Why are so many people dying from opiate overdoses? It’s our broken society | Marc Lewis

The number one killer of Americans under the age of 50 isn’t cancer, or heart attack, or road traffic accidents. It’s opiate overdoses. They have quadrupled since 1999. More than 52,000 Americans died from drug overdoses last year. Even in the UK, where illegal drug use is on the decline, overdose deaths are peaking, having grown by 10% from 2015 to 2016 alone. The “war on drugs” continues – but it’s a war we’re losing.

Most drug-related deaths result from the use of opioids, the molecules that are marketed as painkillers by pharmaceutical companies and heroin by drug lords. Opioids, whatever their strength, bond with receptors all over our bodies. These evolved to protect us from panic, anxiety and pain – a considerate move by the oft-callous forces of evolution. But the gentle impact of natural opioids, produced by our own bodies, resembles a summer breeze compared to the hurricane of physiological disruption caused by drugs designed to mimic their function.

Most street opiates (including heroin) are now laced or replaced with fentanyl – the drug that killed the singer Prince – and its analogues, far more powerful than heroin and so cheap that drug-dealing profits are skyrocketing at about the same rate as overdose deaths. The UK’s National Crime Agency said that traces of fentanyl have been found in 46 people who died this year. Users don’t know what they’re getting and they take too much. Fentanyl is recognised as a primary driver of the overdose epidemic.

Society’s response has been understandably desperate but generally wrongheaded. We start by blaming addicts. Then we blame the pharmaceutical companies for developing and marketing painkillers. We blame doctors, for overprescribing opiates, which pressures them to underprescribe, which drives patients to street drugs – cheaper, home delivery via the internet, and zero quality control. We say we’re going to reignite the war on drugs, recognised by experts as a colossal failure from the 1930s onward. We also continue to view addiction as a chronic brain disease, so the benefits of education, social support, and psychological intervention receive far too little attention. Yes, addiction involves brain change, but ongoing medicalisation does little to beat it.

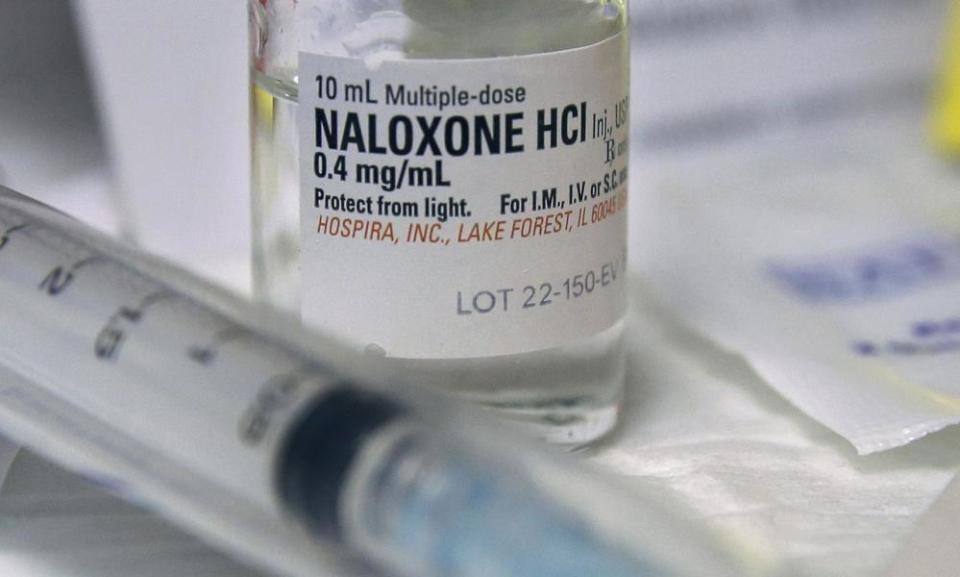

There has been some progress: There are pockets of activity here and there where prescribed opiates – like methadone – are made more easily available to addicts. That’s a good thing, because increasingly desperate addicts are often driven to the street, where they’re most likely die. The availability of Naloxone, which works as an antidote, is slowly wending its way through the drug policy jungle, providing a simple resource to deal with an overdose on the spot. But in most segments of most communities in the US and elsewhere, it is still too difficult to attain.

