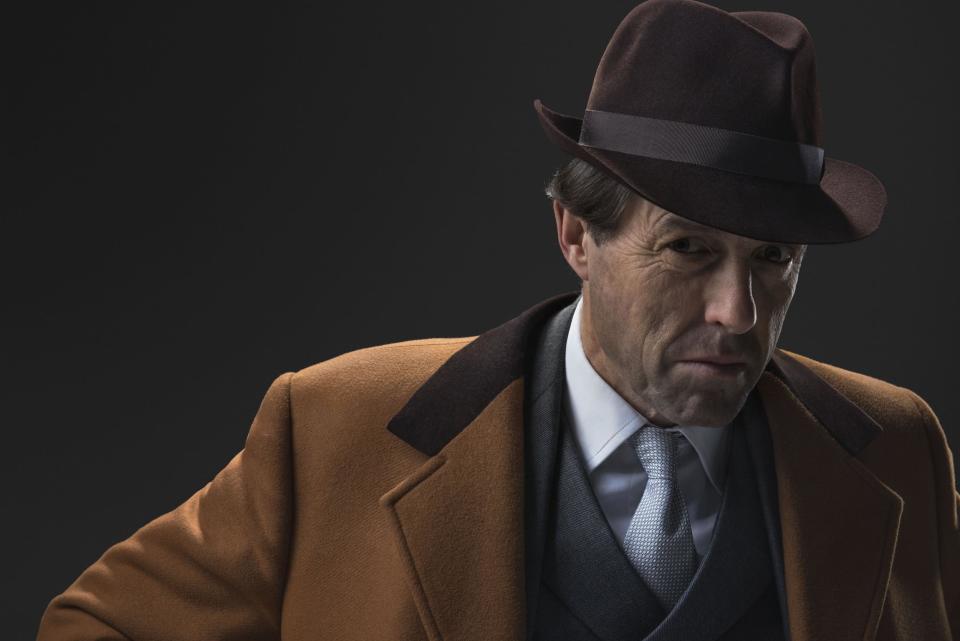

A Very English Scandal, episode 3 review: Hugh Grant has given a Bafta-worthy performance as Jeremy Thorpe

Having lived through a dramatised version of the real life of Norman Scott, the one-time male model who, it was alleged, the leader of the Liberal Party plotted to murder, it was a pleasant little surprise to see some contemporary footage of the real Scott at the end of A Very English Scandal, rather than Ben Whishaw’s rendering of this remarkable man. An enigmatic smile playing around those full lips – even at pushing 80 you can appreciate the allure Scott possessed in his youth – it was confirmed that he is alive and well, living with 11 dogs (and dogs were quite a big part of this story), and still hasn’t recovered his National Insurance card.

This document, by the way, was the means by which you could gain legitimate employment and benefits in the years before computers came along. Scott maintained that Thorpe had retained a replacement card, and would not release it back to him. Therefore, Scott was always out of work, short of money, and always going to be trouble for Thorpe.

The national insurance card fiasco ensured this quite superb production was maintained right to the end, and the drama and suspense with it. I especially relished the forensic attention to period detail – the authentic Hoovers, the Austin Allegro police car, the disco music – Gonzalez (“Haven’t Stopped Dancing Yet”), Amii Stewart (“Knock on Wood”) – people smoking on the bus, and the BBC Radio 2 jingle. It took me back, I must say.

But what was clearly missing, for the sake of symmetry if nothing else, was some indication of the health and/or whereabouts of Scott’s alleged assassin – Andrew “Gino” Newton. This extraordinary figure, played with a sort of Eric Idle idiocy by Blake Harrison, according to Gwent Police had been dead for some time. However, subsequent reports indicate that he’s merely changed his name and lain low. Police have now reopened a probe into the scandal and the development has become subject to intense speculation. (The new investigation was prompted by the evidence of Tom Mangold in a previously unseen Panorama programme from the era.)

However, when all’s said and done, Newton was granted crown immunity from prosecution in return for giving evidence at the 1979 trial of the four coconspirators including Thorpe. A run-in between Scott and Newton is a tantalising though unlikely prospect.

Of course, like all biopics of famous historic personalities, we know how it all ends, though in the case of Jeremy Thorpe, the great establishment figure who endured such a painful fall from grace, much of the detail may have been forgotten, or, indeed, unknown to younger generations. After all, most of the rest of the people involved are dead, and no one under the age of 50 can remember the events firsthand. It was, even so, a massive story.

To borrow the expressions used by Thorpe’s barrister at his trial (for incitement to murder and conspiracy to murder), George Carman QC (played with huge, bustling style by Adrian Scarborough), of all the “bastards, liars, perverts, thieves, blackmailers, inbreds and arsonists” to make their way into the House of Commons, it was the Right Honourable Jeremy Thorpe who had the greatest of criminal charges levelled against him – an achievement of sorts.

Scott made an extremely brave and surprisingly credible witness. When he told the court that “Jeremy Thorpe lives on a knife-edge of danger” he summed up the entire scandal. There was much evidence against Thorpe about both the original homosexual and illicit relationship with Scott, and the subsequent events that were to end with a great dane, Rinka, being cared for by Scott, shot dead on the edge of Exmoor, on the dark rainy night of 23 October 1975.

Much of the script was based on documents, memoirs and the trial transcript, complete with its explicit references to anal penetration, Vaseline and “biting the pillow”.

Yet I wondered how fanciful some parts were. The conversation between Thorpe and his second wife, Marion, for example, over a supper of cod in parsley sauce (all the rage in the late 1970s). So the choice of dish was believable, but how much did he tell her about his prior sex life and affair with the man nicknamed “bunny”? Was there some wary chat with Carman about bisexuality, and how you could get beaten up after picking up random guys? I’m not sure Thorpe’s possessive and domineering mother Ursula, devoted to him but sharp-tongued with it, really did say to him after his acquittal: “Of course, you’re ruined. You know that, don’t you?”

Clever as Carman was, the reason Thorpe got off was the disgracefully loaded summing up to the jury delivered by Mr Justice Cantley. The drama’s producers cleverly included at the end a little clip of the “Biased Judge Sketch” by Peter Cook (catch it on YouTube), which was inspired by the case, one of the finest ever examples of British satire: “And now you must retire to consider your verdict of not guilty”.

Thorpe was diagnosed with Parkinson’s in the 1980s, and would live until 2014. The drama, however, and his public life, ended in 1979, fittingly. Thorpe was then still only 50.

Thorpe lived for far longer than the doctors gave him, he survived his political and judicial crises far more easily than anyone thought possible, and, as we witnessed in the earlier episodes, he scaled British politics much more successfully than seemed likely. In 1959 he was elected a Liberal MP for North Devon; by 1974 he had almost broken the mould of British politics and made it to the cabinet.

Thorpe would have hated this drama, though, in that vain, sneaky way of his, been secretly highly flattered by Hugh Grant’s superlative capture of his personality, with the inevitable Bafta to follow. A Very English Scandal, then, and despite its sympathy towards Scott, can be counted yet another, albeit pyrrhic, victory for Jeremy Thorpe.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News