Zen and the art of torso maintenance: Matthew McConaughey's guide to life

The biggest question in the universe, writes Matthew McConaughey in his new autobiography (of sorts) is “WHOWHATWHEREWHENHOW?? – and that’s the truth. WHY? is even bigger.” With Greenlights, his love letter to livin, McConaughey attempts to answer these questions and others, such as why he never puts a “g” on the end of “living” – “because life’s a verb”.

Greenlights is not a memoir, though it tells true stories from his life in chronological order. Nor is it “an advice book”. It is “an approach book”, bringing together McConaughey’s insights from 35 years of writing journals, and more of collecting bumper stickers. These “philosophies can be objectively understood, and if you choose, subjectively adopted”. A few are shared here.

‘The value of denial depends on one’s level of commitment’

“Like a good southern boy should”, McConaughey begins with his mother. When McConaughey is eight years old, she enters him into the Little Mr Texas contest. He wins, and his mom hangs a framed picture of him holding his trophy on the kitchen wall. Every morning at breakfast, she gestures to it. “Look at you: winner, Little Mr Texas, 1977.”

Now 50, McConaughey is an Oscar-winning actor, a bankable star and still one of the most handsome men in Hollywood. He has been up and down, endured boom and bust, gone from livin on easy street to trailer parks. He has weathered hard winters of the soul, and long professional droughts. Through it all he’s always been Winner, Little Mr Texas, 1977.

Last year, McConaughey came across the same photo in a scrapbook. The trophy reads “runner-up”. When he confronted his mother, she said the winner was wealthy and won with his fancy suit. “We call that cheatin. No, you’re Little Mr Texas.” McConaughey calls this the lesson of “audacious existentialism”.

‘To lose the power of confrontation is to lose the power of unity’

This proclamation, on a bumper sticker reproduced in the book, captures the young McConaughey’s home life: full of love and also violence. (“I’ve always loved bumper stickers, so much so that I’ve stuck bumper to sticker and made them one word, bumpersticker.”)

McConaughey’s parents divorced twice and married thrice, to each other. His father broke his mother’s finger four times, “to get it out of his face”; he later died from a heart attack mid-intercourse, as he’d always said he would. “Yes,” writes McConaughey, “he called his shot all right.”

At dinner one Wednesday night, his father asks for more potatoes. His mother calls him fat. His father overturns the table. His mother breaks his nose with the phone receiver while calling 911. She pulls out a 12in knife. His father grabs a 14oz ketchup bottle. They circle each other, him slashing her with sauce, dodging her knife.

Their gazes meet, “Mom thumbing the ketchup from her wet eyes, Dad just standing there, letting the blood drip from his nose down his chest … They dropped to their knees, then to the bloody, ketchup-covered linoleum kitchen floor … and made love. A red light turned green. This is how my parents communicated.”

Don’t lose your truck

High school for McConaughey was summer time, all the time. He got straight As and dated the best-looking girl at his school and the other schools. He had a job, no curfew, and a golf handicap of four.

He had two years of acne, brought on by a cosmetic called Oil of Mink that his mother was selling door to door – but, blighted by whiteheads (“blistering geysers of pus”), he was still voted most handsome in his year. “Yeah, I was catching greenlights.”

McConaughey was the fun guy. Not for him, leaning against the wall at the party, smoking and looking cool. He engaged. He took the girls four-wheel driving in his truck, and flirted with them through a megaphone: “Look at the jeans Cathy Cook’s got on today, lookin gooooooood!” “Everyone laughed. Especially Cathy Cook.”

One day he trades in his truck for a sports car that he knew the chicks would dig even more. He gets to school early each day and just leeeaaans against it. “I was so cool. My red sports car was so cool.”

But after a few weeks, he notices a cloud has cast across his summer sky: “The chicks, they weren’t digging me like they used to.” They were out four-wheel driving with someone else. It hits him: “I lost the effort, the hustle, the mudding, and the megaphone. I lost the fun.” He gets his truck back.

It’s never just outside Sydney

Mrs McConaughey suggests McConaughey go on a year-long foreign exchange. His response is immediate: “Sounds adventurous and wild, I’m in.”

