With virus, US higher education may face existential moment

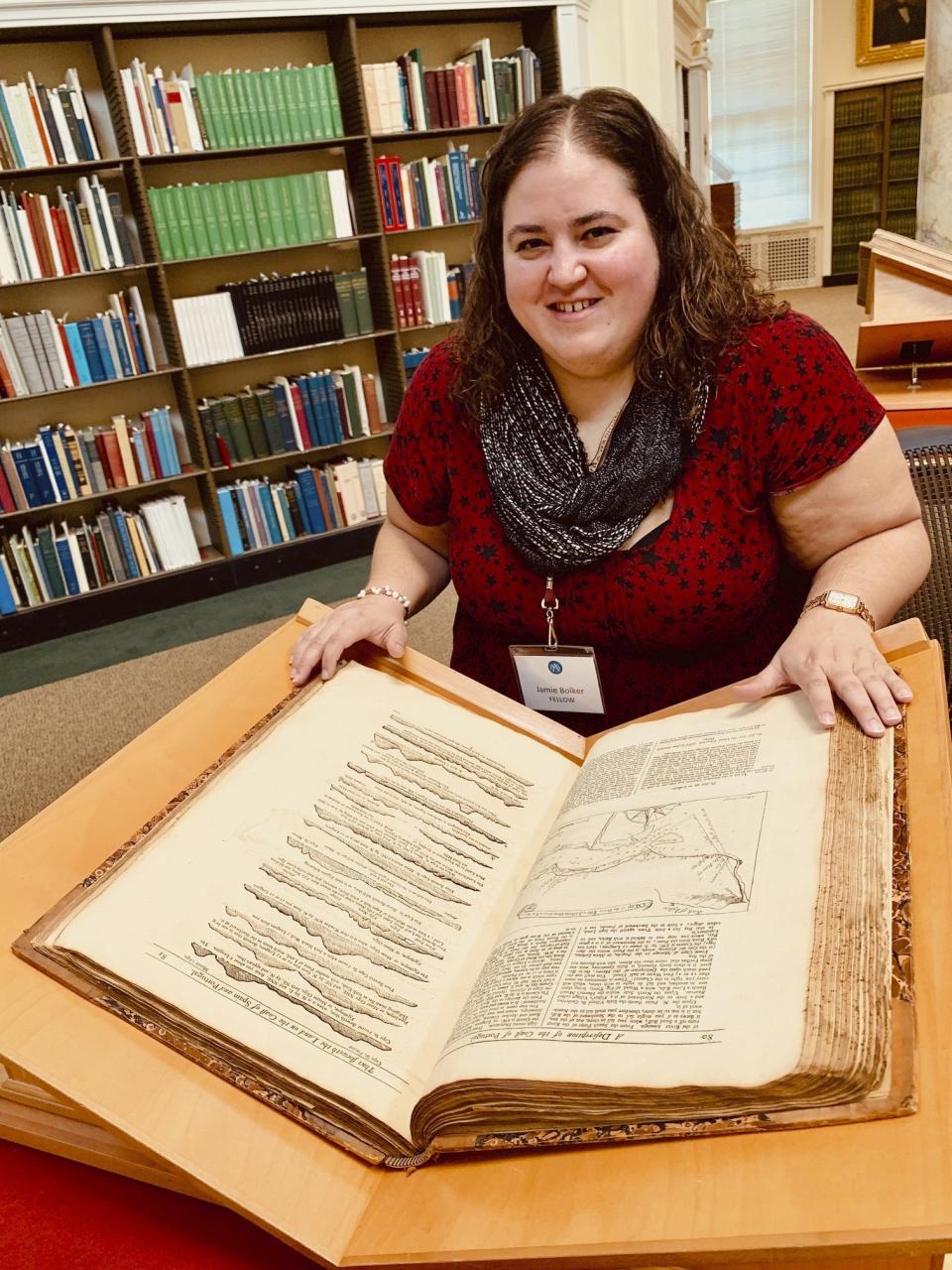

CHICAGO (AP) — When Jamie Bolker started teaching composition at MacMurray College in January, she felt she'd won the lottery. After sending out more than 140 resumes, she had a tenure-track position in English.

Last month, though, Bolker delivered a dire Twitter announcement: “Welp. MacMurray College is permanently closing ... They were already on the edge and coronavirus was the final nail.”

While the Jacksonville, Illinois, school’s financial troubles were years in the making — fueled by declining enrollment, an inadequate endowment and competition — MacMurray spokesman James Prescott said the challenge of securing funding during or after the economically crippling pandemic helped seal its fate.

The dramatic and widespread fallout from the COVID-19 virus has thrown the U.S. higher education system into a state of turmoil with fears that it could transform into an existential moment for the time-honored American tradition of high school graduates heading off to college.

“What every college and university is facing is an immediate cash flow crisis,” says Terry Hartle, senior vice president of the American Council on Education. ”We’re dealing with something completely unprecedented in modern history. There is just so much ambiguity how this will continue to evolve.”

