Why leaving school and becoming a parent are bad for the waistline

Becoming a parent adds 2.8 lbs (1.3kg) to new mothers but fathers are not affected, new analysis shows.

In fact, gaining weight and becoming less active are an inevitable downside of adulthood that affect most people when they leave school, the University of Cambridge has discovered.

Researchers analysed 19 studies and found that on average activity levels plummet immediately after exiting high school, with men losing 16.4 minutes of moderate-to vigorous exercise each day, and women 6.7 minutes.

It means that in a week, men lose the equivalent of 76 per cent of the recommended activity level of 150 minutes of exercise a week and women 30 per cent.

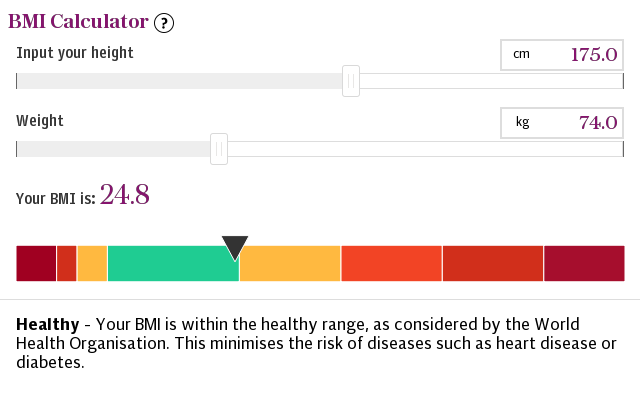

Women had the double burden of gaining weight when having a child, with the Body Mass Index (BMI) of the average mother increasing by 17 per cent in the five years after having giving birth, compared to women without children.

A woman of average height 5ft 3inches (164cm) who had no children gained around 16.5 lbs (7.5kg) over five to six years, while a mother of the same height would gain 19.4 lbs (8.8kg), equating to increases in BMI of 2.8 versus 3.3. There was no similar impact on fathers.

Experts believe the extra pounds were not just the addition of 'baby weight' which might be expected after giving birth, but also the decline in physical activity of mothers, who often become tied to their home with young children.

They found that physical activity decline in parents versus non-parents, but there was no difference in diet.

“BMI increases for women over young adulthood, particularly among those becoming a mother,” said Dr Kirsten Corder, also from Centre for Diet and Activity Research (CEDAR) and the MRC Epidemiology Unit.

“Interventions aimed at increasing parents’ activity levels and improving diet could have benefits all round.

“We need to take a look at the messages given to new parents by health practitioners as previous studies have suggested widespread confusion among new mothers about acceptable pregnancy-related weight gain.”

Many people tend to put on weight as they leave adolescence and move into adulthood, and it is the age when the levels of obesity increase the fastest.

This weight gain is related to changes in diet and physical activity across the life events of early adulthood, including the move from school to further education and employment, starting new relationships and having children.

On average, for men and women, levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity fell by 11.4 minutes per day, or 79.8 minutes per week when they went to university.

“Children have a relatively protected environment, with healthy food and exercise encouraged within schools, but this evidence suggests that the pressures of university, employment and childcare drive changes in behaviour which are likely to be bad for long-term health,” said Dr Eleanor Winpenny from CEDAR and the MRC Epidemiology Unit at Cambridge.

“This is a really important time when people are forming healthy or unhealthy habits that will continue through adult life. If we can pinpoint the factors in our adult lives which are driving unhealthy behaviours, we can then work to change them.”

The research was published in the journal Obesity Reviews.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News