Visionary or cultural appropriator? Revisiting Bitches Brew artist Mati Klarwein

Mati Klarwein is the most famous painter you’ve never heard of. But if you’re a Miles Davis or Jimi Hendrix fan, the psychedelic rhythm in his paintings will definitely stir a sense of deja vu.

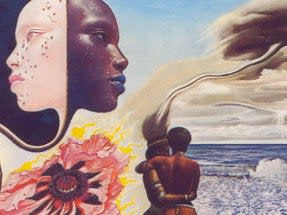

In the Seventies, he blew music lovers’ minds with phantasmagorical album sleeves for Santana, Hendrix and The Last Poets. But his masterpiece adorns Miles Davis’s ground-breaking 1970 album Bitches Brew, which turned 50 this year. Klarwein’s cover art captures the same energy and controversy as the album; distilling it into potent symbolism, surreality and colourful confusion. Bold black figures stare at the ocean as the curls of a female figure’s hair evaporate into the sweeping soft clouds… It is as otherworldly as the 20-minute introductory song, “Pharaoh’s Dance”.

The album illustration celebrates shared experience as well as individual perspectives. Isn’t this what jazz music has long since been rooted in? Jazz, admittedly a broad genre with many variants and iterations, is about how disparate components can fuse together, with ever more intensity when fuelled with creativity, nonsense, and imagination. The imagery is at odds; contrasting opposites and similarities, much like the music inside.

Davis, irrefutably one of the 20th century’s coolest and most important musicians, faced criticism as he approached a louder, more contentious style, but this album’s immense impact on jazz, funk and further on, hip-hop, has solidified its place in music history. Some saw this album as an abandonment of his jazz roots, embracing “white rock” for commercial benefit. Some opposed this view, considering the work a progression, as Davis responded to the shifting political climate with bursts of electric guitar and piano. Klarwein reflected Davis’s futurism by mirroring the social, political and musical discourse of the time. It was a perfect visual synthesis of Miles’s magical amalgam of funk, rock, jazz, and psychedelia, catalysing experimentation in both genres in the Seventies.

Klarwein’s curious beginnings serve as an explanation for the rest of his life. Born in Germany, Klarwein fled with his Jewish architect father and German opera singer mother to Palestine after the rise of the Nazis. He was two years old. One of his more polarising statements, “I am only half German, only half Jewish, with an Arab soul and an African heart”, describes his more bohemian approach to heritage; forgoing labels and convention wholeheartedly.

Klarwein became a famous artist quite outside the art-world path. His lavishly detailed, cosmic eros rendered in bright colours and touched by gold fronted albums by Earth, Wind and Fire and Beck amongst others. A pioneer of the psychedelic visual revolution, Klarwein’s wild, wanton imagery of erotic power encapsulated the free-flowing sexuality of the era.

Beyond the album sleeve, Klarwein’s explorations within the more traditional habitat of the canvas have roused significant interest in recent years. His celebration as artist, not illustrator, comes late – but is in line with current debate as to what art is worthy, and what isn’t. Dylan Jones, who wrote about Klarwein last December in GQ, reasons: “50 years ago there was appalling snobbery towards artists working in the commercial world, but that began to change in the Fifties and Sixties.” The Pop Art movement embraced the commercial world with gusto.

Interestingly, album sleeves have had a resurgence – despite the digitisation of music. This vinyl boom has fuelled a renaissance in cover design and an exciting resurgence in large format music packaging. Oneohtrix Point Never’s 2018 album Age Of is a good example of a return to highly considered artistic compositions. It showcases Jim Shaw’s 2017 work “The Great Whatsit”, which features three women gazing upwards in awe, with plastic advertising grins illuminated by the blue glow of an Apple laptop left ajar. Further intrigue is added with the words “Ecco, Harvest, Excess and Bondage” printed on the protective outer sleeve in an abstract geometric typeface by the album art’s designer David Rudnick; coming together to create a fascinating Retrofuturist cover design.

