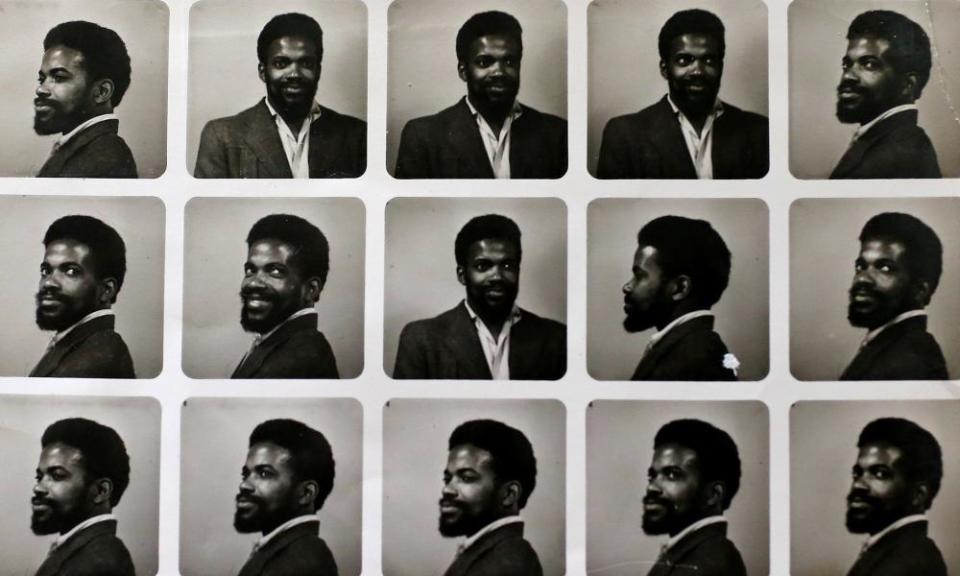

A Windrush passenger 70 years on: 'I have no regrets about anything'

Alford Gardner borrowed money from his father in May 1948 to buy a ticket to travel with his older brother on the Empire Windrush from Jamaica back to the UK, where he had served with the RAF as a ground engineer during the war.

There were more people who wanted to travel than places available. “There was a long queue, lots of people hustling and bustling to get tickets, offering to pay more – but my name was on the list,” said Gardner, now 92.

When the passengers disembarked at Tilbury docks there were RAF officials waiting to welcome former servicemen, but Gardner and his brother, Gladstone, were not interested in returning to the air force and headed straight back to Leeds, where they had done some of their RAF training.

Seventy years later, Gardner is still in Leeds, with his eight children, 16 grandchildren and 21 (he thinks) great-grandchildren all living nearby. He is happy with his decision to move to the UK.

“I have absolutely no regrets about anything. If I could start over, I would do everything the same,” he said in an interview at his home, sitting with two of his daughters, one granddaughter and his newest great-granddaughter, just a few weeks old.

But he acknowledged there had been difficult moments over the decades, as attitudes towards immigration shifted. News of the Windrush scandal over the past few weeks has been particularly disturbing. Although he knows none of those affected, Gardner said he was shocked to hear of Caribbean-born long-term UK residents being deported, detained, sacked from their jobs, made homeless and denied benefits or healthcare.

“I was disgusted. I never thought such things would happen. It is a disgrace. To think of the hard work we put in to get things as they are in England today,” he said.

A friend had warned him in the 1980s that he should be sure to get a passport because otherwise he risked being thrown out of the country, so he travelled to London to make an application. “If he hadn’t told me, this might have happened to me. It shouldn’t be happening at all,” Gardner said. “It’s definitely racism. They haven’t been throwing out Poles or any Europeans in that way. It’s not right. We worked so hard.”

More than half of the passengers on the Empire Windrush had left homes in Jamaica. According to the official passenger list – held by the National Archives – 541 people gave their last country of residence as Jamaica, out of a total 1,027 onboard.

