Fate of 2,300 separated children still unclear despite Trump's executive order

Donald Trump may have signed an executive order to end the separation of families at the southern border, but his administration is not making any special efforts to immediately reunite the 2,300 children who have already been separated from their parents under his “zero tolerance” policy.

The lack of action has created an additional burden for groups that provide legal and social services to immigrants, flooding non-governmental organisations (NGOs) with cases.

Why are children being separated from their families?

In April 2018, the US attorney general, Jeff Sessions, announced a “zero tolerance” policy under which anyone who crossed the border without legal status would be prosecuted by the justice department. This includes some, but not all, asylum seekers. Because children can’t be held in adult detention facilities, they are being separated from their parents.

Immigrant advocacy groups, however, say hundreds of families have been separated since at least July 2017.

More than 200 child welfare groups, including the American Academy of Pediatrics and the United Nations, said they opposed the practice.

What happens to the children?

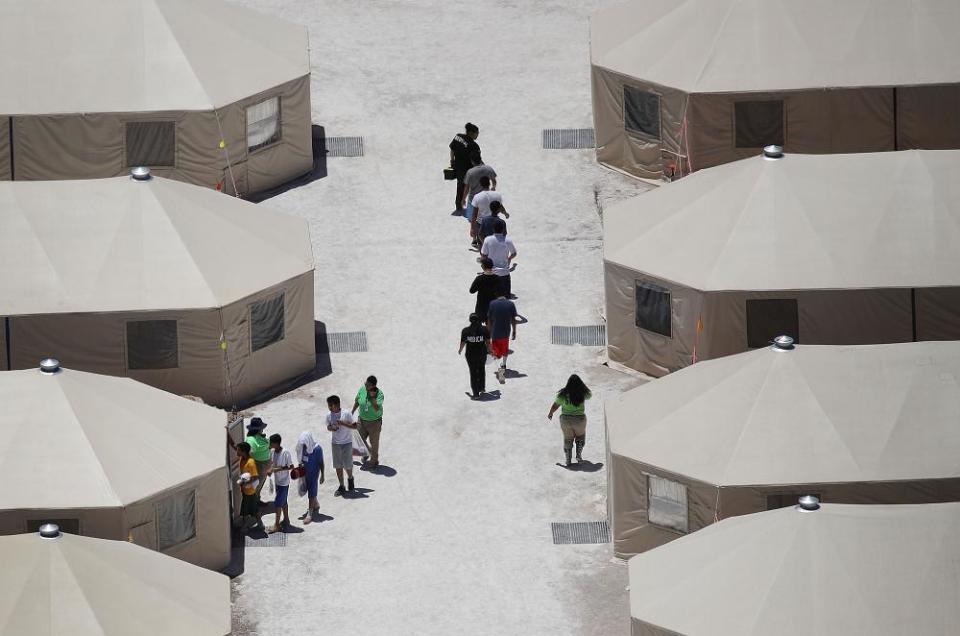

They are supposed to enter the system for processing “unaccompanied alien children”, which exists primarily to serve children who voluntarily arrive at the border on their own. Unaccompanied alien children are placed in health department custody within 72 hours of being apprehended by border agents. They then wait in shelters for weeks or months at a time as the government searches for parents, relatives or family friends to place them with in the US.

This already overstretched system has been thrown into chaos by the new influx of children.

Can these children be reunited with their parents?

Immigration advocacy groups and attorneys have warned that there is not a clear system in place to reunite families. In one case, attorneys in Texas said they had been given a phone number to help parents locate their children, but it ended up being the number for an immigration enforcement tip line.

Advocates for children have said they do not know how to find parents, who are more likely to have important information about why the family is fleeing its home country. And if, for instance, a parent is deported, there is no clear way for them to ensure their child is deported with them.

What happened to families before?

When an influx of families and unaccompanied children fleeing Central America arrived at the border in 2014, Barack Obama’s administration detained families.

