Why a Tory Brexit endangers the rights of workers

As the UK heads to the polls, it is not just deciding on the country’s next government but the future of its relationship with the EU. If the Conservatives, led by Boris Johnson, win the election, the party has made clear it is intent on “getting Brexit done”. This will probably involve pushing through Johnson’s Brexit deal or leaving without a deal.

Both have significant implications for workers’ rights. Promises to preserve the rights enshrined in EU law cannot be taken at face value. The Brexit deal (or no deal) delivered by Johnson’s right-wing Conservative party would probably lead to a rollback of the rights of workers that are enshrined in EU regulations.

The UK has benefited from EU labour protections, which will be vulnerable to the Conservatives’ ideologically driven agenda intent on deregulation. Workers’ rights are a vital issue for voters to be aware of during the general election campaign, and to be educated about more widely to enhance democracy. They affect how people are treated by their employers – whether they can take sick leave, how long they are expected to work each day, holiday pay, and many other rights that we take for granted.

UK workers had few legal rights pre-EU

The UK had few employment laws upon joining the EU in 1973. Nearly all current workplace legal rights derive from the EU via many employment directives that are transposed into national legislation by member states. Unfair dismissal laws and the minimum wage are two of the main exceptions to this, which originated in the UK.

EU directives primarily concern individual employment rights. Although some EU rights are “light touch” in scope, they nonetheless provide EU workers with an extensive minimum floor of protections they would not otherwise have. They encompass issues like working conditions, equal opportunities and discrimination, information and consultation. For instance, the EU Working Time Directive provides a maximum 48-hour working week, paid annual leave of at least four weeks and compulsory rest breaks.

Conservatives have ideologically long opposed and even diluted EU directives granting employment and social rights. The Working Time Directive continues to attract hostility from Tory politicians, even though the John Major government secured a UK “opt-out” from the 48-hour week in the 1990s, if individual workers accept.

Given recent intensifying of longstanding historical Tory Euroscepticism in opposition to what they view as unnecessary interference and regulation from Brussels, it is hard to believe Brexiteers would protect EU rights for workers if still in government after December 12th.

A recent authoritative article on the matter by employment lawyers concludes that, once out of the EU, UK workers’ rights would be exposed to stagnation, divergence and eventual erosion under a Tory Brexit.

‘Room for interpretation’

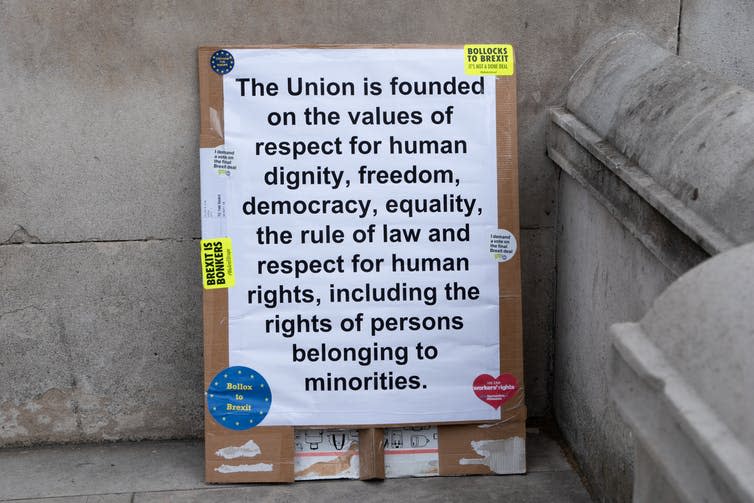

This is given further credence by a Financial Times report that the government has left space to deviate from EU regulatory standards. The FT report mentions a leaked government document stating that the revised Political Declaration – concerning future trade negotiations between the EU and UK – specifically left “room for interpretation” about workers’ rights. The new declaration contains a statement of intent on social and employment standards:

The Parties should in particular […] maintain environmental, social and employment standards at the current high levels provided by the existing common standards.

Crucially, however, this simply amounts to a declaration of intent and is not legally binding. It dilutes “level playing field” commitments on labour standards contained in the May government’s previous deal, which were themselves not legally watertight.

What the present government says publicly and what it may be privately considering seem contradictory. There are concerns in the UK and the EU that the Conservatives want to position the UK as a low-tax, even more lightly regulated economy – moving further away from the European model and closer to the US, with which Britain is seeking a trade deal. Indeed, speaking in New York in September, Boris Johnson outlined such a low-tax deregulatory economic vision.

The EU insists that any future trading relationship with the UK should maintain a level playing field, and it will want to uphold this in any trade deal. But, if the UK is no longer legally prohibited from lowering labour standards below the EU minimum, workers’ rights become largely a matter for domestic law.

There appears little preventing future Conservative governments intent on gradually shredding employment protections to turbocharge neoliberalism. The concern is that a post-Brexit race to the bottom could unfold with pursuit of more extreme labour market flexibility.

This is the preferred direction of travel for right-wing Brexiteers, who have asserted growing power and influence in Johnson’s government. Meawhile, many more moderate “one nation” Conservatives have left the party. It is therefore an understatement to warn that Brexit could be detrimental for workers rights (and employment). And the irony is that this will probably affect leave voting regions the worst.

In comparison, the Labour party promises a big extension in workers’ rights, including strengthening collective bargaining and trade unions. This would be compatible with remaining in the EU and reforming it from within, by lobbying with other left parties for reviving the European social model vision that combines economic growth with decent working conditions. With Brexit still on the horizon, the election result on December 12 has the potential to shape the future of workers’ rights.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Tony Dobbins receives funding from The British Academy and Leverhulme Trust.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News