Voices: We need to remember that refugees and migrants are people first

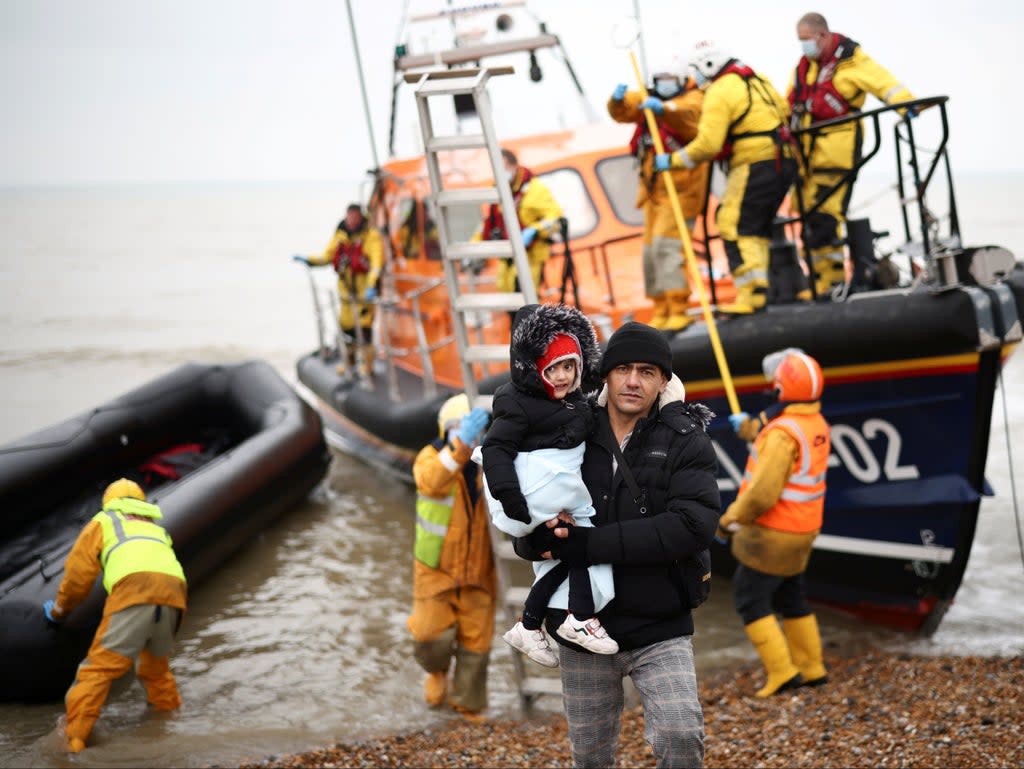

At the time of writing, it is believed that 27 people drowned on Wednesday, while attempting to find safe harbour in the UK. The International Maritime Organisation has described the tragedy as the biggest single loss of life in the Channel since 2014, when it began keeping records – not least because among the number were seven women, some of them pregnant, and three children. The most upsetting and angering thing about this devastating loss of life? It was entirely avoidable.

If the UK provided safe routes into Britain for those fleeing conflict, torture and certain death, then no one would have to cross the Channel in this way. It might be a bitter pill to swallow, but our government’s commitment to the “hostile environment” policy is more to blame than people smugglers in France.

In response to the tragedy, Channel 4 News presenter Krishnan Guru-Murthy tweeted that the 27 people who died are: “Not migrants. People. That’s all.” Guru-Murthy is right.

They were more than “migrants” and more than “refugees”. They were people, with individual identities, hopes, dreams and futures ahead of them. However, it’s also important that we don’t strip away any part of their experience. These people were crossing the Channel in an inflatable dinghy because circumstances demanded it; because it was their best hope of protecting themselves and their children.

The problem isn’t with the word “migrant” or the word “refugee” in of themselves. The problem is what too many of us think those words mean, fuelled by the right-wing press that has long-delighted in setting a xenophobic, racist, anti-refugee agenda.

I firmly believe that this is a conscious strategy, intended to prevent the public from identifying those who are the real threats: the wealthy, privileged elites who seek to destroy our NHS, who roll out crushing (and fatal) austerity measures and who vote against feeding “our own” hungry kids.

No one gets into a flimsy plastic inflatable with their children and puts their life into the hands of strangers because it’s a good laugh, or because they’re keen to nick a job off a random British person. No one attempts this dangerous crossing lightly.

They do so because they are desperate, terrified, stripped of their possessions, their homes and their dignity. If we put just an ounce more thought into what these people have suffered, what they have endured and overcome to make it on to one of these inadequate dinghies – often without even the basic protection of a life jacket – then perhaps the peddled narrative of migrant “cockroaches” and opportunistic, resource-draining foreigners would begin to sound hollow.

The best way to combat the hate and fear that it seems to me that politicians like our home secretary, Priti Patel, greedily feed on, is through greater education and understanding of what brings people to the shores of Britain, shivering and terrified, with only the clothes on their backs.

Let’s dispense with the simplistic “us and them” mentality, one that allows racism and prejudice to flourish, and instead see international politics and the migration of people in a more joined-up way. We must recognise that the destabilisation of countries and the rise of violent regimes is closely linked to the actions and politically-motivated decisions of leaders in western nations.

At least 27 people have died – people who became refugees and migrants because of terrible circumstances in their home countries. People who have experienced unimaginable trauma. Their personhood should never, ever be denied.

And neither should the events that led to their final moments in the freezing water, fighting for breath.

Read More

Editorial: The UK and the west need to help Afghanistan now more than ever

Brexit loyalties will play a key role in the next general election | John Rentoul

What the new coalition in Germany means for the country’s future | Mary Dejevsky

Yahoo News

Yahoo News