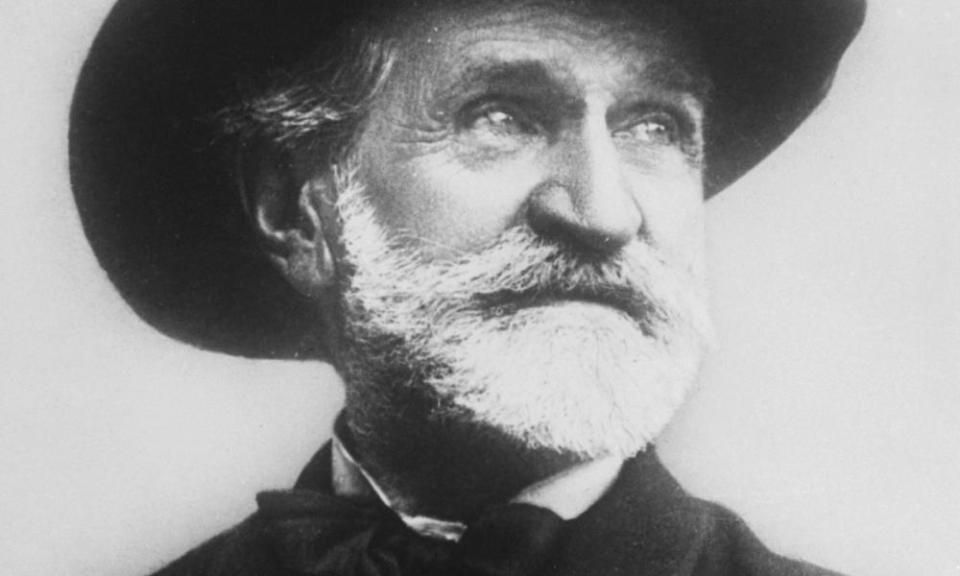

Verdi: where to start with his music

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) is one of the greatest opera composers, and arguably the most popular of all. His name is synonymous with the history of Italian music in the second half of the 19th century, his work is central to the repertory of every opera house in the world. He is sometimes compared with Shakespeare, whom he adored, though he spoke little English and knew the Bard’s work only in translation.

The music you might recognise

Verdi was an outstanding melodist, and some of his arias and choruses – such as La Donna è Mobile from Rigoletto, La Traviata’s Brindisi (the drinking song) and the Anvil Chorus from Il Trovatore – are familiar to millions. In Italy, the Chorus of Hebrew Slaves from Nabucco has long been associated with national unity and solidarity. The Grand March from Aida, meanwhile, has become a staple of the brass band repertory and is sometimes used at weddings, and Verdi’s music can be heard on the soundtracks of films from Zack Snyder’s 300, Claude Berri’s Manon des Sources to Luchino Visconti’s Senso, it has advertised lager, jeans and pasta sauce. It even features in the video game Grand Theft Auto.

His life …

The son of an innkeeper, Verdi was born in Le Roncole, near Parma, and went to school in nearby Busseto, where his talent was noticed by Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant, who oversaw his early musical education. At 18 he was rejected by the Milan conservatory, but remained in the city (at Barezzi’s expense) to study privately. His first opera, Oberto, was well received at its La Scala premiere in 1839, and the theatre’s manager, Bartolomeo Merelli, wanted more. Un Giorno di Regno was a fiasco the following year, however. Verdi’s discouragement, combined with depression at the death of his first wife, almost made him abandon composition, though his third opera, Nabucco, undertaken at Merelli’s insistence, made him famous overnight.

Related: Beethoven: where to start with his music

He called the period that followed his “galley years,” during which he composed an opera roughly every eight months, and the best of his early works have a clamorous vitality that continues to enthral. Ernani (1844) is a rip-roaring thriller. Macbeth (1847, revised in 1861) was the first of his Shakespearean operas. By 1847, he had become so well known internationally that there were premieres in London (I Masnadieri) and Paris (Jérusalem, a reworking of the earlier I Lombardi).

Between 1851 and 1853 he composed three masterpieces, Rigoletto, Il Trovatore and La Traviata, which remain among his most popular operas. They were not, however, without controversy in their day. Verdi spent much of his career struggling to get his work past the censors, who frequently raised objections on political or moral grounds, and he had to make substantial changes to the text of Rigoletto, based on a play by Victor Hugo, banned as both inflammatory and obscene, before it was permitted on stage. The realism of La Traviata, with its courtesan heroine and contemporary setting, caused consternation, and throughout Verdi’s lifetime the opera was usually staged set in the 18th century.

Busseto and its environs remained his home for much of his life. With success came affluence, and in 1851 he moved with his partner, the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, into a new villa where he lived until the end of his life. He and Giuseppina, although in a relationship since 1847, did not marry until 1859. Local opposition to their unmarried status colours Verdi’s depiction of Giorgio Germont’s disapproval of his son’s affair with Violetta in La Traviata.

