Will the GOP turn on Trump? In Watergate, it took 2 years.

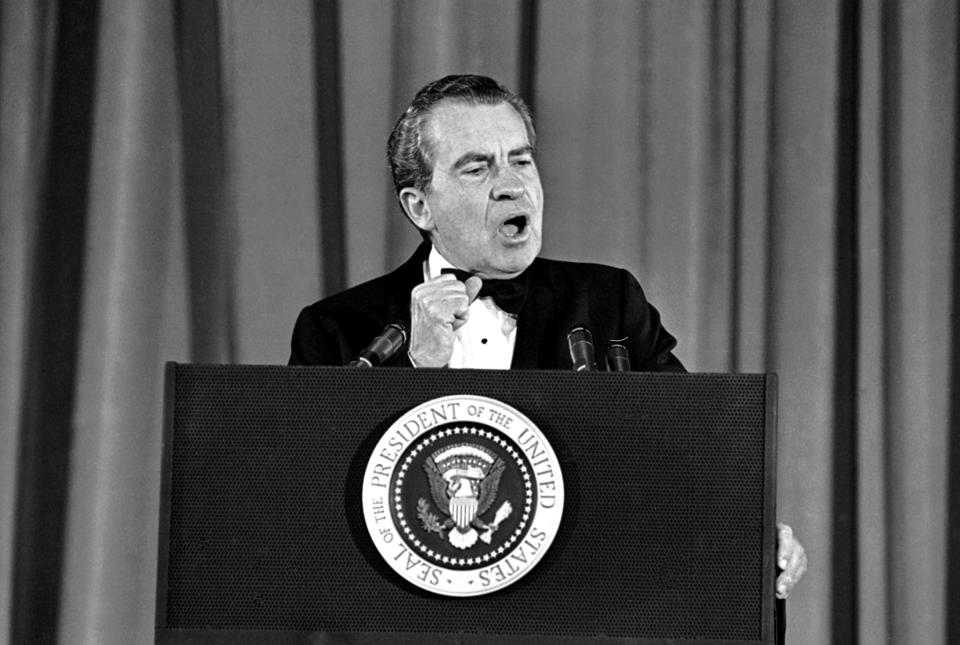

Barry Goldwater had had enough. It was Aug. 6, 1974. The day before, after months of stonewalling, the Nixon White House had released a “smoking gun” tape revealing Richard Nixon had ordered a cover-up in the Watergate burglary. Two miserable years of White House denials had been rendered meaningless. At a luncheon conference with his fellow Republican senators, Goldwater’s anger boiled over. “There are only so many lies you can take,” he said, “and now there has been one too many. Nixon should get his ass out of the White House — today!” The next day, Goldwater traveled to the White House with the Republicans’ House and Senate floor leaders, John Rhodes and Hugh Scott, to deliver a similar message to the president himself. Two days later, Nixon was gone.

