US supreme court gives conservatives the blues but what's really going on?

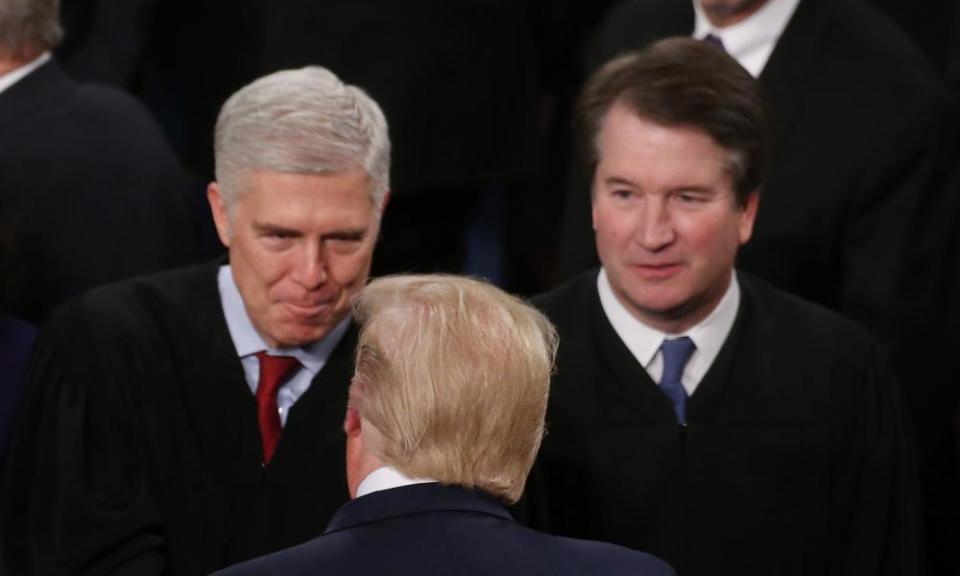

For all the ominous twists of Donald Trump’s presidency, his placement on the US supreme court of two deeply conservative justices, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh, inspired a special kind of foreboding for many liberals.

With three conservatives already sitting on the court, the creation by Trump of a seemingly impregnable, five-vote conservative supreme court majority appeared to pose a generational threat to essential American rights and freedoms.

Related: John Roberts is now supreme court's swing vote – to conservatives' disdain

But as the first full term with the two Trump “supremes” draws to a close, a curious development has taken hold. Last month, the court handed down a trio of rulings that clashed directly with Trump’s agenda on the hot-button issues of abortion, immigration and LGBTQ+ rights – angering the president, tentatively pleasing progressives and leaving many court watchers to scratch their heads.

There never was any doubt about the kind of supreme court that Trump and his sponsors set out to build. But suddenly there is doubt everywhere about how close – or far – their project has come to success.

“I’ve referred to this past month at the supreme court as Blue June,” said Josh Blackman, a conservative court analyst and professor at the South Texas College of Law. “It seems as if almost all the big cases went to the left, and it’s made conservatives blue – that is, sad.”

First Gorsuch wrote an opinion destroying the Trump administration’s argument that a 1964 law prohibiting employment discrimination “because of sex” does not apply to homosexual or transgender employees. “Today, we must decide whether an employer can fire someone simply for being homosexual or transgender,” Gorsuch wrote. “The answer is clear.”

Then Chief Justice John Roberts, a George W Bush appointee, found that the government had failed to make its case for ending a program protecting so-called Dreamers – undocumented immigrants who arrived to the US as children.

“Do you get the impression that the Supreme Court doesn’t like me?” Trump tweeted after the decision was released.

Roberts struck again later in the month, vacating a Louisiana anti-abortion law on the grounds that the supreme court had vacated an identical law in Texas just four years earlier, before the arrival of Gorsuch and Kavanaugh.

Roberts’ defection eliminated the law in a narrow 5-4 ruling.

Daniel Goldberg, legal director at the progressive Alliance For Justice, called the victory on abortion surprising, but not because it demonstrated some unforeseen liberal bent on the part of the justices.

“You know what surprises me, is that it wasn’t 9-0,” said Goldberg. “What does it say that four justices were completely willing to ignore precedent just four years old?

“The response to these decisions just epitomizes how extreme the conservative legal movement is in this country.”