There are smarter answers at hand – but also smarter questions to be asked. This epidemic compels us to face one of the darkest corners of modern human experience head on, to stop wasting time blaming the players and start looking directly at the source of the problem. What does it feel like to be a youngish human growing up in the early 21st century? Why are we so stressed out that our internal supply of opioids isn’t enough?

Opioids are unique. The opioid system evolved to allow us to function, not panic or shut down, when we are under threat or in pain. That’s why opiates work so well as painkillers. Support from other humans also helps us cope with stress, but that support is underpinned by opioids too. Our attachment to others, whether in friendship, family or romance, requires opioid metabolism so that we can feel the love. Opioids grant us a sense of warmth and safety when we connect with each other.

You get opioids from your own brain stem when you get a hug. Mother’s milk is rich with opioids, which says a lot about the chemical foundation of mother-child attachment. When rats get an extra dose of opioids, they increase their play with each other, even tickle each other. And when rodents are allowed to socialise freely (rather than remain in isolated steel cages) they voluntarily avoid the opiate-laden bottle hanging from the bars of their cage. They’ve already got enough.

In short, mammals need opioids to feel safe and to trust each other. So what does it say about our lifestyle if our natural supply isn’t sufficient and so we risk our lives to get more? It says we are stressed, isolated and untrusting. That’s a problem we need to resolve.

Many have proposed targeted education, community support and interpersonal bonding through group activities. Johann Hari’s powerful book, Chasing the Scream, reviews how such initiatives have worked in diverse societies. An intriguing example is the compassionate, blame-free dialogue that has evolved among high-school students in Portugal, highlighting the dangers of hard drugs and urging the most vulnerable to abstain – not because they’re going to get in trouble, but because addiction is miserable and dangerous. This dialogue has paralleled the decriminalisation of drug use.

Portugal had an astoundingly high heroin addiction rate 16 years ago. It now boasts the second lowest overdose rate on the continent. Social inclusion actually works against addiction while punishment only fuels it.

But the peculiar appeal of opioids tells us more about ourselves as a society, as a culture, than the tumultuous ups and downs of addiction statistics. Today’s young people come of age and carve out their adult lives in an environment of astronomical uncertainty. Corporations that used to pride themselves on generosity to their employees now strive only for profit. Management are as risk-infected as the lowest clerks. Massive layoffs rationalised by the eddies of globalisation make long-term contracts prehistoric relics. I ask the guys who come to the house to deliver packages how they like their jobs. They can’t say. They get up to three six-month contracts in a row and then get laid off so the company won’t have to pay them benefits.

People pour out of universities with all manner of degrees, yet with skills that are rapidly becoming irrelevant. But people without them are even worse off. They find themselves virtually unemployable, because there are so many others in the same pool, and employers will hire whoever comes cheapest. The absurdly low minimum wage figures in the US clearly exacerbate the situation. As hope for steady employment fizzles, so does the opportunity to connect with family, friends and society more broadly, and there is way too much time to kill. Opioids can help reduce the despair.

The opportunity to settle into a viable niche in one’s family and one’s society is being blown away by the winds of unregulated capitalism in a globalised world. As for the intimacy and trust we humans have always sought in each other, in friends, colleagues, and lovers, the bonds are shaky these days. Even if we have the opportunity to connect we’re still too stressed and depressed to get to know each other, to develop trust, to give and receive compassion. Urban life requires juggling high-stress relationships past the point of mental and emotional exhaustion.

The early 21st century offers less structure and stability through religion or family than we humans have experienced in millennia. And maybe that’s just the way it is. But we don’t have to throw away the basic currency of security and interconnectedness entirely. We can build social structures – governments, corporations, community organisations, and systems of education and care – that encourage stability, hope, and trust in our day-to-day lives. Like the school kids in Portugal, we can offer compassion and inclusion as an improvement over heroin. If we fail to do that, we may as well hook ourselves up to an opioid pump. Just to endure.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News