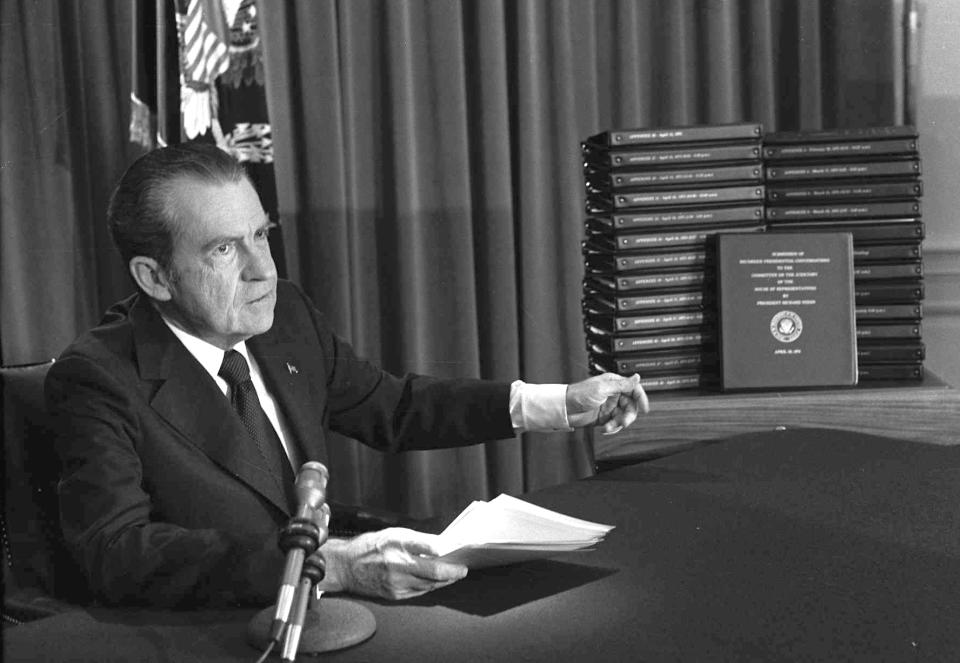

Slideshow: Democracy’s darkest moment: the Watergate conspiracy >>>

In recent days, many who are disturbed by the Trump White House’s descent into Nixonian tactics have recalled Goldwater’s actions with sad longing. So many of the events surrounding the firing of FBI Director James Comey echo Watergate: the meddling with the FBI, the allegations of obstruction of justice, the whispers of a White House taping system and the crisis of credibility surrounding the president. What’s missing, it seems, are the Republicans of conscience. Where is today’s Elliot Richardson, the attorney general who resigned in defiance of Nixon’s order to fire the Watergate Special Prosecutor Archibald Cox? Where is today’s Howard Baker, the Republican senator from Tennessee, who helped lead the Senate’s Watergate hearings with judicious balance and a desire for the truth? Where is today’s Goldwater, a Republican of stature who can stand up and put the country’s interest first?

The stakes are greater than mere historical symmetry. Republicans in the Watergate era, after all, were the minority party in both the House and Senate. As the revelations of Nixon’s misconduct grew, the Democrats used their control of Congress to keep the Watergate inquiry alive through the Senate hearings and through impeachment proceedings in the House. Today, it is the Republicans who control Capitol Hill. A full and fearless inquiry into possible collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia in the 2016 election is unlikely to proceed unless it has the blessing of the GOP. Since the New York Times reported the stunning news that Trump may have pressured Comey to end the FBI’s investigation into Michael Flynn, even some of Trump’s Republican defenders have begun to admit there are grave questions surrounding the president’s conduct. The future of the his presidency could hinge on where his party goes from here. If Republicans fail to find their inner Goldwater, any further Nixonian power grabs from Trump may well go unchecked.

Yet the Watergate of popular memory, a plain morality tale in which the villain Nixon was stopped by a line of white-hatted heroes, ignores the more messy realities of political scandal. It took two years for the truth to come out in Watergate. Along the way, politicians in both parties behaved as politicians tend to act in times of scandal — keeping an eye on the national good, yes, but also tracking public opinion and guarding their own self-interest. The story of the Watergate-era GOP is the story of public figures agonizing over the conflicting loyalties to party and country. And it is the story of a few human beings, blindly fumbling their way through crowds of cowardice and calculation to find a true, historic, courage.

Congressional Republicans began the Watergate saga by hoping it would simply go away. Official Washington greeted news of the botched burglary at the Democratic National headquarters at the Watergate on June 17, 1972, with a yawn. Few in the GOP saw the stuff of real scandal that summer, even after the Washington Post revealed that funds earmarked for Nixon’s Committee for the Re-Election of the President had made its way into the bank account of one of the Watergate burglars. A broad Watergate conspiracy was easy for Republicans to reason away. Nixon was cruising toward easy victory over Democrat George McGovern, one of the weakest general election candidates in modern history. Why would he bother with dirty tricks?

As the fall campaign heated up, the Nixon campaign looked to fellow Republicans to help dispense with the scandal once and for all. In September, the Republican leaders in the House and Senate, Congressman Gerald Ford of Michigan and Sen. Hugh Scott of Pennsylvania emerged from a meeting with Nixon and assured reporters that Watergate was a “nothing” issue. After a Democrat scorched the Nixon White House on the Senate floor a few days later, Scott rose to object. Although the Democrats, he said, might think they had piled up an impressive litany of charges against the White House, “we know what they’ve really piled up.”