His host family in Australia tell him they lived in paradise, near the beach, on the outskirts of Sydney. It turns out to be two hours north and inland – a one-street country town of fewer than 2,000 people.

His host family soon reveal themselves to be intensely strange and, at school, Australian chicks do not dig him. Though the “cultural differences” start to get to him quickly, McConaughey has signed a contract saying he will not leave within a year. And so, for the first time, meaningfully, in his life McConaughey is forced into winter.

In Australia, “Macka” hits nothing but red lights. He starts writing nine-, 12-, 16-page letters home – and then, when no one replies, to himself. Seeking discipline, he becomes a vegetarian, eating iceberg lettuce with ketchup for dinner every night, and practises abstinence.

In Texas, McConaughey had planned on becoming a lawyer. But increasingly he believes it is his calling to become a monk and free Nelson Mandela. By day 148, he is down to 140 pounds, has not only quit school but is on to his sixth job, and actively at war with his host family. His only solaces are the U2 album Rattle and Hum and poetry. “I was in the bathtub every night before sundown jacking off to Lord Byron.”

‘Form good habits and become their slave’

Back in Texas, in college, McConaughey starts to have doubts about his plans to study law. These are cemented when he stumbles upon a self-help book, The Greatest Salesman in the World, at a friend’s house.

The book’s decree to become a “slave” to self-discipline – intended to be read three times a day for 30 days – absorbs McConaughey completely. Soon afterwards he starts film school, where he is a frat guy among goths, an outcast for liking popular movies.

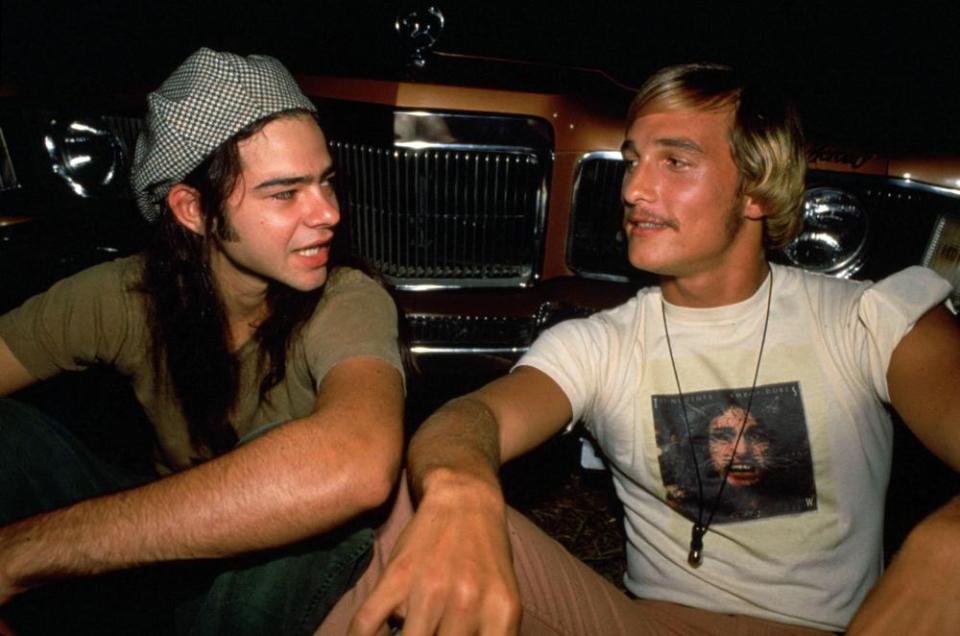

While bartending, he meets casting director Don Phillips, who casts him for a small part in a film called Dazed and Confused. The first words McConaughey ever says on film are: “All right, all right, all right.”

‘When you can, ask yourself if you want to’

McConaughey lands an agent and parts in Angels in America and Boys on the Side. He adopts a puppy – Ms Hud, a lab-chow mix who becomes his longtime companion – and rents a quaint guesthouse on the edge of a national park in Tucson, Arizona. The house comes with a maid, who cooks and cleans.

McConaughey can’t believe his fortunes. “She even presses my jeans!” he raves to a friend, holding up his Levi’s to show her the crisp, starched-white line. His friend smiles, then says something McConaughey would never forget: “That’s great, Matthew, if you want your jeans pressed.”