Across America, campuses have become ghost towns, graduation ceremonies have been canceled and school administrators watch as the pandemic rips through budgets, costing billions of dollars in refunded room and board. Some students are seeking partial repayment of their tuition, arguing that online classes can't compare to campus learning. Hiring freezes have been imposed at some schools, and laid-off professors such as Bolker face difficult job prospects.

Colleges, Hartle says, operate very much like businesses: "If there are no customers, there's no revenue and layoffs become inevitable.”

School budgets will inevitably be slashed, with painful ripples. The University of Arizona, which could lose more than $250 million, recently announced plans for furloughs and pay cuts for almost all its 15,000 employees to save $93 million from mid-May through June 2021.

Endowments have crashed in value with the stock market, and there are worries fall enrollment could plummet. Predictions abound that smaller universities already on the financial brink could permanently close. Even larger universities considered financially healthy worry about potential state budget cuts and don't know when they will be able to reopen campuses to new and returning students.

Boston University recently warned that students might not return to campus until January and many colleges — including Harvard University and the University of California, Berkeley — have already moved summer courses online. Purdue University, meanwhile, hopes to reopen on campus this fall; the Indiana school has a task force exploring strategies, including pre-testing students before they arrive and spreading out classes over times and days to reduce their size.

Writing in The New York Times, Brown University President Christina Paxson said reopening campuses this fall “should be a national priority." She noted that higher education employs about 3 million people and the 2017-18 school year poured more than $600 billion into the national gross domestic product.

Schools already are facing staggering losses. They'll have to refund $7.8 billion in room and board for the current school year, according to Hartle's group, which made its estimate based on Department Education statistics. For the University of Wisconsin, which has 11 campuses, he says that will mean returning $78 million.

That doesn’t include losses that can be easily overlooked. One giant urban university, Hartle says, routinely collects $4 million a month in parking lot revenues.

How the schools rebound is about more than money. Before they reopen, administrators must be confident students will be safe in dormitories, close-quarter settings that Hartle likens to “land-locked cruise ships.” Timing is critical.

Some prospective students have already decided on gap years starting this fall. Colleges worry that enrolled students will forgo returning if the virus prevents reopening classrooms, because students may not want to pay for online education after deciding to shell out heavy costs and rack up debt for on-campus experiences.

And with millions out of work, parents who have lost jobs or seen savings evaporate may reduce the number of families who can afford college.

Some students have seen opportunities simply disappear. Savion Johnson was set to transfer this fall from a junior college in California to Notre Dame de Namur University in the San Francisco Bay Area as a Division 2 basketball recruit.

As the virus spread, Johnson received a text from the basketball coach rescinding his offer. The school, immersed in deep financial problems amid dwindling enrollment, decided to cancel the incoming freshman class and competitive sports as it tries to avert total closure.

“I was more shocked than anything. Blindsided,” said Johnson, who started a new college search in March and tweeted this week that he was “blessed to receive an offer from Benedictine University at Mesa" in suburban Phoenix.

The San Francisco Art Institute, the oldest art college west of the Mississippi, announced in March it won’t accept students for the fall, encouraged students not graduating this year to transfer and warned of staff layoffs. Merger talks with other institutions hit an impasse “in no small measure due to the unanticipated hardships and uncertainty" from COVID-19, President Gordon Knox said.

These developments happened shortly after Moody's Investor's Service downgraded its outlook for higher education from stable to negative. It said the financial chaos from the outbreak “could drive states to reallocate funding to other high-need impacted areas, such as health care, reducing available support for public higher education.”

States are “trying to plan in an environment that almost defies planning," says Joni Finney, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Institute for Research on Higher Education.

After the Great Recession ended in 2009, colleges and universities shifted more costs to students and their families. Public higher education in 27 states gets more revenue from tuition than from state funding, according to a 2019 report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. “My concern is we do it in a way that doesn't multiply the hurt on low- and middle-income families as we've already been doing since 2008," Finney says.

Robert Zemksy, a professor of education at the University of Pennsylvania, says schools will be working on a tight deadline as critical decisions have to be made by August.

Colleges at greatest risk for closure, he says, tend to be small, rural schools in the Midwest, Great Plains and the Northeast with enrollments of less than 1,000 and without an excess number of applicants. They represent about 10 percent of schools but just about 2 percent of enrollment nationwide.

The colleges that might fare best and even increase enrollment if classes resume, he says, are state schools such as the University of Illinois and Michigan State University. “People will be looking for security," Zemsky said. “They think that no matter what happens, the schools will stay in business.”

The worst-case scenario: Conditions become so bleak that public colleges shut their doors, leaving students and parents to wonder “if any place could go under at any time,” says Brendan Cantwell, an educational administration professor at Michigan State University

“If we see sudden public closures," he says, “that will be a sign that this is really an event, a time period that is existential."

___

Clendenning reported from Phoenix. Associated Press writer Justin Myers in Chicago, contributed to this report.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News