Some in the GOP even saw the scandal as a chance to fire up the Republican base. Decades before “fake news,” Republicans proclaimed the real story in Watergate to be the sins of the liberal media. Among the most acid critics of the early scandal coverage was Robert Dole, a 49-year-old Kansas senator serving as chairman of the Republican National Committee. Dole took particular umbrage with the Washington Post’s coverage, a reflection, he said of Post publisher Katharine Graham’s peculiar hatred for Nixon. “The greatest political scandal of this campaign,” Dole said, “is the brazen manner in which, without benefit of clergy, the Washington Post has set up housekeeping with the McGovern campaign.” In October, Wright Patman, the Democratic chair of the House Banking and Currency Committee, failed in an attempt open an inquiry into the Watergate money trail when 14 of the committee’s 15 Republicans joined six Democrats to block him. The next month, Nixon won reelection with 49 out of 50 states. Congressional Republicans fell over each other in proclaiming their allegiance to the Commander-in-Chief.

In private, their enthusiasm quickly cooled. In the early spring of 1973, evidence emerged linking White House aides H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman and White House counsel John W. Dean to the planning of the burglary. Soon, Haldeman and Ehrlichman were out, along with Attorney General Richard Kleindienst, and Dean was cooperating with the Senate’s Watergate committee. Most Republican senators were appalled by the arrogance and deception of the Nixon team. Some let their frustration show. Oregon’s Republican Sen. Robert Packwood called the scandal “the most odious issue since the Teapot Dome” and Charles Percy, a moderate Republican senator from Illinois, demanded the appointment of a special prosecutor. Even Scott, the Republicans’ floor leader, urged the White House to get the facts out so the country could move on.

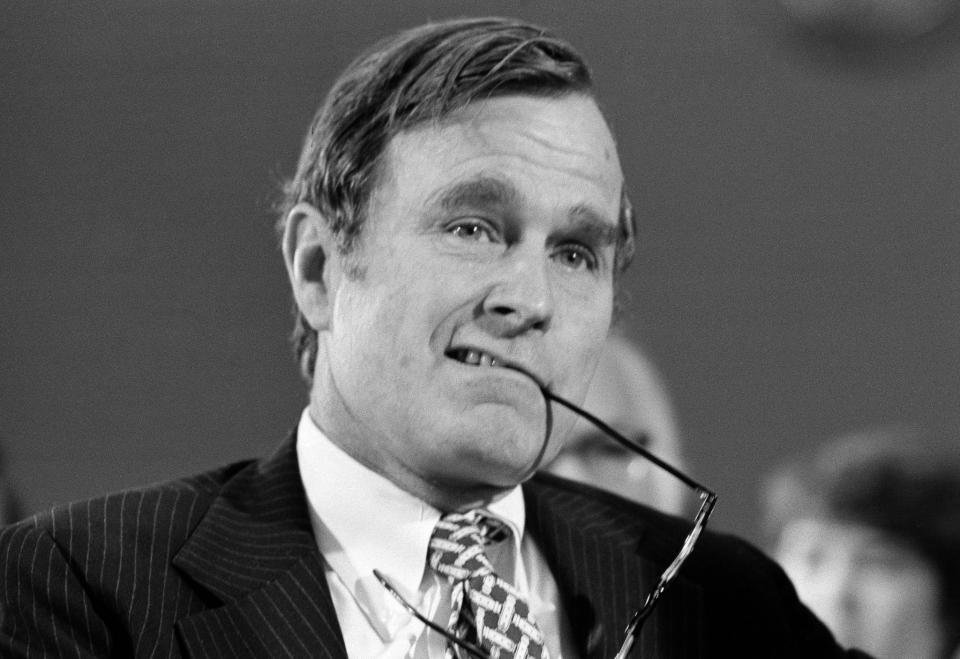

But most in the party were unsure how to proceed, aware that something was rotten in the Nixon White House but not yet convinced that the rot extended all the way to the top. After the election, Nixon replaced Dole at the RNC with an attractive Texan by the name of George H.W. Bush. The future president was startled when he learned of Nixon’s White House taping system in the summer of 1973. He thought about leaving the RNC job where he would have to be a Nixon defender but concluded, his biographer Jon Meacham writes, that duty required him to stay put. “It’s not a time to jump sideways,” he wrote a friend in the fall of 1973, “it’s not a time for me to wring my hands on the sidelines.”