“I’d never had my jeans pressed before,” he writes. “I’d never had anyone to press my jeans before. I’d never thought to ask myself if I wanted my jeans pressed … Of course I wanted my jeans pressed. Or did I?

“No, actually. I didn’t.”

Follow your dreams

In 1996, A Time to Kill makes McConaughey famous overnight. The press credits him with saving the movies. “Hell, I didn’t know they needed saving, and if they did, I wasn’t sure I was or wanted to be the one to save them.”

Then his mother gives a television crew a guided tour of McConaughey’s childhood home, pointing out “the bed where he lost his virginity to Melissa, I think her name was” – straining their relationship for the next eight years.

McConaughey desperately desires to disappear, to go somewhere he can hear himself think, to check out so that he can check in. Then he has a strange dream. He sees himself naked, on his back, floating down the Amazon river, African tribesmen lined up shoulder to shoulder on the shore. Then he ejaculates. It had “all the elements of a nightmare,” McConaughey marvels, “but it was a wet dream.”

After poring over his atlas for more than two hours, searching for meaning, he learns the Amazon is not in Africa. Undaunted, he packs a backpack with his journal, some ecstasy and his favourite headband and flies to South America – “to chase down my wet dream.”

‘When you’re up to nothin’, no good’s usually next’

In 2000, a few years after his last hit, McConaughey accepts a generous offer to star in The Wedding Planner opposite Jennifer Lopez. He moves – with Ms Hud and his conga drums (“the purest and most instinctual instruments”) – into the legendary Chateau Marmont hotel in Hollywood.

“Single, healthy, honest and eligible”, he revels in the mischief and transience afforded by a high-class hotel. Days of “it’d be rude not to” are followed by mornings of “I don’t knows”. He showers in the daytime, “rarely alone”, and cooks steaks at 3am. He partakes.

Related: Matthew McConaughey: ‘I’ve never done a film that’s lived up to what I imagined’

But after 18 months of hedonism, the booze, the women, the gluttony start to wear thin. McConaughey tires of livin on easy street: “I needed some yellow lights.” He finds himself questioning the existence of a God. “An existential crisis? I’d call it an existential challenge.”

Unrelatedly, he is also losing his hair.

Sometimes it will be the same sign

After shaving his head to encourage thicker regrowth, a two-year course of a product called Regenix applied twice daily and “an aboriginal handshake with a friend that guarantees what two people agree on will happen if they both believe it”, McConaughey’s hairline bounces back better than ever.

Then, shooting Reign of Fire in Ireland, he has a strange dream. He sees himself naked, on his back, floating down the Amazon river, African tribesmen lined up shoulder to shoulder on the shore – then he ejaculates. “Yes, the exact same wet dream I had had five years earlier.”

It was a sign. “It was now time to go to Africa.”

‘Truth’s like a jalapeño. The closer to the root, the hotter it gets’

As Hollywood’s go-to romcom guy, McConaughey is at first unbothered by the fact he is a critical write-off. “I enjoyed making romantic comedies, and their pay checks rented the houses on the beaches I ran shirtless on.”

In July 2005 he meets his future wife, embraces family life, and becomes increasingly unsatisfied by his parts. He tells his agent: no more romcoms. And he waits.

He gets offers of $5m, $8m, $14.5m for two months’ work. He turns them down. For nearly two years, he refuses to give the industry what it wants from him – and one day he is discovered again.

The offers come in droves, almost as many as after A Time to Kill in 1996 – from Linklater, Soderbergh, Scorsese. While shooting The Wolf of Wall Street McConaughey thumps his chest and hums to relax before each take. Leonardo DiCaprio suggests he do it in the scene.

Despite lack of interest from directors and financiers, McConaughey perseveres with making Dallas Buyers Club – and wins an Oscar for it. He is offered the part of Marty Hart in True Detective, holds out for Rustin Cohle, and gets it. “It was my favourite thing on TV. Still is.”

McConaughey is as fulfilled as he’s ever been. He has flipped the script, tipped the scale. They are calling it the McConnaissance. Ever wonder who came up with that? He did. At Sundance in 2013, McConaughey had told one reporter that another reporter had told him, knowing that it would stick. He figured he needed a bumpersticker.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News