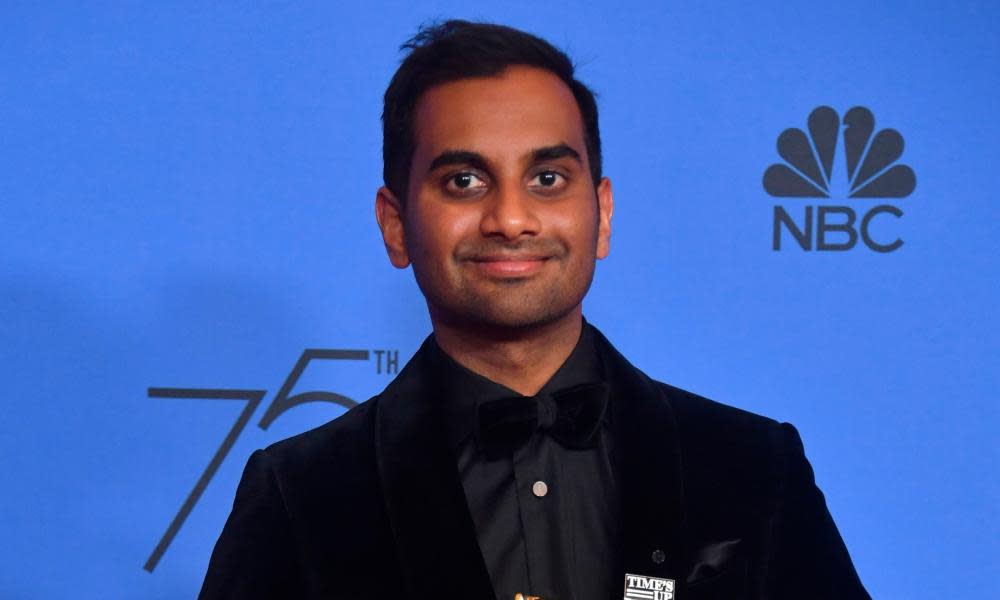

Here’s why Aziz Ansari’s behaviour matters

By now we’ve all become depressingly acclimatised to our favourite celebrities being outed as behaving less than perfectly in their private lives – and this week, it’s an account of an alleged incident involving comic and writer Aziz Ansari that’s gone viral. In a date described as “violating and painful”, a young woman says Ansari repeatedly misread signals, pressuring her into sexual activity she was uncomfortable with.

Published by babe.net, the account makes for deeply unpleasant reading – and not just because of how clearly distressing the victim found the experience. In fact, her distress is even more pertinent and arresting because of how totally mundane it is. (Ansari has responded to the statement, saying “everything did seem OK to me, so when I heard that it was not the case for her, I was surprised and concerned”. He noted that the sex was “by all indications completely consensual”.)

Being coerced into sex you’re not very comfortable with is something that’s happened to almost every woman I know

As a young woman, I can just about count on two hands the number of experiences I’ve had like this – and there are probably even more I’ve forgotten about. Being coerced or pushed into sex you’re not particularly comfortable with is something that’s happened to almost every woman I know, to the extent that many of us just stoically accept that it can be part and parcel of sexual relations.

To some extent, this is true. Ansari’s behaviour was normal – and therein lies its true horror. As Guardian writer Jessica Valenti put it on Twitter , enthusiastic consent “goes against everything we’ve been taught about sex”. Men are encouraged to push our boundaries, taught that women often “play hard to get” and may need “convincing” into sex. We’re seen as gatekeepers – sometimes not particularly into sex, but willing to give in to it given the right circumstances. Our limits are tested time and time again; sometimes a hand slowly moving back to the place we just removed it from, others a whispered “you know you want to”. The number of women sharing this story along with their own similar experiences is telling: how many of us has this happened to? And how many of the men who committed these acts would ever realise that they’ve committed a form of assault?

This isn’t unrelated to the (completely unfounded) argument that the breadth of #MeToo has become problematic, and that to include everyday incidents related to sex and dating, rather sticking to more severe abuses, is to conflate the two.

This assertion implies that women don’t know the difference between rape and coercion – which they do. Nobody is arguing that what Ansari is alleged to have done is equivalent to the more serious crimes Harvey Weinstein has been accused of, or even to the more obvious abuses of power perpetrated by men such as Louis CK. What we are saying, however, is that all of these things exist on a spectrum of abusive behaviour that negatively and persistently impinges upon women’s lives.

What’s especially difficult about this case, however, is that it will force men to examine their own behaviour in a way that most of them have not had to do so far during this moment. Someone committing multiple, serious sexual assaults and rapes is easy to characterise as a predator, a monster, and a thousand miles away from the lives and behaviours of the often well-meaning men who are trying to engage with this cultural moment. Ansari’s alleged behaviour, however, is likely to hit much closer to home.

This may be hard for many men to swallow. But if we truly want to force a cultural change in how we navigate sex and relationships, as I believe that most of the men in my life sincerely do, then we need to understand how abuses of power can manifest in small ways as well as large ones.

This shift is simply not going to happen if we don’t take a serious look at behaviour that we believe to be part of the “normal” range of sexual relations. It’s not enough to merely castigate acts we have long known to be unacceptable – it’s time we took a far wider view.

• Emily Reynolds is a freelance journalist and the author of A Beginner’s Guide to Losing Your Mind

Yahoo News

Yahoo News