2 teens won $50,000 for inventing a device that can filter toxic microplastics from water

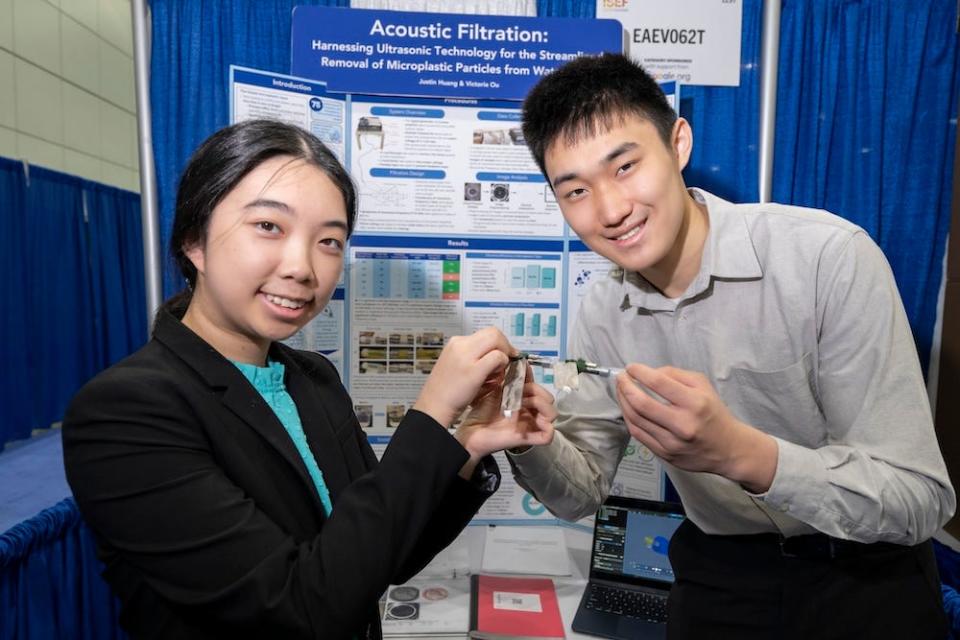

Victoria Ou and Justin Huang, both 17, won $50,000 for their microplastic filtration device.

They tested a new technique using ultrasound to filter microplastics from water.

They hope to scale their device for water treatment plants to reduce microplastic pollution worldwide.

Two teenagers from Woodlands, Texas invented a device that could help address one of the most pervasive and challenging forms of pollution on Earth: microplastics.

These microscopic plastic particles show up in the deepest parts of the ocean, at the top of Mount Everest, and are in everything from the dust in your home to your food and water.

By some estimates, we each inhale and ingest a credit card's worth of plastic per week. Then it can end up in our lungs, blood, breastmilk, and testicles.

Victoria Ou and Justin Huang, both 17, hope to prevent that one day with their award-winning device that removes microplastics from water using ultrasonic — or high-frequency — sound waves.

Ou and Huang presented their work at last week's Regeneron International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) in Los Angeles, where top competitors from science fairs worldwide congregated to share their projects and compete for $9 million in prizes.

The Texas duo received first place in their Google-sponsored category, Earth and Environmental Sciences, and they also snagged the $50,000 prize from the Gordon E. Moore Award for Positive Outcomes for Future Generations.

Though the ultrasonic technique is in its very early stages, the high schoolers hope that one day it could filter the plastic out of your drinking water and from the industrial and wastewater that humans dump into the environment.

"This is the first year we've done this," Huang told Business Insider backstage after receiving their award. "If we could refine this — maybe use more professional equipment, maybe go to a lab instead of testing from our home — we could really improve our device and get it ready for large-scale manufacturing."

While it's unclear how microplastics affect human health, many common chemicals in plastic have been linked to increased risk of cancer, fertility and development issues, and hormone disruption. And we're still a long way from getting rid of microplastics.

The challenge of filtering microplastics

Last fall, while brainstorming ideas for their ISEF project, Ou and Huang visited a water treatment plant. They wanted to find out whether this type of facility already had tools that could remove microplastics from wastewater.

The answer, they discovered, was no. The EPA doesn't regulate microplastics, the employees told Huang and Ou, so they don't remove them from wastewater.

"We knew, from then, to focus on this issue," Huang told BI.

Even if the EPA began regulating these pernicious plastic particles tomorrow, existing removal methods have problems, Huang said.

One solution is to use chemical coagulants, such as aluminum hydroxide, that — when added to water — clump microplastics together into larger, more easily filtered chunks. However, chemical coagulants can also pollute the environment and mess with the PH of purified water. Plus, they're expensive.

There are also some physical filters available, but they clog easily. And biological solutions, like using enzymes to break down plastics, aren't efficient enough to tackle this problem at scale.

"We wanted to find a solution to this because current solutions aren't really effective," Huang said.

So, Ou and Huang — who have been friends since elementary school and connected over their shared interest in the environment — set out to invent their own environmentally friendly, inexpensive, and efficient solution.

How it works

Huang and Ou's device is remarkably small, about the size of a pen. It's essentially a long tube with two stations of electric transducers that use ultrasound to act as a two-step filter.

As water flows through the device, the ultrasound waves generate pressure, which pushes microplastics back while allowing the water to continue flowing forward, Ou explained. What comes out the other end is clean, microplastic-free water.

The two teens tested their device on three common types of microplastics: polyurethane, polystyrene, and polyethylene. In a single pass, their device can remove between 84% and 94% of microplastics in water, according to a press release.

Future work

Ou and Huang believe their technology could be used in wastewater treatment plants, industrial textile plants, sewage treatment plants, and rural water sources. On a smaller scale, it could filter microplastics in laundry machines and even fish tanks.

But first, there's more work to be done. "To reach that stage, I think we need a lot more processing," Ou said. "This is a pretty new approach. We only found one study that was trying to use ultrasound to predict the flow of particles in water, but it didn't completely filter them out yet." The study that inspired the two teens was by New Mexico Tech researchers and published in the peer-reviewed journal Separation and Purification Technology in 2022.

In another 2023 study, researchers at Shinshu University tested a similar ultrasound-filtering method to remove microplastics from water. But Ou and Huang say their device is simpler, more efficient, and the first to use ultrasound to block and filter microplastics directly.

Their technique uses ultrasonic waves to create a pressure wall that blocks microplastics and allows water to flow through, whereas the Shinshu study focused the microplastics into a beam that must then be collected separately, which requires more steps, more infrastructure, and didn't filter as much water.

"I hope we just are able to be able to scale this up, but first we have to refine it because this technology is still at its infancy," Huang said.

Their $50,000 prize could help them get there. In the meantime, though, they're enjoying the moment.

"We were just happy being able to go to ISEF. Originally, we weren't expecting too much, but getting first place and the top award is much more than we ever expected," Ou said.

"This is something that I've been dreaming of my whole life, so I'm still pinching myself trying to figure out if this is real or not," Huang said.

Correction — May 29, 2024: An earlier version of this story misstated the novelty of Ou and Huang's invention. Ou and Huang are not the first to successfully use ultrasound to separate microplastics from water. Previous studies have tested similar methods.

Read the original article on Business Insider

Yahoo News

Yahoo News