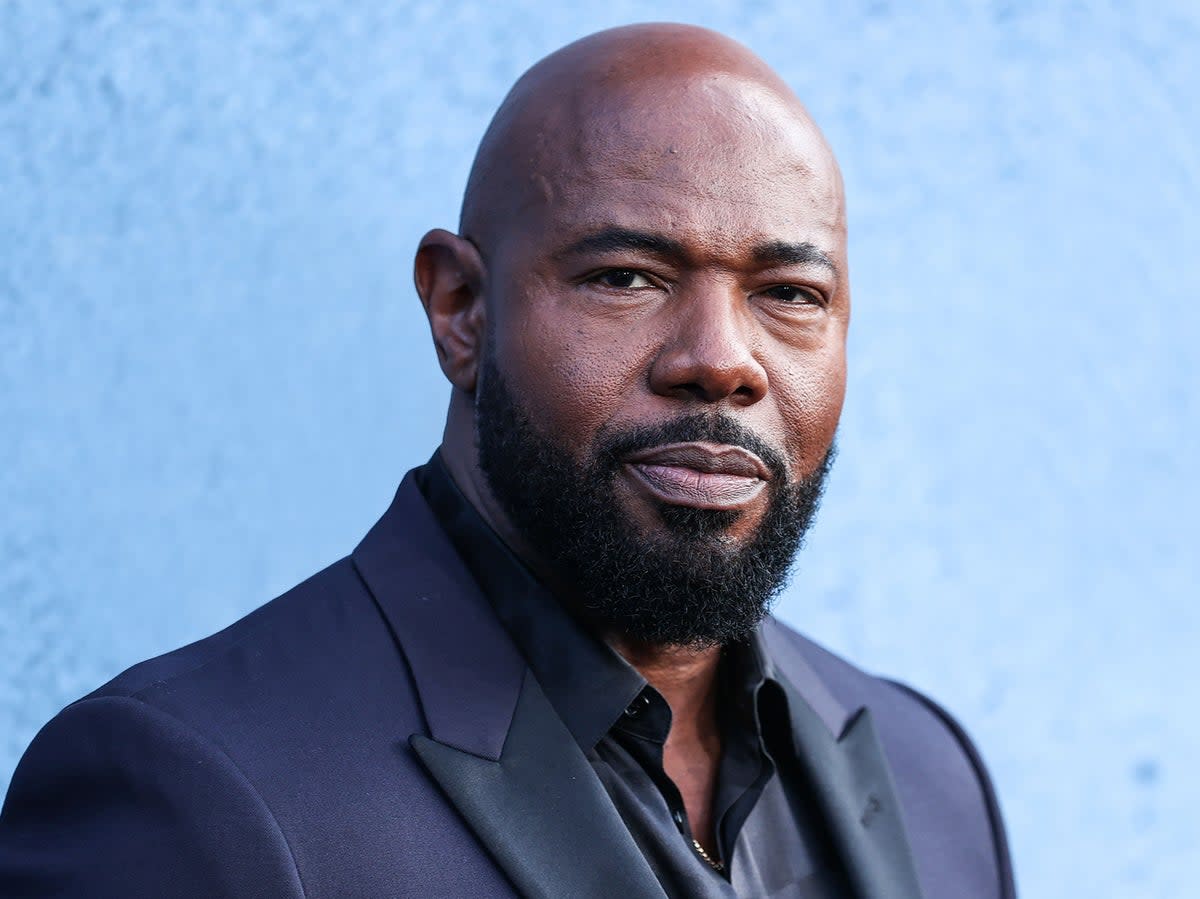

‘I’ve never met anyone like Will Smith’: Emancipation director Antoine Fuqua on his slavery drama and the Oscars fallout

Antoine Fuqua was just a child when he was shot on the streets of Pittsburgh. But the memory is spectacularly vivid. “I was 15,” says the 56-year-old director of the Oscar-winning Training Day. “I remember running through an alleyway and I remember it raining and I remember hearing a voice say ‘run’. I don’t know where it came from. But I remember every detail of those moments. Every detail.”