Legal analysts cautioned the recent unexpected rulings were not signs of real moderation, and they said the court had moved unmistakably to the right under Trump.

Gorsuch and Kavanaugh were willing to expose about 700,000 Dreamers to deportation, and both justices argued in favor of upholding the Louisiana abortion law, which was seen as posing an existential threat to the landmark Roe v Wade decision. Even in tipping that case to the left, Roberts emphasized that he was not doing so on the merits.

“He has been consistently not supportive of abortion rights,” said Gillian Metzger, a professor of constitutional law at Columbia University, of Roberts. “I would not read into his decision any signal that, if confronted with a new kind of abortion measure, or even potentially if confronted with an effort to really rethink reproductive rights generally, that Roberts would necessarily be a very sympathetic respondent.”

The court has advanced other conservative causes this term, expanding presidential power and challenging the separation of church and state by releasing public funding for religious schools.

In one case, the four most conservative justices, including Gorsuch and Kavanaugh, ruled in favor of forcibly reopening California churches, against the will of state officials, in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic, so that Christians could celebrate Pentecost. Again, with Roberts’ defection, they were overruled.

Multiple analysts said Trump’s failure, despite having a sympathetic court, to deliver on his promises to dismantle Barack Obama’s healthcare law and roll back abortion rights, could lie partly with flaws in his own administration’s legal strategies.

In a series of cases, Trump lawyers have advanced arguments that Roberts has found to be pretextual or beside the point, as when administration lawyers said they wanted to include a question about citizenship on the US census because they wanted better data to ensure protection of voting rights.

Roberts, whose light touch as the presiding officer in Trump’s impeachment trial just seven months ago was seen as aiding Trump’s expeditious acquittal, doubted the argument. “Reasoned decision-making calls for an explanation for agency action,” he wrote. “What was provided here was more of a distraction.”

A similar objection – not to say exasperation – was detectable in Roberts’ recent ruling to leave in place the Dreamers program. Lawyers defending immigrants in the case said the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was trying to pretend that it might want to keep the program, but its hands were tied because parts of the program had been thrown out in court.

Again, Roberts detected a note of disingenuousness. “An agency must defend its actions based on the reasons it gave when it acted,” he wrote. “This is not the case for cutting corners to allow DHS to rely upon reasons absent from its original decision.”

“You see Roberts much more willing to push back on that side of the Trump administration, and so I would say that’s been a shift,” said Metzger. “Over time the Trump administration is losing a little bit of the benefit of the doubt.”

Rulings remaining in the current term – there are eight outstanding cases – could include powerful conservative decisions that could yet erase any memory of the court’s recent moderation.

Related: Don't be fooled. The US supreme court hasn't suddenly become leftwing | Nathan Robinson

In Trump v Mazars USA, the court is expected to rule on whether financial and accounting firms that have worked with Trump must hand over tax records subpoenaed by Congress, in what analysts say is a major test for the balance of powers in the US system of government.

“Although Trump v Mazars is about the tax records, it’s actually about a more basic constitutional principle, which is whether or not Congress can take meaningful oversight of the executive branch,” said Metzger. “And if Congress cannot do that, then we really are moving much more towards an authoritarian presidential regime.”

Just a few months after the last ruling of the term is issued, a much larger ruling will be handed down, with much broader implications, by some 140 million voters in the November presidential elections.

If Democrat Joe Biden can defeat Trump, he appears likely to have the opportunity to appoint at least two justices, with the octogenarian liberal justices, Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer, nearing retirement. The Democrats would have to win the Senate too to ensure a smooth confirmation process and preserve the court’s current ideological balance.

“If the Democrats have the Senate, I think it’s very likely that Ginsburg retires immediately and Breyer retires the next year, two back-to-back,” said Blackman. “That wouldn’t affect the composition of the court, unless Justice [Clarence] Thomas becomes ill, so I think the court would more or less stay the same for a while.”

But if they win a strong majority, Democrats could attempt to pass reforms to bring the court more in line with the popular will, by adding seats to the court or imposing time limits on justices.

Whatever the election outcome, the last court term of Trump’s first term seems likely to be noted for its unpredictable twists.

“This is a very strange term,” said Blackman. “I don’t remember one quite like it.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News