Why a ‘liberal’ pope is playing host to Donald Trump | Catherine Pepinster

When the president of Ireland, Michael D Higgins, visited the Vatican on Monday, he gave Pope Francis a gold and white bell, a symbol of their mutual concern about global warming. It’s usual for heads of state and the pope to exchange gifts during a meeting but it’s hard to imagine Donald Trump, who is due to visit Pope Francis on Wednesday, would ever consider a gift that might have anything to do with climate change. The US president thinks global warming was invented by the Chinese to harm American manufacturing, while the pope is so convinced of its existence he wrote a papal document dedicated to climate change and its consequences for the world’s poorest.

This is just one of the issues on which the pope and the president do not see eye to eye. They are diametrically opposed on what the world should be doing about refugees, migrants and walls. For while Trump has advocated building a wall to keep out migrants crossing into the US from Mexico, and said that the Mexicans should pay for it, Francis said this year that it was a Christian calling to “not raise walls but bridges, to not respond to evil with evil, to overcome evil with good”.

And in improvised remarks at a weekly papal audience in February, it was thought that Francis was referring directly to Trump’s demand that Mexico pay for the wall when the pope said: “A Christian can never say, ‘I’ll make you pay for that.’ Never. That is not a Christian gesture.”

Nor is the pope likely to be impressed by the series of arms deals signed by the president with the Saudis this week. Francis has continually denounced the arms industry, calling manufacturers “merchants of death”, and even told Congress during his visit to the US in 2015 that the arms industry was drenched in blood.

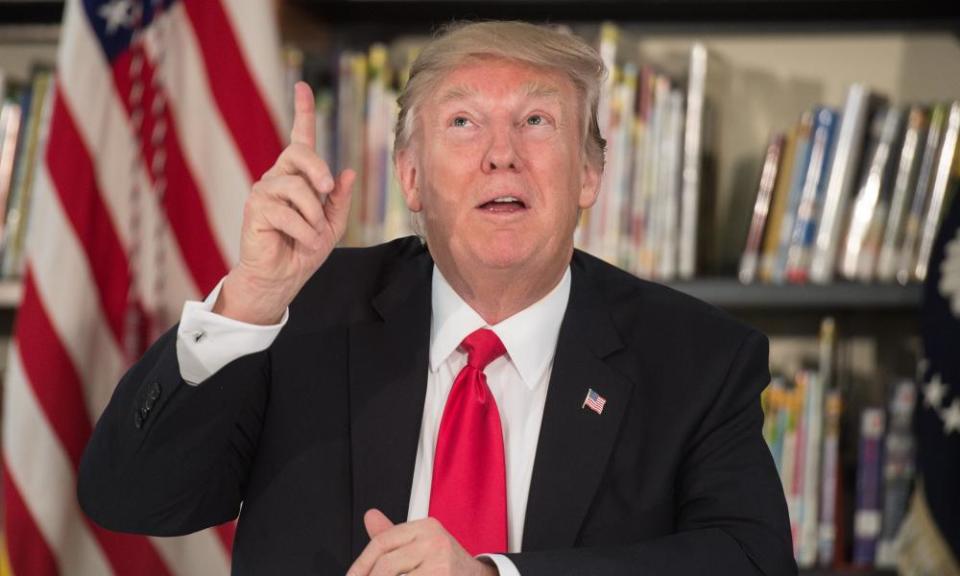

But however awkward the differences in moral outlook, this meeting will nevertheless be an important one for Trump, leader of the world’s temporal power, with the leader of its spiritual superpower. The president’s PR advisers will hope that being seen alongside the charismatic and highly popular Francis will give Trump kudos, and that there will be more to it than the curiosity of seeing this odd couple trying to get along.

That PR opportunity has been taken up countless times by world leaders visiting the Vatican. But there are also pragmatic reasons why it is worth world leaders engaging with the Catholic church. It is the biggest global network of providers of education and healthcare, and with America being the world’s largest donor of humanitarian aid, there will be areas of work where Trump’s team will want to find common ground.

This is where the relationship between the Trump administration and the Francis papacy might see a meeting of minds – and it won’t please liberals who usually find this pope more palatable than his predecessors.

The Roman Catholic church maintains its forceful opposition to abortion, while one of Trump’s most notable policy reversals from the Obama era has been to sign an executive order banning international NGOs from providing abortion services or offering information about abortion if they receive US funding.

Secularists who decry religion may object to the regular visits of world leaders to the Vatican and dislike its particular status, due in part to it being recognised since 1929 as a sovereign entity and being subject to international law.

But they forget what canny politicians – from Ronald Reagan to Tony Blair and Angela Merkel – have spotted: the Catholic church can be a useful ally and opinion former with a reach and influence greater than many nations. Its own network of nuncios – the church’s ambassadors – picking up information throughout Africa, Latin America, the Middle East, China, Japan and elsewhere, keeps the church particularly well-informed.

Gordon Brown once conceded that backdoor diplomacy via the Vatican could help to convey the British point of view on issues such as poverty far better than a direct approach to some developing world nations. A prime example of papal behind-the-scenes influence was the role that Francis played in securing a new rapprochement between the US and Cuba.

The success Francis made of diffusing that situation has made him a beacon of hope on the world stage, not just for Catholics like me but others too, starved of global leadership. From his “who am I to judge” remark about gay people to his solidarity with refugees, including taking Muslim families from Syria back to Rome with him to start a new life, we have saluted his endeavours.

It’s also been refreshing that the church has a leader who is not from the west, and instead has enabled the world, via the Argentinian pope, to hear a different perspective. So, some of us have felt misgivings about the endorsement that this meeting might be perceived as giving Trump. We want the pope to be an alternative voice.

But diplomacy is about dialogue, not necessarily with those with whom you already agree. If the pope can find a way of both being firm about where he remains so sharply divided from Trump, yet also find room for collaboration on, say, helping the persecuted Christians of the Middle East, then he will have pulled off one of the most significant high wire acts of his papacy.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News