How the ZX Spectrum helped bring about famed pop parody Frank Sidebottom

Walk down any British high street in the 1980s, and you’d be bombarded by an array of computers for sale. The Commodore 64, Dragon 32 and Acorn Electron formed a wave of microcomputers, so-called for their small size and cost.

The best remembered of all the “micros” arguably came from Cambridge based company Sinclair Research Ltd. Their ZX81 was a silent, black-and-white machine. Just £70 when launched in 1981, 1.5m were sold, despite their meagre 1KB of default memory. But it was Sinclair’s follow-up computer, the Sinclair ZX Spectrum, that really made a splash. Launched 35 years ago, the company’s first colour micro eventually sold over 5m units worldwide.

The rise of the micros was significant for British business, and the company’s founder, Sir Clive Sinclair, became a poster child for entrepreneurship – although he was eventually forced to sell Sinclair Research to Amstrad’s Alan Sugar in 1986, after a disastrous flirtation with the C5 electric vehicle.

But a different kind of cultural entrepreneur was behind the micro boom, too. The “bedroom coder” of the 8-bit era usually worked alone. Their programs – lines of code recorded onto cassette for playback – would sometimes be self-published and sold through adverts in computer magazines. The more successful coders might gain a lucrative distribution deal with a leading games company such as Bug-Byte, Mastertronic or Virgin, and see their work in shops nationwide.

They were often seen as young geeks, and this was sometimes true. Perhaps the best-known was Matthew Smith, who authored Spectrum’s classic game Manic Miner at just 17 years old. That – and his follow-up, Jet Set Willy – proved how lucrative game-writing could be.

Sitting at their keyboards, bedroom coders had unique, almost auteur-like, visions for their code. Like film directors Alfred Hitchcock or Francois Truffaut, many had full control, with only occasional suggestions from a software distributor. They could earn rock star size royalty cheques, but this was not necessarily about the money. Micros were seen as creative tools, much like a musical instrument.

Listen to the code

The late Chris Sievey knew this better than most. Frontman of new wave band The Freshies, he restlessly experimented with new ideas, including self-produced videos. In 1983, with the band on hiatus, Sievey went solo. His single Camouflage saw his producer Martin Hannett at his most commercial on an expansive, hook-heavy track which used the Cold War as a metaphor for love’s frustrations.

Camouflage’s B-side was even more significant, as it contained three programs written by Sievey on his newly-gifted Sinclair ZX81. Software on vinyl wasn’t a new concept, but the true innovation was the first of the programs: a computerised promo video for Camouflage itself.

Once loaded, the user was asked to press a button on the ZX81 when the first chord of the record kicked in. Thanks to Sievey’s graft, Camouflage’s lyrics were then perfectly synchronised. With the length of each delay loop decided by his trial-and-error, and the ZX81’s frame rolls made into art, Camouflage – though it was a flop on release – remains an inspiration today.

Sievey understood the cultural impact of the micro. He urged his fan club to buy ZX81s, then available for just £40. By the early 1980s, some theorists, such as Alvin Toffler, had already seen a future where computers would turn users into producers. An explicit call to go out and buy a digital creative machine, though, was still fairly rare.

After moving to Sinclair’s Spectrum, Sievey wrote The Biz, a tongue-in-cheek simulation of the music industry, the aim of which is to propel your band to number one in the charts. Originally a board game, its computerised version shared similarities with Kevin Toms’ Football Manager series, one of Sievey’s favourites.

The Biz is redolent of its time. Appearances on kids TV show Saturday Superstore and BBC Radio One’s Peel sessions pave the way to stardom in the game. Sievey’s quirkiness shows in touches like an offer to take drugs: if you do, your song quality increases, but the on-screen text becomes increasingly unreadable.

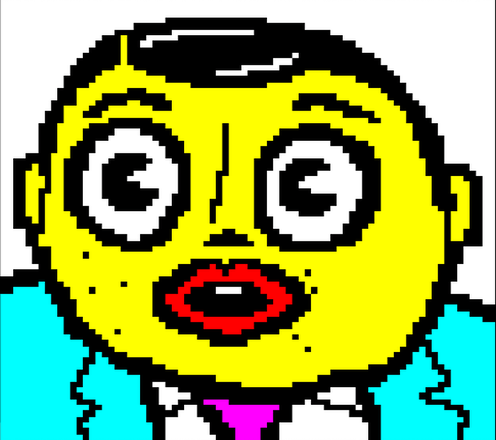

Once again, the game’s B-side is even more interesting than the A-side. It has eight Sievey songs, as well as the debut of his most famous creation, Frank Sidebottom. Frank, the inspiration for a 2014 film, was a papier-mâché headed wannabe pop star, who lived with his mum near Manchester. A cult clownish hero, Frank’s Oh Blimey Big Band conducted reliably shambolic gigs, peppered with covers of Queen and Joy Division songs bashed out on a cheap Casio keyboard.

It’s possible to see Sievey’s retreat into his Frank disguise as a reaction against Camouflage’s failure. But it’s telling that the computer press, particularly the Spectrum magazine Crash, adored Frank. Home microcomputing, and the tools surrounding it, helped bring about one of the best-loved pop parodists of the past 30 years.

The ZX Spectrum was more than a computer: it was, to borrow Frank’s words, absolutely fantastic.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Rhys James Jones does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond the academic appointment above.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News