Why has the UK's wet summer been bad for bees?

This year will be remembered in the UK for its extremely heavy downpours. Intense summer storms resulted in some places exceeding twice their average rainfall. These wet summers make life even harder for bees, who are already struggling with land-use intensification, chemical exposure, exotic species, climate change and habitat destruction.

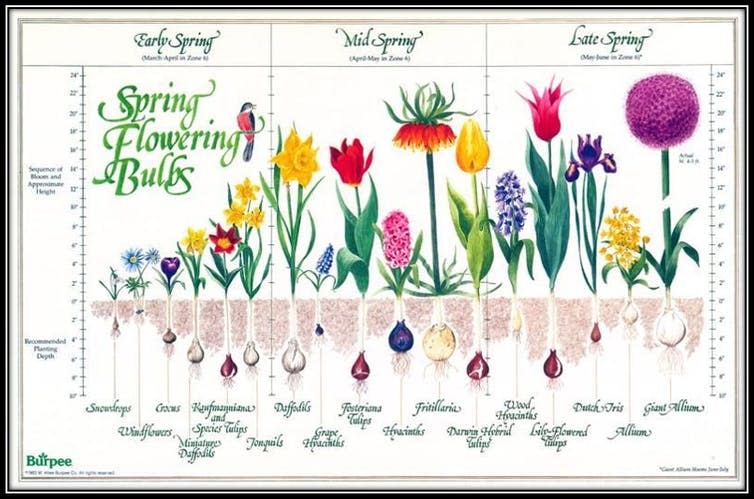

Wild bees (for example bumblebees and solitary bees) have their own yearly schedules to keep to, tightly tied to the trees, hedges and flowers that they feed on. Every year in the northern hemisphere, around February to March, bees that survived the winter begin to emerge with the early spring warm mornings, going out in search for their first meal after a long hibernation.

In a normal year, as summer comes on, worker bees will collect nectar and pollen from flowers to feed to their queen, who in turn lays eggs that produce more worker bees. At the same time, the flowers these bees feed on will become more diverse and more abundant. Native bees have evolved to keep in-sync with this natural system. As more flowers are available, more bees are made within the hive.

However, the continuous growth and expansion of floral resources is abruptly halted by a period of extended summer rains. This causes what scientists are calling the “summer collapse”. Simply put, increasingly wet summers either destroy the flowers that native bees depend on as food or limit the amount of time some bees (like honeybees) spend out in the environment looking for what food is left.

Another problem caused by very wet summers is that smaller bees such as honeybees struggle with flying in the rain, but are better at finding smaller patches of food because of their large number of foragers (around 10,000 per colony). Correspondingly, bumblebees are better at flying in poor conditions, but struggle to find food when there is very little of it because of their comparatively smaller populations (around 25 per colony). Either way, pollinators lose out in bad summers.

This forage collapse happens exactly at a point where their colonies are at their biggest. This means there are more bees than ever, but no food for them to eat. And when bees struggle to get food, they become more susceptible to getting sick.

Some plants will try flowering again later in the season (what is called a “phenological shift”), but by this time, the damage to the bees has already been done. On farmland, bees are sustained by patches of wild flowers and ecological conservation areas planted around the crops such as woodland and hedgerows. Wet summers are just as damaging to wild plants, stripping them of their flowers.

Pollinators on the farm will then not have enough food to sustain themselves before a single mass-flowering event. This is when the acres of cropland that were sowed all at the same time all flower together and need pollination in order to produce food. Bees not being able to survive until this happens means that the farmer’s crop cannot be pollinated enough when it is time.

Read more: Climate change is slowing Atlantic currents that help keep Europe warm

Rainy summers are likely to increase in the future. Wet British summers are closely linked to the El Nino/La Nina cycle and the flow of the Gulf Stream. As global sea and air temperatures rise, the stability of these weather systems has been steadily degraded. This means that these wet summers are likely to increase in regularity, having substantial long term effects on the bees.

Making native pollinators more resilient is a key priority, and there are some things people can do on a small scale that add up to make a big difference. Planting more native flowers in the garden will always make more food available, but as explained above, bees need to feed constantly.

Plants that are resilient to cold wet periods and can flower in adverse conditions like these are particularly important. Ivy, rose bay willow herb, dandelions, heather and lavender are great additions to the garden for this reason. Thinking about resilient plants that overlap when they flower throughout the year can help bees cope in soggy weather.

Having a constant supply of food is also a key priority for the bees, so having plants that come into flower at different points in the summer is helpful: The Royal Horticultural Society have excellent resources for planning out a garden according to overlapping flowering time.

Pollination is a key part of the global ecosystem. Food production is reliant on pollination, and the life cycle of all flowering plants requires pollination. Yet, bees are not the only pollinators. A huge number of hoverflies, small black flies and even bluebottles also contribute to plant pollination. These flies (especially hoverflies like the drone fly) need wet areas and stagnant water to reproduce in. Wet summers obviously result in a lot of puddles and increased rainfall, which these animals need to thrive.

The long-term effect of these changing weather systems raise questions that simply do not have the answers today. Curiously though, more wet summers may bring about a shift in pollinator communities, with a greater ecological reliance on hoverflies and other fly species for pollination. This may mean food production does not suffer, but every time the world loses a species that it relies on for an ecosystem service (like pollination) these systems become ever more fragile and susceptible to further environmental change.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Philip Donkersley receives funding from an ESRC Impact Acceleration Account Grant.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News