Hearing Fuqua describe what happened is like watching a sequence from one of his own neo-noir movies. “The bullets hitting the telephone poles. The splintering. The sound,” he says. “The rain on the guy that was shooting. The glasses he wore. The water hitting his glasses. The rifle in his hand.” Each freeze frame comes with a gesture: Fuqua’s hands splayed wide for the bullets, his knuckles gliding past his eyes for the rain, his finger pulling an imaginary trigger. “Then I remember going into a store, and the reality of seeing the blood hitting the floor, and I remember thinking of my family.” He also thought about his funeral, the smell of flowers filling his nostrils. And he thought of God. “Sometimes it’s in your worst moments that you see God,” he says.

Fuqua survived the shooting, of course, and he once called the moment his “big break”, because it got him off the streets and into the cinema. And the faith he found in that near-death moment has become the lifeblood of all his films, perhaps most prominently in his electric 2001 crime thriller Training Day, in which the world is divided into wolves and sheep. Denzel Washington won a Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of corrupt, lupine LAPD narcotics officer Alonzo Harris, who commits a heinous litany of crimes, all while wearing a chunky crucifix round his neck. The first note that Washington – a frequent collaborator of Fuqua’s and a devout Christian – made on his script was a line from the Bible: “For the wages of sin is death.” Fuqua’s subsequent movies, from the historical adventure King Arthur and the sports drama Southpaw, to the western The Magnificent Seven and the films in the Equalizer vigilante franchise, all allude to religion. And in his new film, the beautiful, brutal Emancipation, faith is a vital part of what keeps Will Smith’s character, a slave on the run, alive.

“If the heart of the movie is love and faith, I’m interested,” murmurs Fuqua in his deep timbre. He is sitting on an armchair in the centre of a London hotel room, a picture of elegance and serenity in a black suit, night-navy polo neck and a pair of Derby shoes as sleek as Alonzo’s Chevy Monte Carlo. “I wouldn’t be sitting here talking to you if there wasn’t a God or something bigger than me.”

Ethan Hawke, who co-starred in Training Day as a doe-eyed rookie who gets caught up in Alonzo’s twisted antics, once said that he sees all of Fuqua’s films as “a collective scream against authority”. Fuqua nods. “Ethan’s right. It comes out subconsciously. They all come back to injustice, to people being stepped on and mistreated. I grew up in a tougher area, so I saw it happening to my parents. People taking advantage. I don’t like that at all. Whether it’s an authority or a bully. I don’t like bullies.”

Emancipation is full of the worst kind of bullies. It is inspired by the story behind the 1863 image of “Whipped Peter”, which exposed the horrific cruelty of American slavery, and became a defining picture for the abolitionist cause. Smith plays the escaped slave in the photograph who was depicted with his back – riddled with keloid scars from relentless lashings – to the camera. Smith disappears into the role. We no longer see him as a movie star; he’s a man on a mission for freedom in the American civil war. He stares defiantly in the face of snarling dogs and spitting slave owners, wades through swamps and fights alligators on his way to Lincoln’s army in Baton Rouge. At times, several minutes go by without any dialogue, moments where Smith is more powerful still, his jaw clenched and eyes hard. In his first film after the Oscars slap, he exquisitely captures the dignity we see in Peter in the photograph, his chin held high.

“Will has a lot of dignity,” says Fuqua. “He is a great human being. I’ve never met anyone like him.” The director was taken aback when he saw Smith smack Chris Rock on stage at the Academy Awards in March, after the comedian made a joke about Jada Pinkett Smith’s shaved head. “I was shocked,” he says, “because that’s not the Will I know. But there’s a lot of pressure in everyone’s lives. It’s tough, sometimes, being a celebrity like that. Sometimes the human comes out and it doesn’t come out the right way. I hope that Will and Chris can find some peace there. They’re good people, they are. They’re not bad people at all… and it’s a struggle, right? There’s no perfect human being. Will was extremely regretful. I spoke to him afterwards and he was in tears. He was just hurting, you know? We have to be careful. It’s nice to joke about each other but sometimes we, all of us, have to be a little more sensitive.”

