‘Warm, loving, generous – but he had demons’: inside the life of Meat Loaf

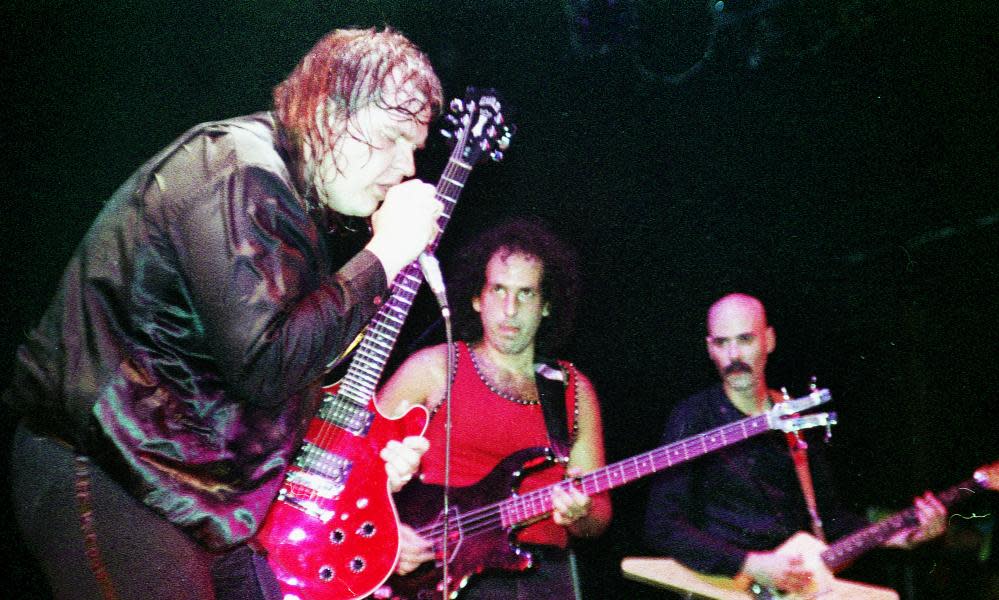

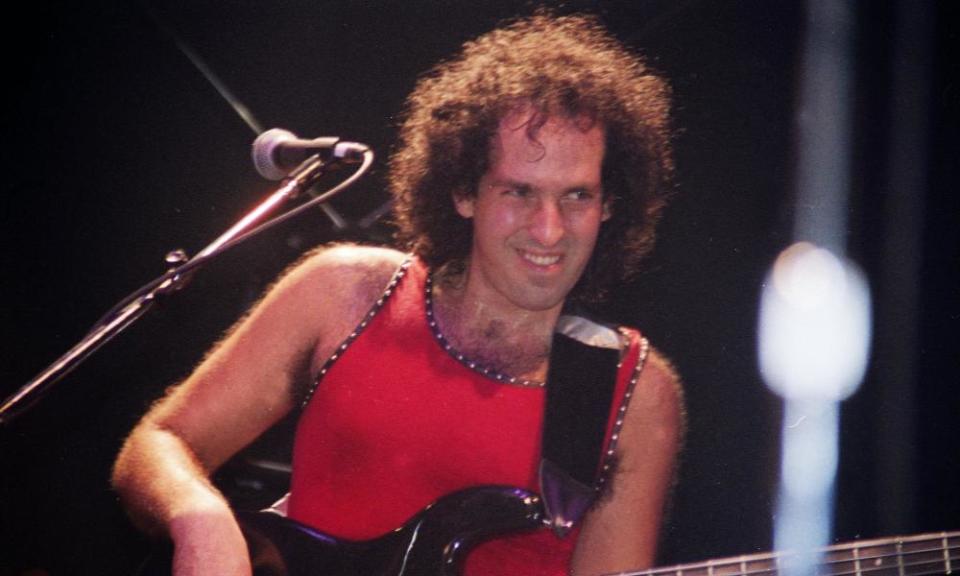

Steve Buslowe played bass for the rock star for 20 years, witnessing his brilliance and his violent moods at first hand. He recalls a musician determined to always evolve

The morning after Meat Loaf died, his former bass player Steve Buslowe was reading through the many celebrity tributes to the bombastic singer when he came across one that made him laugh.

