouche and Jean-Jacques Annaud have the same approach. All of the great directors since Hitchcock work the sound in order to obtain the image, and our daily lives have to correspond with this.

We’re very much in a film, and we have to think about sound to better understand what comes our way. We mustn’t be fooled by what we see, and again, without the awareness of sound, we can’t talk. You can’t say “I love you” on the Champs-Élysées, because we say it at 50-60 decibels and when you’re on the Champs-Élysées, you’re being met with a background noise of 70-80 decibels.

The same could be said about restaurants. There was recently a study that was published, stating that eight out of ten people in France are bothered by the noise in restaurants and choose to leave rather than be subjected to it.

Yes, and we observed it with regards to young people. This surprised us, as 18-24-year-olds leave restaurants too, because they experience the need to talk. So, noise isn’t for the young and silence for those above 50. That’s not the state of things, and there’s a young generation today that is already tired and realizes that if they want to talk with one another, a tranquil space is needed.

What was also said by that study was that people who work in restaurants are frequently exhausted and go on work hiatuses, experience tinnitus and lost their hearing more than others. They too are subjected to a sonic landscape that threatens their hearing. They’re not the only ones too – take flight attendants and the aviation world.

To go back to what you were saying about film directors – you’ve worked with the Cannes Film Festival, is that correct?

Yes. With Cannes director Thierry Frémaux and filmmaker Costa-Gravas, we launched a prize – the Prize for Best Sound Creation – five years ago, in the context of the Un Certain Regard section. It’s about music, obviously, but more about valorizing the artistic and narrative dimension that sound brings about. It was incredible, because it took 70 years for Cannes to have a sound prize.

We develop an intelligence on cinema and film through sound, because every micro-noise imagined by the mixing teams is a vital element in the making of a film and allows the audience to understand the filmmaker’s intentions. We always say: “I’m going to watch a movie.” We should also say: “I’m going to hear a movie.” (Laughs)

Finally, are there any sounds you prefer or noises that disturb you the most in day-to-day life?

Honestly, no. And I’ll tell you why. All sounds are marvellous, because it’s life. Sound is life, and I’ll say something important here and use a phrase from Murray Schafer, who was a great Canadian composer who died not long ago. He said “All the sounds commit suicide and never return.”

Sounds are life and the instant, the present moment. If I want to be myself, if I want to exist in the present moment, I must hear. Really hear. Hearing, listening – that’s existing. Every sound and every noise are welcome. And what we call noise is the sound that we don’t want. If we have someone we dislike, they’ll create noise and not sound.

Sure, there are sounds I dislike, but I leave them where they are. But generally speaking, I like all sounds because they’re our raison d’être and silence doesn’t exist. All silences are inhabited – there’s always something in silence.

If I’m in a conversation with someone like I am with you now, I’m in the present moment – it’s not yesterday or tomorrow, it’s now. And generally, in European society, we have the tendency to forget that sound is the instant. And this is the notion we’re trying to get across on an international level – and it’s without a doubt the right way of listening to others and better understanding what is happening from country to country.

Check out the video above for extra footage and extracts of the interview.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News