Vote-hungry politicians are bewitched by the spendthrift’s siren song

Do you recall when budget deficits mattered, when austerity was all the rage, and when financial markets punished the foolish lapses of spendthrift governments?

In this general election campaign, it appears that the fiscal constraints of old have disappeared in competing puffs of largesse. Our politicians are falling over each other in their attempts to ramp up their fiscal commitments.

The Tories have seemingly rejected the old rules designed to guard against the politically-inspired splurge. Labour appear to believe that, for any spending increase promised by the Tories, the amount should be doubled. The Lib Dems, meanwhile, are happy to pretend they were never part of a coalition government that was known for delivering austerity more than anything else.

What on earth has changed? And will our politicians’ newfound generosity come back to haunt them?

Brexit, inevitably, plays a part. Whisper it quietly, but most politicians — whether Leave or Remain — fear our departure from the EU will ultimately be damaging for economic growth. They also worry that, at least in the short term, a second referendum would merely prolong our national agony.

In other words, the torture of Brexit has made us worse off than we might otherwise have been: investment is lower, productivity is weaker and sterling is softer. A bit of fiscal stimulus might seem like a good idea, particularly when the Bank of England’s monetary firepower is somewhat lacking.

Another reason is that financial markets are — at least for now — remarkably forgiving. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, we have seen a collapse in borrowing costs. Today, the British Government can borrow for 10 years at a ludicrously low 0.7 per cent.

Moreover, we know from US experience under President Trump, and from Japanese experience over decades, that in this kind of environment government debt can rise a long way without any risk of financial collapse. The bond vigilantes — hunter-killers who once roamed the great savannahs of international finance — are no more.

However, while rising government debt may no longer lead to financial chaos, that doesn’t mean governments should indulge in limitless borrowing.

Despite borrowing heavily since the Nineties, the Japanese government has been unable to prevent its economy from enduring three “lost decades”, with lower growth and a decline in Japan’s relative standing in the world.

Japan offers scant evidence to suggest that extra government borrowing can transform a moribund economy. So for all the promises currently being made, there are four reasons for scepticism.

First, governments inevitably invest too much political capital in their pet investment projects. By doing so, they are far too slow to spot when they have backed a dud. Whereas markets can sometimes force you to change course, politicians carry on regardless, fearful of the embarrassment associated with getting it wrong. From nuclear energy in the Sixties through to garden bridges in the more recent past, politicians on both sides of the political divide have too often carried on spending other people’s money beyond a sensible level.

Second, public spending has a habit of being “captured” by those who are the immediate beneficiaries of politicians’ generosity. The increase in health spending when Gordon Brown was chancellor made for attractive headlines, but the government had no real idea of how to measure health sector productivity — who knew whether the money was being spent wisely? Many senior doctors, meanwhile, managed to negotiate very attractive new terms.

Third, as Japan’s experience demonstrates (and, as more than one plotline from Yes, Minister suggested), politicians tend to spend money where it matters politically, not where it provides maximum benefit to society.

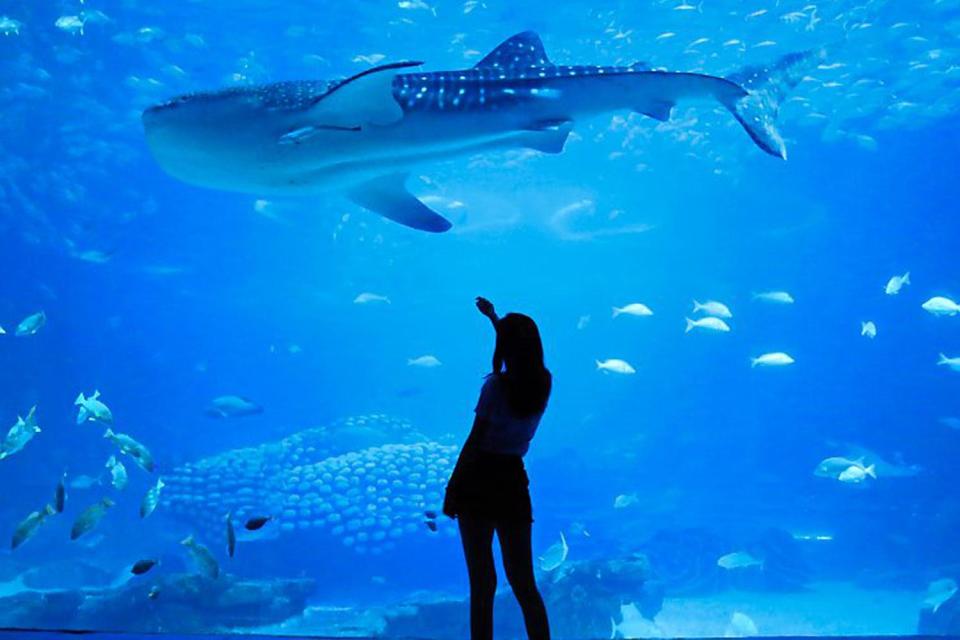

In Japan’s case, there were bridges to nowhere and a publicly funded aquarium, supported by politicians who needed local votes. What begins with good intentions can turn into a form of voter bribery, as nationwide schemes are replaced by acts of local beneficence.

Fourth, unless offset by a rise in household or corporate saving, big increases in a country’s budget deficit will lead to a larger balance of payments current account deficit. Whether that is sustainable depends on the kindness of strangers. It’s possible the rest of the world will look at the UK’s public sector ambitions and be willing to stump up the necessary funds, but it’s more likely that, when we’re struggling to negotiate trade deals post-Brexit, foreign investors will prefer to give the UK a wide berth.

That means either a much weaker sterling, raising import prices and thus crimping people’s wages in real terms or, as is inevitable in Labour’s plans, much higher levels of taxation.

None of this is an argument against public spending in principle. Rather, the claim that the economy can be transformed virtually overnight through much bigger budget deficits and dramatically higher levels of public spending is simply implausible.

There are occasions when sudden changes in fiscal policy can make a big difference, most obviously when there is mass unemployment (there isn’t) or when we’re at war (we’re not). And there are countless examples of where public spending is undoubtedly a force for good. The suggestion, however, that there is at all times an inexhaustible supply of shovel-ready projects that can be brought to life through a bit of extra money does not stand up to scrutiny.

Economies are remarkably complex ecosystems. Politicians often forget this, pandering to the sirens’ vote-gathering songs. That’s why we normally have fiscal rules: they block politicians’ ears with wax and tie our leaders to the mast, saving them from their worst instincts.

And that’s why this general election is highly abnormal: the ears have been unblocked, the mast has been chopped down and the sirens’ songs are deafening. Odysseus would not be impressed.

Stephen King (@KingEconomist) is HSBC’s senior economic adviser and author of Grave New World (Yale)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News