“I saw a comment that Stephen Fry had made about Meat being cuddly and frightening at the same time. I laughed because that’s perfect. He was such a big teddy bear. He was sometimes warm, but then he could also get a little manic, a little out of control, maybe a little violent. So you never knew who he was going to be. He was kind of fearless in being warm and generous, but also in his anger. If he got frustrated with something, he wouldn’t go in a corner and pout. He’d throw a chair. He’d be in your face to let you know how he felt.”

Buslowe, 67, is in a contemplative mood as he speaks via Zoom from his home in Connecticut. The musician and backing vocalist, who is my uncle, played with Meat Loaf for the best part of the singer’s career, witnessing his rise to megastardom during the Bat Out of Hell tour in 1977-78, the wilderness years of dwindling sales in the mid- to late-80s, and his resurgent global success in the early 90s with Bat Out of Hell 2: Back Into Hell.

The singer’s talent and temperament made a strong impression on Buslowe from their first meeting, after the bass player auditioned to join Meat Loaf’s live band, later called the Neverland Express. “When I first met him at the rehearsals, I knew he was a unique person,” he says. “I still remember having chills watching this man sing four or five feet away from me. He had this amazing operatic voice. I knew I was dealing with somebody very special but complicated. As time went on, I saw how complicated he would become.”

Buslowe, who had been playing with funk fusion bands before the tour, admits he didn’t immediately get Meat Loaf’s dramatic sound. “I said to myself: I can’t believe I just joined a band that has a song called Paradise by the Dashboard Light. Though, of course, I grew to love it.”

He was not alone in having this initial reaction. The band was met with a hostile crowd at their first gig in Chicago, opening for the rock group Cheap Trick. “People were swearing at us, throwing things, saying really nasty things about Meat Loaf being overweight,” says Buslowe. “It was horrifying. But I think it got us revved up, no pun intended, to say screw you, we’re going to push it.”

This rocky start to the tour was amplified by Meat Loaf’s erratic behaviour. Buslowe recalls how the singer hired one of his friends to be their driver-cum-tour manager, despite having no relevant experience. On the way to a gig in Youngstown, Ohio, the friend’s fast, nausea-inducing driving led to a punch-up.

“Meat had gone up to the front and said slow down, everybody’s going a little crazy,” says Buslowe. “Well, the guy wouldn’t. Meat went nuts and he goes: ‘Pull over!’ Well they pull over at a rest stop right off of this highway and the two of them get out and start beating the crap out of each other!”

Buslowe remembers looking through the window of the band’s RV at the songwriter Jim Steinman, the creative mastermind behind Bat Out of Hell and Meat Loaf’s other most epic hits, watching bemusedly the fight on the grass in the truck stop. “I’m sitting there going: what did I get myself into? This is madness! Of course, Meat and the guy wound up being friends again. But that was Meat’s personality: he could get really angry with you, and after he gets that out of his system, he can be your best friend.”

Steinman and Meat Loaf’s musical partnership was infamously fractious. Buslowe recalls how the balance of power shifted towards the singer as that first tour gained momentum and his star rose. “There were some people who said, not that I would use this expression, it was like Frankenstein and the monster – where Jim was really the brains behind the songwriting and Meat was just the singer,” he says.

“As the tour developed, Meat got a more dominant role because he got the attention. But he also knew that instead of it just being like a theatrical show, he had to be more aggressive on stage and make it more rock’n’roll. And I think he was proven right.”

However, as detailed in his 1999 autobiography, To Hell and Back, the singer increasingly struggled with the demands of touring. His voice began to give out on him. He started using cocaine. He raged at the band members and audiences, throwing microphone stands at them. Then in May 1978 he fell off the stage at a gig in Ottawa, breaking his leg and leaving him unable to perform. He had a nervous breakdown.