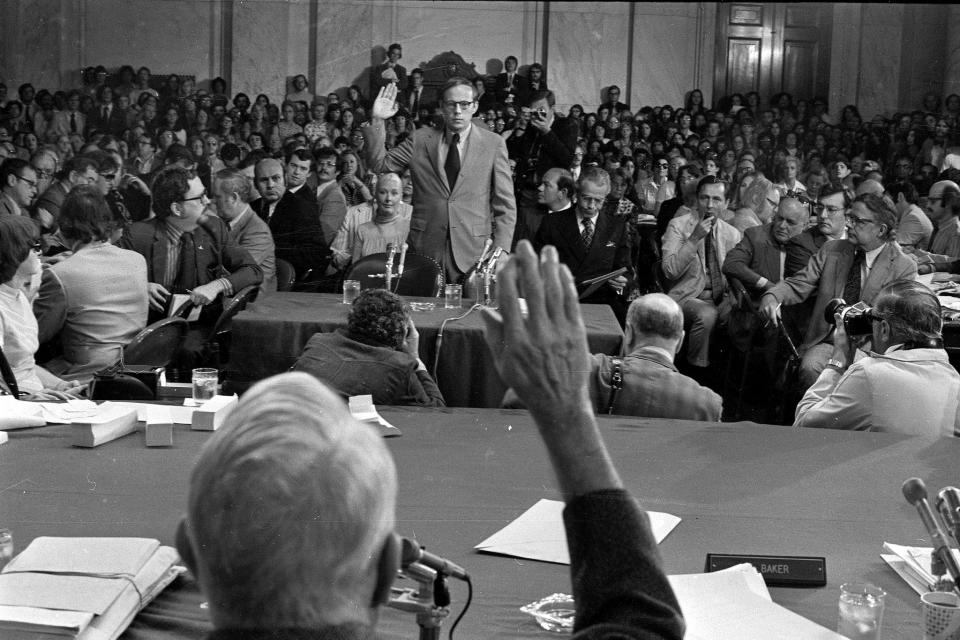

As the scandal raged, Nixon and his circle were cheered that Howard Baker, a courtly Republican senator from Tennessee, would be the vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Campaign Activities — the Watergate committee. Baker, they assumed, would look out for their interests. In January 1973, Baker met with Nixon and said he would do what he could to keep the committee’s witnesses from producing an embarrassing spectacle. Even the lines that would define Baker for history were initially intended to help not hurt Nixon. “What did the president know and when did he know it?” Baker asked in the televised hearing, intending to cast a cloud over Dean’s testimony of a presidential plot. Dean, however, proved a devastatingly effective witness. As the summer wore on, the hearings became a national soap opera and Baker, an honest broker who was committed to following the truth wherever it led, quickly became a phenomenon. “His honesty and quick wit,” wrote one columnist, “not to mention his obvious sex appeal, are capturing the attention of many a housewife programmed to daytime television.” He appeared in the pages of W with the caption “Senator Howard Baker… Watergate Super Star.”

A breaking point for the party came with the Saturday Night Massacre of Oct. 20, 1973, when Nixon’s attorney general Elliot Richardson and his deputy, William Ruckelshaus, resigned rather than follow Nixon’s order to fire Cox (eventually, the No. 3 man at the Justice Department, Solicitor General Robert Bork, carried out the order). Beyond the constitutional crisis, the massacre was a visible rupture within the GOP. Though history remembers his public service, Richardson proudly thought of himself as a politician and one with a bright future in the national GOP. In defying Nixon, the man who had elevated his national profile by granting him three cabinet appointments, Richardson had far more to lose than Rod Rosenstein, the government-lawyer-turned-deputy Attorney General who aided the president’s plot to oust Comey. Still, Richardson concluded that he had no choice but to defy Nixon’s will.

The massacre shocked the nation and an array of congressmen — including several Republicans — suggested Nixon could be impeached for his acts. On “Meet the Press,” Percy flatly declared that Nixon could restore confidence only with “total and complete disclosure” of “everything relating to the possibility of criminal activity.” Yet even as Nixon’s popularity plunged, most Republicans resisted a complete break. “I don’t know what other choice the president had,” Dole said the day after the massacre. “It’s a question of who’s the president, Nixon or Cox.” By then, a pattern for Watergate crises had emerged. Nixon would abuse his power. His fellow Republicans would express grave concern in public and request that the administration take fast steps to remedy the situation. Nixon’s White House staff, more inclined than Trump’s to appear sensitive to critics’ concerns, would pledge greater transparency and cooperation going forward. Then they would continue to stonewall and all sides would settle for the stalemate until the next crisis arose.