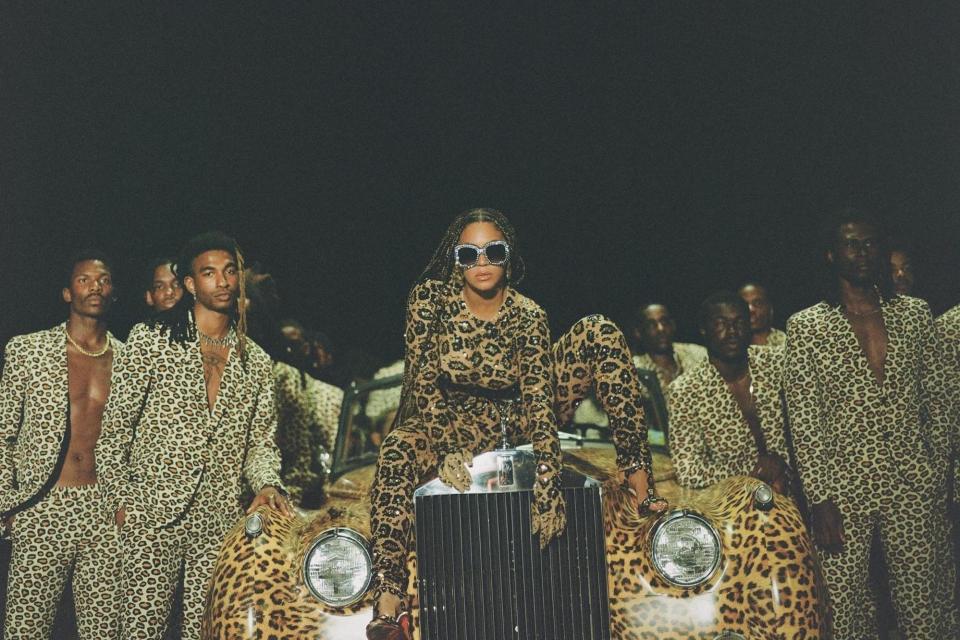

Taking it one step further, the rise of the visual album has transformed music into filmic experience with a full team of collaborators. This year, Beyoncé’s Black is King – an 85-minute visual album that debuted on Disney+ – was intended as a reinterpretation of the story of The Lion King (Beyoncé lent her voice to the character of Nala for the 2019 live-action remake). The film also served as a vanguard for black art and creativity, and is among the most ambitious visual albums made in recent times; in length, scale and ambition. Had Klarwein been around, he may have dabbled in this medium too. Creatives such as Klarwein, who have dallied with many different artistic mediums, have paved the way for this intermingling of mediums; art is so much more interesting when it resists classifications and challenges our beliefs.

Perhaps surprisingly, Klarwein had rather traditional artistic beginnings; in 1948 the teenage Mati and his mother moved to Paris where he enrolled at the Academie Julian. After studying with artist Fernand Leger, he was then introduced to Salvador Dali, Bunuel, and the other protagonists of the Surrealist movement. Klarwein has made reference to bizarre encounters with Dali’s sexual behaviours. Klarwein also learnt much from the Viennese realist painter Ernsts Fuchs; who is said to have imparted the technique of van Eyck and the 15th century Flemish School to him in just one week.

Klarwein’s attachment to Surrealism followed him to New York, where he moved in 1965. Associated with the psychedelic movement at the time, Klarwein attested it was his extensive travels, love of world music and fascination with non-western deities that drove him creatively, rather than the use of psychedelic drugs. He did have a penchant for Fernet-Branca however, but we all have our vices. The assumption that he dabbled in drugs could be justified, given the swirling colours that vibrate with mania prevalent in his art. Balthazar, Klarwein’s eldest son, spoke to GQ about guarding his legacy and insisted it was music that fired his father’s imagination. “He would listen to it constantly,” Balthazar says, “in the studio, the kitchen, in his car. Music was very much part of the family environment. It was African music, Spanish flamenco, classical, Afrobeat, jazz, sometimes maybe some rap or hip-hop or drum and bass. People would send him cassettes from all over the world and he would play them religiously. In his studio up in the mountains there is a small music library, almost an entire record store. His big love was Afro-Cuban music and I guess it’s that fusing of different cultures that made him so particular.”

However, his work could invite contemporary readings of appropriation rather than Afro-Centrism. One painting, Artist and Model (1959) typifies the canon of passive female nude, charged further by her blackness. The painting isn’t very good anyway; but suffers further from an ignorance to the passive sexualisation of a black woman at white male hands. African Americans had been rallying against racial discrimination for centuries, but during the 1950s, the revolt against racism and segregation entered the mainstream of American life. Just four years before Klarwein painted a black woman’s passive beauty – her agency removed by there being no connection to her gaze, Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give her seat on a bus to a white person.

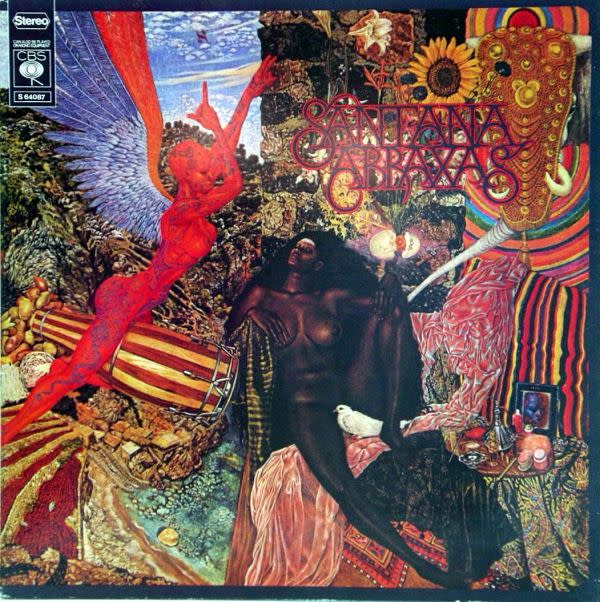

Klarwein painted some of the most important characters of the time, such as John F Kennedy and Jimi Hendrix – a collaborator and friend. But, three landmark pieces of his practice proved his prowess as he tackled more difficult themes such as religion and race on a large scale. Aleph Sanctuary is a cubic temple of all religions featuring 68 paintings by Klarwein and depicting Biblical passages. It took over two years to make a scandal and sensation. Annunciation (1961) was later used by Santana for the cover of his highly successful album, Abraxas. Crucifixion (1963-65), meanwhile features a decidedly sexualised tree of life that shook both puritanical white bourgeoisie as well as radical black advocates – mostly due to the crucified, upside-down black woman with breasts sprouting and tree of life populated by gods, holy men, women and... a harem of nymphs with great knowledge of the Kama Sutra. At his 1964 New York show, one audience member was so incensed that he took to Klarwein with an axe.

Blasphemous? Maybe. “If it's blasphemous it has to be good,” Jones commented. I have to agree.

Klarwein’s Improved Paintings saw him trawling through flea-market canvases and embellishing them with the flourishes of the original creative. This didn’t convince the art world, but supplemented his income and amused him somewhat. Surrealist, Afro-Futurist, Symbolist, Outsider artist… Klerwein resisted categorisation yet history is determined to put him into a box. Truth suffers from too much analysis. He challenged the art world, music and religion and left the world a more interesting place than he found it.

Read more

‘There is a lot of hard work to be done’: How the art world can step up for Black Lives Matter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News