This was harshly criticized and a federal court in 2015 stopped the government from holding families for months without explanation. Instead, they were released while they waited for their immigration cases to be heard in court. Not everyone shows up for those court dates, leading the Trump administration to condemn what it calls a “catch and release” program. By Amanda Holpuch

“We would prefer the government to not separate families,” said Megan McKenna, from Kids in Need of Defense (Kind) which offers legal services to unaccompanied children. “But if that has to be the policy then they need to ensure there is a clear protocol that ensures the constant communication between the child and the parent. It’s the only humane thing to do. It’s incredible it’s not happening already.”

Connecting families presents an enormous challenge because once they are detained at the border, children and parents enter two separate systems: for parents, the US Department of Homeland Security and criminal prosecution; meanwhile, children are classified as an “unaccompanied alien child” and transferred to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

“We are dealing with several agencies all trying to coordinate in a disastrous way,” said Zenén Jaimes Pérez from the Texas Civil Rights Project, which provides legal counsel to immigrant families.

Some parents have struggled to find their children, some of whom are being flown to shelters around the country. With no clear process in place, it’s possible some families will never be reunited.

“Permanent separation. It happens,” John Sandweg, who ran the US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (Ice) agency under Obama between 2013 and 2014, told NBC News.

Although both parents and children are allocated A-numbers – “alien” identifiers – and case files, no government body aggregates and tracks them as a family unit. A separated child is treated by the system in exactly the same way as a child who had crossed the border without their parents.

It’s left to the NGOs to put the pieces of the puzzle together.

With each new child Kind deals with, it has to try and figure out their parents’ A-number and search for them on Ice’s online detainee locator system. Some of the organisation’s attorneys have tried to guess alien numbers as they can be sequential if family members were processed at the same time.

Without these numbers – and the children rarely have them – they can also search by someone’s name, age and country of origin, but this relies on the details being entered by border patrol accurately.

“We can also check where the child was apprehended and try to guess where the parent might be detained,” said McKenna.

For parents, there is a hotline for information, but there are long wait times and it can be expensive for family members trying to call from abroad.

The Texas Civil Rights Project is taking a different approach. Every day, attorneys go to the courthouse in McAllen, Texas, to speak with adults waiting to be prosecuted for illegal entry.

They have up to 10 minutes to take down their personal information, including the names and ages of the children they were travelling with and their country of origin.

“A lot of people have fled enormous violence,” said Jaimes Pérez. “We had a mother and an 11-year-old son who fled Guatemala after her husband was brutally murdered. They were then separated by CBP [US Customs and Border Protection].”

The group sees between 30 and 40 people each day. “We don’t expect that to abate any time soon given the administration is hellbent on pursuing the zero tolerance policy,” he said.

‘A wolf in sheep’s clothing’

The executive order that purports to end family separation has not been warmly received by NGOs, particularly the part that seeks to modify a settlement agreement that ensured that children could only be detained for 20 days. The order seeks to be able to detain alien families together indefinitely.

“It’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing,” said McKenna. “It would potentially end separation by allowing the government to keep children in jail-like conditions for even longer. This will continue to ensure suffering of kids and their families in a different way.”

Without an end to the zero tolerance policy of criminal prosecution for every immigrant who crosses the border illegally, parents and children will continue to be separated.

“If parents are still being prosecuted as criminals and put in prisons, they will be separated from their children,” said Jaimes Perèz. Family detention centres are already over capacity, despite plans to build more. “What happens in the meantime?”

A bittersweet side effect to the widespread outrage has been a surge in donations and volunteers, particularly to one organisation, the Refugee and Immigrant Center for Education and Legal Services (Raices), which has raised nearly $15m in just a few days through a Facebook fundraising campaign.

The not-for-profit will use these funds to expand its legal and social services for immigrants. Part of this is the launch of the “Families Together” project that aims, through a coalition of like-minded groups, to centralise data management and help organisations locate and reunite family members.

Raices will also use some of the money for its bond fund to get family members released from detention.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News