Pinkett Smith suffers from alopecia, and Fuqua says he can relate to the strong emotions around hair loss. “I know this wasn’t what Jada had, but I had someone in my life go through cancer recently,” he says. “They lose all their hair and a lot of things happen, and sometimes if you don’t know that and you make a joke about that it can hurt deeper than you can possibly know. Celebrities have the same issues a lot of other folks have. They go through their own mental, personal tortures that you never see.”

After the confrontation at the Academy Awards, Washington was seen rushing to Smith’s side. Later, speaking through tears as he received his Best Actor Oscar for King Richard, Smith revealed what Washington had told him: “At your highest moment, be careful, that’s when the devil comes for you.” “It was perfect that Denzel would go and try to wrap his arms around Will and give him some words of wisdom,” says Fuqua, making a hugging gesture with his broad hands. “That’s who Denzel is. We talk about faith a lot when we’re together. More than anything else.”

Fuqua certainly needed a little faith during the making of Emancipation. The film’s production was plagued with problems from the start. It was originally meant to be shot in Georgia, but moved to Louisiana in protest against the state’s restrictive voting laws, which primarily affected communities of colour. Then, Hurricane Ida hit, devastating the area and delaying the shoot further. It was also filmed under strict Covid restrictions in 2021, and it was pushing 40 degrees every day. “I’m still recovering,” says Fuqua, with a very small laugh. “I have PTSD talking to you about it. It was supposed to be a four-month shoot and we wound up shooting for eight months. Apple had to have ice jackets brought in for everyone, to cool down. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done. Anything that could be thrown at us was thrown at us. I had my trailer burned down one night, while I was filming on a real plantation.” How did that happen? “Yeah. Exactly,” he says, with a sad, knowing look. He seems to have his own theories. “It was really tough.”

I’m only scratching the surface of the ugliness of slavery

The film’s subject matter took its toll on Fuqua and the cast; he says he was close to tears much of the time and had to take a shower immediately after shooting every day. “I felt just horrible,” he says. “Had to wash it off. But we had therapy for everyone. And it was the crew and the Black and white actors that kept me going. After the hurricane, a lot of people [working on the film] were homeless and they still showed up every day to work. When you see that humanity come together to help tell a story, it gets you through it.”

The film, like all of Fuqua’s work, is packed with relentless, traumatic violence. One slave’s legs are ripped to shreds by a dog. Another’s cheek is branded, while the heads of escapees loom over the Confederate camps on stakes. “I don’t think you can flinch on violence when telling a story about slavery,” he says. “There’s no PG-13 in that. But I also didn’t want it to be exploitative – these are all facts. There’s a great saying, I think it was Maya Angelou, she said, ‘Not knowing is hard. Knowing is harder.’ The more I dug into slavery, I couldn’t even scratch the surface of the ugliness of it.” In Emancipation, Fuqua has created a place resembling hell on Earth – Confederate camps where men, both Black and white, lose their limbs from disease and mass graves are overflowing, bodies turning putrid in the hot sun.

Fuqua also believes that showing the violence is important, in order to stop history from repeating itself. The morning we speak, Kanye West has been banned from Twitter for posting an image of a swastika inside a Star of David. Fuqua has been following the rapper’s latest comments about Hitler, and remembers when he said, in 2018, that slavery sounded like it was “a choice”. “I just hope he can get the help he needs,” says Fuqua of the artist, who has bipolar disorder. “‘Four-hundred years of slavery is a choice’ is a ridiculous thing to say. I don’t know why he would say that. It’s just not possible. What human being would want to be in bondage and have their family ripped away from them and treated like less than an animal?” Such experiences remain incredibly difficult to process, which is why Fuqua wanted to create a sense of disorientation right from the film’s first moment. In the opening scene, a sweeping aerial shot over the swamps makes 1860s Louisiana look like another planet. “Watching it, you could be on Mars,” he says, gesturing into the ether. “And yet this is our world. This is what we have done, not very long ago, to each other.”

’Emancipation’ is out in cinemas and on Apple TV+ on Friday 9 December

Yahoo News

Yahoo News