An unspoken reason for many Republicans’ intransigence: fear of the GOP base. By then, Watergate had bled into the raging current of cultural resentment that was reshaping the party. Since Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign, the GOP had spoken to the alienation white voters in the South felt over racial integration and the illicit agendas of the Eastern media and the radical Left. For many Republican voters, the furor over Watergate was another symptom of the problem. In early 1974, the New York Times reported on calls to an Alabama congressman’s office: “A local leader of the anti-black Citizens Council [a white supremacist organization] called to complain that Watergate had been invented by the media. A woman called to say that the news media ‘is just looking for bad things to say about our President.’” There was no Fox News then to validate these voters, no Breitbart to counter any juicy new Watergate reporting with a set of alternative facts. But Nixon’s true believers could connect their own dots. The liberal media was telling them they had to be outraged by Nixon’s behavior, just like it told them they had to accept forced integration, the sexual revolution and unrest in the streets. It felt like an incursion on their freedom and it made them as mad as hell.

Ambitious politicians could see that this resentment had a future in the Republican Party and they shaped their behavior accordingly. In 1972, the year of Nixon’s landslide, two young Mississippians, Trent Lott and Thad Cochran were elected to the House, the second and third Republican congressmen elected in the state since Reconstruction. (Nixon won an astonishing 78 percent of the state’s vote.) Shortly after the Saturday Night Massacre, Lott defended Nixon: “Cox is a known liberal, pro-Kennedy Democrat,” he said. “I do not have high regard for Richardson or Ruckelshaus.” Visiting Mississippi a few weeks later, California Gov. Ronald Reagan, who was scoping out a run for the presidency in 1976, railed against “a concerted effort in Washington to undermine [Nixon] and make it appear he is not fit to govern.” Decent Americans, he said, could not stand “silently by while the mob tries to reverse the mandate the country gave in 1972.”

Even in more moderate locales, the politics of the scandal were muddled and hard to parse. Members of Congress were struck by the chasm separating Washington from the outside world. Inside the Beltway, people lay awake in the early morning, listening for the “thud” of that day’s Post on the doorstep, bringing a fresh batch of revelations. Back home, meanwhile, legislators found the scandal rarely came up on lists of voters’ top concerns. As late as June 1974, the Gallup poll showed a slim majority of Americans who believed the scandal had gotten “too much attention.” Lawrence Hogan, a Republican member of the Judiciary Committee, went incognito as a taxi driver in his district, hoping to get a more accurate sense of a typical voter’s mindset. Watergate rarely came up in the cab. When he raised the topic, his fares usually responded with “I’m sick of hearing about it.”

In this uncertain moment, the smart politics was to say as little as possible, to keep calm and see where the facts would lead. But a few public figures were driven by conscience to make another choice. In March, James L. Buckley, the conservative senator from New York and brother of William F. Buckley, the flamboyant editor of the National Review, announced that he had come to the conclusion that Nixon owed it to the country to voluntarily resign. His speech shocked the capital and prompted negative reactions — telegraphs to his office, Buckley reported, were negative by a factor of 3 to 1. One Republican New York county chairman was succinct in his response: “Dumb, dumb, dumb.”

By then, though, there was a ticking time bomb on the Nixon presidency in the form of the secret White House tapes. It went off in late July after the Supreme Court ordered the release of the full recordings. Shortly thereafter, the House Judiciary voted to send three articles of impeachment to the Senate. Seven of the committee’s 17 Republicans voted for at least one of the charges, but only one, Hogan, voted for all three. M. Caldwell Butler, a freshman Republican congressman from Virginia, wept after announced his vote for impeachment. “For years, we Republicans have campaigned against corruption and misconduct,” he said. “But Watergate is our shame.” As a Southerner, Butler had a lot to lose. Butler’s own mother warned him that breaking with his party’s president would threaten his career. “You are probably right,” he told her in a letter. “However I feel that my loyalty to the Republican Party does not relieve me of the obligation which I have.”

