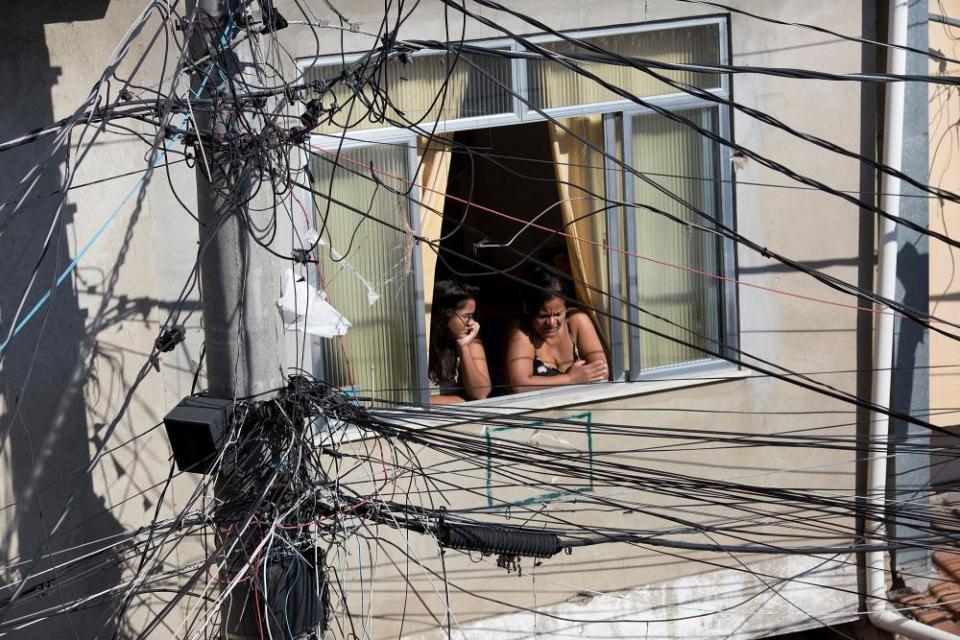

View from the Rio favelas: ‘We're fighting for life while seeking peace’ | Thaís Cavalcante

One year after all eyes were on the “marvellous city”, we are reinventing ourselves amid the crisis in the economy, violence and popular power.

The Olympic Games determined what the quality of life in favelas would be. We are already feeling the impact of the huge amounts of money spent on the games.

The conversations I hear most are about the economic crisis and everyday violence. Most people are concerned about public health services – getting access to free medicines and emergency treatment, while hospitals are threatened with closure. This is one of our greatest needs. We have to fight for our lives, living with violence and hoping for good health, since the healthcare available is either basic or non-existent. We still don’t have what is most important: peace.

More spending is always needed, but it is not always directed to the right place. Part of the money used to make the largest popular party in the world – the carnival – was cut by the city hall, from 24m reais (£5m) to 13m. Rio’s mayor, Marcelo Crivella, says it is to invest in private day care centres, which are subcontracted by the municipal department of education. Many of these are in communities that have deserved greater attention from the authorities.

There has been much discussion about the damage the cut will cause to the economy, tourism and even employment. One of the Maré favela’s carnival blocks [street bands] paraded this year without any financial or institutional support. Apart from the carnival being fun and reaffirming our culture, it is also an instrument of political struggle, and its song lyrics include subjects such as removals, mega events and police violence. In Rio’s favelas, more than 40 carnival blocks paraded –none were part of the municipality’s official carnival calendar and therefore didn’t use any public money. We would welcome funding, but we don’t need it for our parties to function.

Other events repeat themselves, like the military occupation. Since the end of July, we have had federal troops on the streets. They are circulating in the city’s south zone and along the main avenues, bringing “security” and ensuring respectable behaviour. Now, people who live outside of favelas are sharing our experience of three years ago, when Maré was under military occupation, with tanks soldiers, for almost a year and a half. This action cost 600m reais (£146m), more than the amount invested in social programmes in Maré over seven years.

The Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) in Maré is no longer expected to be deployed. The authorities have realised this type of security does not work in the favelas – or elsewhere in the city. We want investments in projects that will increase our prospects in life, in society and in our futures. Meanwhile, Maré is still violent, and things aren’t getting any better.

Amid the public safety crisis in Rio, 10,000 soldiers will remain on the streets until December to reduce theft.

The decree was signed by President Michel Temer, who has the lowest approval rating for a president since 1989. He encouraged the impeachment of Dilma Rousseff in 2016. He also announced an increase in taxes on fuels and wants to implement pension reforms, with new rules for workers: you have to work 49 years with a formal contract to receive the retirement benefit. My mother has worked her whole life in the countryside and is over 60. Her informal work cannot be proven and the situation of many workers from Maré is the same. They will need to work in their old age to guarantee their livelihood. With unemployment reaching 13.5 million people, informal work is growing.

To help with increasing unemployment, projects such as Maré de Sabores offer workshops encouraging women’s empowerment and training residents of Maré in social entrepreneurship.

It is good to see how local development can move the economy. In Maré alone, enterprises have created more than 9,000 jobs, according to the 2014 Census of Maré Entrepreneurship. This does not meet all our needs, but it is an important tool for innovation and reinvention. Here, entrepreneurship is exactly that: creating services based on need and self-taught knowledge, be it as a seamstress, shoemaker, cook, salesperson or any other professional.

Our new rulers do not seem to offer short-term solutions to the people. With all the ongoing investigations, one of the challenges is to keep public services running with less investment. In the midst of all this, I realise how important we are to economic and social power. We’re an important part of the city and the favelas. There are more than 11 million people living in favelas in Brazil, fighting for life while seeking peace.

In the words of Rio-based rap duo Cidinho e Doca: “Eu só quero é ser feliz/Andar tranquilamente na favela onde eu nasci/E poder me orgulhar/E ter a consciência que pobre tem seu lugar...”

[“I just want to be happy/To walk quietly in the favela where I was born/And to be proud/And to know that the poor have a place...”]

Yahoo News

Yahoo News