… and times

When Verdi was born, Italy was a divided nation, made up of small individual states under Austrian or French occupation. Opinions differ as to how much he intended his early work as a demand for liberation and unification, but, beginning with Nabucco, with its Chorus of Hebrew Slaves mourning the loss of their country, his operas became the focus of the nationalist aspirations of the Risorgimento. In 1859, two years before the proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, “Viva Verdi” became an acronym for “Viva Vittorio Emmanuele, Re D’Italia,” and in 1861, the composer briefly served in the newly formed Italian parliament.

Though a man of the theatre, he lived in an era of great novelists and his depth of characterisation and the social concerns of many of his operas find parallels in the works of Dickens, Balzac, George Eliot and Flaubert, among others. Marcel Proust hugely admired La Traviata, writing that Verdi had transformed what he considered to be indifferent source material, the novel and play La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas fils, into truly great art.

Why his music still matters

After La Traviata, Verdi’s output slowed, and his operas became larger in scale. His operas from Simon Boccanegra (1857) to Aida (1871) are concerned with power, organised religion and freedom. The mix of comedy and tragedy in Un Ballo in Maschera (1859) and the fatalism and edgy humour of La Forza del Destino (1862) reveal a debt to Shakespearean dramaturgy. Don Carlos (written in French for Paris in 1867, then revised in Italian as Don Carlo) constitutes his most profound analysis of how the powers of church and state conspire to destroy the individual, while behind the orientalism of Aida lurks a depiction of life in a theocracy on a war footing. Verdi’s ambivalence towards religion ran deep, and informs the ambiguities of his Requiem, written in 1873 as a memorial to the Risorgimento writer Alessandro Manzoni. Evoking humanity’s response to the terrifying majesty of God, it ends in a numbed void with the endless reiteration of the words Libera Me (“Set me free”).

After the Requiem, Verdi ostensibly retired from public life, though this was by no means the end of his career. His publisher, Giulio Ricordi, engineered a collaboration with writer-composer Arrigo Boito, which resulted first in a major revision of Simon Boccanegra, unsuccessful at its first performance, then in Otello and Falstaff, premiered in 1887 and 1893 respectively. A score of remarkable power, Otello is for many the greatest of all operatic adaptations of Shakespearean tragedy. Falstaff, based on The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, is widely regarded as Verdi’s farewell to the stage, a bittersweet comedy that looks back on life with humour as well as sadness, before resolving its tensions in a fugue that asserts that “Everything in the world is a joke.”

There are no stereotypical heroes and villains in his operas, only people, with their strengths and fallibilities

Verdi was a constant innovator and there is an immense stylistic difference between Falstaff and his early works. He effectively re-wrote the history of Italian opera by first perfecting and then dismantling the bel canto traditions he inherited from his predecessors Bellini and Donizetti – the formal patterns that subdivided arias and scenes into slow and fast sections, separated by recitative or linking passages.

Traditional structures still underlie the great operas of the early 1850s. From Simon Boccanegra onwards, Verdi increasingly pushes at the limits of form in a quest for dramatic intensity and psychological veracity, though we are still aware of structural demarcations between arias, choruses and ensembles. But in Otello and Falstaff, traditional formal boundaries are dissolved. Recitatives, arias and ensembles flow seamlessly into one another, each act unfolds in a single unbroken musical span. Comparisons were (and still are) made with Wagner’s methodology of through-composing each act, though Verdi profoundly distrusted Wagner’s symphonic method with its ceaseless thematic elaboration.

Yet the reason why Verdi matters ultimately lies, perhaps, beyond musicological considerations and can be found, I suspect, in his profound assertion of our common humanity, captured and expressed in the visceral thrill of the singing voice in full flood. From Rigoletto onwards there are no stereotypical heroes and villains in his operas, only people, portrayed with all their strengths and fallibilities, and their potential for both greatness and evil. Again it is a standpoint that places him in opposition to Wagner, his exact contemporary (they were born the same year), the great myth maker, who creates, destroys and redeems worlds, where Verdi celebrates existence by compassionately accepting and exploring life in all its variety.

Great performers

Singers and conductors have long been drawn to Verdi. All of his operas have been recorded, many of them multiple times, sometimes deploying different editions that Verdi prepared in his lifetime, or making standard theatrical cuts. As far as conductors are concerned, Toscanini, Claudio Abbado and Herbert von Karajan are by turns thrilling and passionate, though you need Victor de Sabata or Carlo Maria Giulini for the Requiem, and Don Carlos is probably best served by Antonio Pappano in French and Georg Solti in Italian. For many, Leontyne Price is the greatest of all Verdi sopranos, and is unmissable in all her recordings of his music. Major interpreters of his work, are almost too many to list, but among them should perhaps be mentioned Maria Callas, Renata Tebaldi, Grace Bumbry, Carlo Bergonzi, Franco Corelli, Ettore Bastianini, Tito Gobbi and Nicolai Ghiaurov.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News