On August 7, Goldwater, Scott and Rhodes made their fateful visit to Nixon at the White House. In “The Final Days,” their second book about Watergate, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein described the president quizzing his fellow Republicans about his chances in the Senate:

“How many would you say would be with me — a half dozen?”…

“More than that,” Goldwater said, “maybe 16 to 18.”

“Hugh,” the President said, turning to his right, “do you agree with that?”

“I’d say maybe 15,” Scott said. “But it’s grim,” he added, “and they’re not very firm.”

“Damn grim,” the President shot back.

Nixon, himself a veteran of the Hill, knew that he could not go on.

That fall, with the president gone, his old defenders in the party looked for cover anywhere they could find it. Even in Kansas, an ancient GOP stronghold, Dole faced an alarmingly close fight for reelection in November. He had long since grown disillusioned with the Nixon White House but struggled to explain his reversal on the stump. “It’s an impossible dilemma,” he told the Times. “One guy gives me hell for betraying Nixon, the next comes up to me and says, ‘I’m for you Bob, but you’ve got to get Nixon off your back.” Dole survived in Kansas but elsewhere in 1974, voters doled out harsh punishment to the party that given Nixon safe harbor. Republicans lost 49 seats in the House that year, and four in the Senate, giving the Democrats a majority of 60 votes.

Viewed from a certain angle, the tortured path of the Watergate-era GOP can offer hope for those despairing over the conduct of the Trump-era GOP. By the timetable of Watergate, after all, the Trump-Russia investigations are still in their early days. If there is really more to learn about Trump and Russia, there will be plenty of chances for a courageous Republican crusader to emerge.

But the fact remains that the truth came out in Watergate, in part, because the Congress, under Democratic control, wanted to see it pursued. And sadly, today’s Republicans have even less political incentive than their Watergate predecessors had to do the right thing. In the Nixon years, the party was still learning how to stoke white resentment and paranoia for maximum political gain. Today, those forces are the party’s governing id – just look at the commander-in-chief. A handful of Republicans in Washington were able to follow their consciences in 1973 and 1974, despite opposition from their party’s base. But today, the base has means for displaying its ire in more immediate and intimidating ways than it had in Watergate. A contemporary M. Caldwell Butler would see his tears mocked in endless loop on Fox News. Today, as a prize for hearings conducted with judicious balance, a modern Howard Baker would be greeted with an army of Internet racists, calling him “cuck.”

But shouldn’t Trump’s defenders also worry about their political future? Maybe not. There is little in post-Watergate history to suggest that ambitious young Republicans in today’s Washington — like House Speaker Paul Ryan or Senate Intelligence Committee members Marco Rubio and Tom Cotton — will be hurt for their early-stage indifference to Trump’s conduct. Lott, the young congressman from Mississippi, served on the Judiciary Committee during the impeachment hearings. There, in a move familiar to Devin Nunes and Trey Gowdy, he complained about anti-Nixon leaks. He voted against all three articles of impeachment. He went on to rise through the party’s ranks, eventually replacing Dole as the party’s Republican leader in the Senate. After Nixon’s resignation, the party’s next four nominees for the presidency were all men who had prominently defended Nixon — Ford, Reagan, Bush and Dole.

Meanwhile, Buckley lost his bid for reelection in 1976. Richardson, who in the immediate aftermath of Watergate was one of the most popular public figures in the country, never won elected office again. Among the courageous Republicans, only Baker had a happy future in the party, rising to be Senate leader in the 1980s. When Reagan’s White House was roiled the Iran-Contra scandal, he turned to Baker, with his Watergate-earned reputation for honesty and integrity, to right the ship as his chief of staff.

For those concerned about the fragility of our constitutional order in the Trump era, Watergate offers both consolation and chilling caution. It is history’s best evidence that the system designed by the founders works. When presented with an overreaching executive, the press, the courts and the Congress all did their jobs and the rule of law was preserved. But if it is to work in our present crisis, all of those parties must again rise to the call. That means the Republicans who control Congress will have to step up. Neither political necessity nor short-term pragmatism will be enough to move them. Rather, a few noble Republicans will have to simply listen to their consciences. They will have to come to Goldwater’s conclusion, that there comes a time when you choose patriotism over party. And that there are only so many lies you can take.

_____

Jonathan Darman is the author of Landslide: LBJ and Ronald Reagan at the Dawn of a New America. (Random House, 2014)

Yahoo News

Yahoo News