Bermuda was the last country of residence of 139 passengers, while Trinidad was listed for 74 people. Sixty-six passengers came from Mexico, but their nationality was recorded as Polish.

A further 44 passengers were from British Guiana (now Guyana) on the northern coast of South America. England was listed as the last country of residence for 119 people – 12% of the total onboard.

Fifteen people came from other parts of the UK: 10 from Scotland, four from Wales and one from Northern Ireland.

Among the passengers were small numbers from countries as far apart as Burma (five people), New Zealand (two), Norway (one) and Uganda (one). A couple of stowaways were also mentioned on the passenger list: a 39-year-old dressmaker from Jamaica and a 30-year-old from Trinidad.

He will be at a service in Westminster Abbey commemorating the Windrush anniversary on Friday morning, and welcomes the opportunity to try to meet other surviving passengers, but he is very critical of the government’s actions over the passport scandal. “I want the government to sort it out. They’re all legal.”

In his memory, the journey on the Empire Windrush was like a holiday. Many of the other passengers from Jamaica, Trinidad and Barbados had also served in the RAF and were old friends. They slept in hammocks and on bunks on a lower deck, and did not much meet the other passengers. The ship stopped for a few days in Bermuda, where he encountered segregation for the first time.

“That was the first time I saw a sign saying ‘no blacks’. In Jamaica nobody bothered, everybody mixed. But when we got to Bermuda we were trying to have a picnic. A man came to tell us you can’t sit there in that park. We told him what to do with himself,” he said.

There were occasional flashes of hostility in the years after he returned to England. During his time training in Leeds with the RAF, he and other Jamaican servicemen had been welcomed, staying in a hostel to which they planned to return in 1948. But when they arrived back, attitudes had changed and they were told there was no room for them.

Initially they had trouble finding somewhere to live. Gardner slept in a chair for a few nights before they found a room in a house that was let only to West Indians. The landlord knew “there was prejudice; he saw that there was some money to be made”.

Finding work was initially hard because the clerk at the local labour exchange was very hostile. “I went to the labour exchange every day. The little old man would look up from his desk and say: sorry son, nothing for you. I heard that time and again. I’m sure he was racist.”

One morning Gardner visited when there was an employer looking for workers. “I told him I was a motor mechanic. He said: can you strip an engine? I said that’s the least of of my worries – putting it back together, that’s the difficult bit.”

Gardner was hired to help rebuild old Sherman tanks before they were sold to Shell in Kuwait. His new employer asked the labour exchange clerk why he hadn’t recommended Gardner or any of his Jamaican friends, all experienced motor mechanics. He got no reply.

There were other memorable moments of discrimination. When Gardner was setting up a Caribbean cricket club, and had paid to hire equipment, the man in the sports hire shop decided not to give it to him. “Everything was arranged; it must have been racism. We didn’t get angry, we put our money together slowly and bought some more gear each week.” The Leeds Caribbean cricket club is still thriving.

Gardner married a woman from Yorkshire in 1951. “I didn’t see eye to eye with her father, he didn’t like me at all, but he adored the grandchildren.”

Everyone experienced some level of difficulty. “My brother was a very good cabinetmaker but he couldn’t get a job as a cabinetmaker here because he wasn’t in the union. He couldn’t get in the union because he didn’t have a job. So he had to get a factory job,” he said. “We didn’t have time to get angry. As long as we got a job, whatever job.”

There were a few pubs in Leeds that did not welcome black customers in the 1950s and 1960s. “We just thought: ignore them, get away from it, find a place where you can enjoy yourself, then you can relax. If you know they don’t want you then why would you want to be there?”

Gardner was always in work, occasionally coming up against obstructions but shrugging them off and pressing on. “I never said a word about it, I didn’t tell the kids about it, they knew there were nasty people around. I thought: treat everyone respectfully and you will be treated respectfully.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News