“My memory, a lot of times, was sitting in a hotel lobby waiting for Meat to walk out of the elevator door,” says Buslowe, who did not discuss the singer’s drug and mental health issues. “Depending on the look on his face or the way he walked, I knew what kind of day I was going to have. I really learned to recognise what to say and when to say it, and, more importantly, if he’s in a lousy mood, when not to say anything.

“Meat wasn’t always good with a lot of pressure. I felt sorry for him because he was a little fragile in that way. But without him there was no band. We were really hired musicians. For me, it was a struggle to be waiting on him because you have no control. There was also a lot of frustration coming from the record company and the managers because everybody’s trying to make money.”

Amid the singer’s ongoing crisis, Steinman decided to make his own album, Bad for Good. Although he subsequently wrote Meat Loaf’s 1981 album, Dead Ringer for Love, best known for his hit duet with Cher, neither record performed on a par with Bat Out of Hell, which Buslowe partly attributes to them being released so close together. With this diminishing success, the singer and songwriter’s relationship fell apart.

During this period, Buslowe co-wrote four tracks on Meat Loaf’s third album, Midnight at the Lost and Found, including the title track, which reached a disappointing peak of No 17 in the UK. “It was thrilling for me to perform my own songs,” he says. “Regrettably, the album didn’t get good reviews. I don’t think Meat cared for it all that much.”

The bass player left the band in 1984, returning two years later when Meat Loaf began touring smaller venues, including pubs and clubs, in an attempt to revive his career back and stave off bankruptcy. Paradoxically, Buslowe says the singer’s voice was at its best during this low point of his fame.

“It was fun for me because he was a lot more relaxed,” he adds, attributing much of this to the calming influence of the singer’s first wife, Leslie. “He didn’t have a big record deal. We were just going day by day, building it back up. It was a real healthy time for him, and also for me to watch him grow.”

By 1990, Meat Loaf and Steinman had reconciled, leading, three years later, to the release of Bat Out of Hell 2. The album sold more than 14m copies worldwide, with its lead single, I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That), topping the charts in 28 countries. “When things got successful again, there was more money, but there was more pressure again, and I could feel that from him,” says Buslowe, who by this point had become the musical director of the Neverland Express.

“I was kind of middle management between the band and Meat. I helped translate what he wanted. He liked to think of himself as an actor doing a role as opposed to just somebody singing words. He took it upon himself to do a lot of improvisation. You had to always watch him to make sure that you understood what he was going to do. It was always evolving because he was into the performance and really looking at and responding to the audience, and a lot of musicians can’t do that.”

His time with the band ended in 1997, two years after the release of the seventh studio album, Welcome to the Neighbourhood. “I think the relationship ran its course,” Buslowe says, adding that this coincided with Meat Loaf moving from Connecticut to the west coast to pursue his acting career. “I could sense that there was a change in his direction. I’d been wanting to move away from the music business and I felt I wasn’t going to be rehired. I just didn’t feel it anymore.”

Although I remember him being frustrated with Meat Loaf during this period, Buslowe, who has also worked with Bonnie Tyler, Air Supply, Céline Dion and Barbra Streisand, is now more sanguine about the split.

“I wasn’t necessarily unhappy that it ended but it could have ended better. But I have heard from other people over the last couple of years that he still had good feelings about me. So that made me feel good. I think he always respected me and he knew that I was fairly loyal to him. But neither of us picked up the phone to call the other.

“There was a time when I thought he would take a bullet for me,” he says. “I really think that he had this ability to be very protective of people that he cared for. Then there were times when he just didn’t handle people well. I could feel it happening to me a little toward the end of our relationship. I don’t want to say I didn’t take this personally but I just knew that’s the way he was. He really could be a very loving, warm, generous guy. But he had his demons and his struggles.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News