The 52 Best Documentaries of the 21st Century

We live in strange times. This young century has been defined by harrowing disasters both natural and man-made, political tribalism, and existential threats to the future of the planet. What better time for documentary filmmaking?

Non-fiction cinema has been evolving since the birth of the medium while capturing a world in motion. From the actualités of the Lumière brothers in the late 19th century to the heavily manipulated ethnographic films of the 1920, from the vérité films of the Maysles brothers to the man-on-the-street agitprop popularized by Michael Moore, documentaries have naturally always been more responsive to their times than any other mode of filmmaking.

More from IndieWire

Not only do they reveal our world to us, but they shape how we view it, and the early years of the 21st century have proven that to be more true than ever before. On one hand, digital technology has infinitely expanded our range of vision, and some of the modern era’s most essential docs have been shot on consumer-grade equipment like iPhones and GoPro cameras. On the other hand, these tools haven’t just granted us new ways of seeing, they’ve also galvanized our desire to look, which in turn has stoked an unprecedented degree of interest in the documentary format on the whole.

Truth has never been so much stranger than fiction than it is today, and the movies show us why. They include personal essays and shocking exposés, touching character studies and sprawling portraits of communal resilience. They feature the cats of Istanbul, the bears of Alaska, and gorillas of the Congo. They document injustices and complex family bonds. Above all, they teach us to see the world around us in new ways. Here are the 52 best documentaries of the 21st century.

With editorial contributions by David Ehrlich, Eric Kohn, Jude Dry, Kate Erbland, Christian Blauvelt, Alison Foreman, and Zack Sharf.

[Editor’s note: This list was first published in July 2017 and has been updated multiple times since.]

52. “Kokomo City” (2023)

To say “Kokomo City” is about the lives of four Black trans sex workers would be true, but it doesn’t give a full picture of its artistry. Making a triumphant directorial debut, filmmaker D. Smith also shot and edited her gorgeous black and white film, adding a host of original songs to her eclectic score as well. Smith employs a lyrical photographic style reminiscent of “Hale County This Morning, This Evening” with a touch of “Shakedown,” but gives her subjects enough space to express themselves that a satisfying character study emerges. In intimate conversations that typically only happen behind closed doors, Liyah, Daniella, Koko, and Dominique share their thoughts on living stealth, what led them to sex work, and the hypocrisy of the men who see them on the down low. It’s as if they’re speaking to a friend (and maybe they are), using a shorthand that forces the viewer to keep up or risk missing the jokes.

Smith often shoots the women from below, placing herself on the floor at their feet, so they hover like queens above the camera. Sometimes, she’ll use a painful anecdote to narrate an erotic photoshoot on a bed, showing the girls luxuriating in their femininity. She interviews a few trans-attracted men, too, and cuts their energetic sermons with footage of a graceful male ballet dancer. The film’s electrifying final shot feels like both a provocation and a celebration; a full-throated embodiment of the bravado and beauty we’ve just been entrusted to witness. May audiences be humble enough to recognize the privilege. —JD

51. “Four Daughters” (2023)

Plenty of films mix documentary storytelling with fiction, but few do it to as wrenching effect as “Four Daughters.” Kaouther Ben Hania’s film profiles Olfa Hamrouni, a Tunisian woman with four daughters, only two of whom are still in her life for reasons that only become apparent in the film at the very end. Hania mixes interviews with Olfa and her two youngest children with scenes where professional actors reenact their lives, documenting the process and the interactions between the professionals and the subject with a patient, still filmmaking style. The result digs into the family’s life together with empathetic curiosity, and its explanation for how the unit unraveled proves heartbreaking. —WC

50. “Mr. Bachmann and His Class” (2021)

Maria Speth proves herself a cinematic heir to Frederick Wiseman with this 217-minute “fly on the wall” depiction of about six months in the classroom of an elementary school for immigrant children in a small German town. 64-year-old Dieter Bachmann is not a perfect teacher, but an exceptionally kind and empathetic one. There are various culture clashes among the children, all hailing from very different backgrounds, and some kinder-crises, but this classroom could practically be a model for a future where our differences are respected and we can all get along together. Watching the film is a kind of Zen experience in hope and tranquility. Not one disconnected from the history of its setting either: Bachmann tells the kids about how their town hosted slave labor during the Third Reich. Through her long takes, Speth creates a deep immersion in the classroom, like you’re part of their conversations too. While it unfolds, you’ll experience something magical: you’ll see the world again as if through the eyes of a child. —CB

49. “13th” (2016)

Ava DuVernay’s documentary “13th” has the precision of a foolproof argument underscored by decades of frustration. The film, which opened the 2016 New York Film Festival, tracks the criminalization of African Americans from the end of the Civil War to the present day, assailing a broken prison system and other examples of institutionalized racial bias with a measured gaze. It combines the rage of Black Lives Matter and the cool intelligence of a focused dissertation.

DuVernay aligns many historical details into an infuriating arrangement of statistics and cogent explanations for the evolution of racial bias in the United States, folding in everything from D.W. Griffith’s “The Birth of a Nation” to the war on drugs. The broad scope is made palatable by the consistency of its focus, and the collective anger it represents.

Visually, the movie offers little more than the standard arrangement of talking heads, archival footage, and animated visual aids, but that’s all it takes to make its incendiary statements resonate across time. The documentary, which followed DuVernay’s feature hits like “Selma” and her early, music-focused documentary works, consolidates some 150 years of American history to show how the country’s current problems with race didn’t happen overnight. It’s required viewing that only grows more essential with each passing day. —EK

48. “All These Sleepless Nights” (2016)

It would be reductive and unfair to say that Michal Marczak’s “All These Sleepless Nights” is the film that Terrence Malick has been trying to make for the last 10 years, but it certainly feels that way while you’re watching it. A mesmeric, free-floating odyssey that wends its way through a hazy year in the molten lives of two Polish twentysomethings, this unclassifiable wonder obscures the divide between fiction and documentary until the distinction is ultimately irrelevant.

Unfolding like a plotless reality show that was shot by Emmanuel Lubezki, this lucid dream of a movie paints an unmoored portrait of a city in the throes of an orgastic reawakening. From the opening images of fireworks exploding over downtown Warsaw, to the stunning final glimpse of Marczak’s main subject — Krzysztof Baginski (playing himself, as everyone does), who looks and moves like a young Baryshnikov — twirling between an endless row of stopped cars during the middle of a massive traffic jam, the film is high on the spirit of liberation. More than just a hypnotically hyper-real distillation of what it means to be young, “All These Sleepless Nights” is a haunted vision of what it means to have been young. —DE

47. “No Home Movie” (2016)

Even before she committed suicide last fall, Chantal Akerman’s final work “No Home Movie” was a tragic statement on the futility of life. An essayistic account of the filmmaker’s relationship to her ailing mother, a Holocaust survivor lost in the fog of faded memories, “No Home Movie” drifts through a somber world with ghostlike intrigue. In between fragments of Skype conversations and living room hangout sessions, Akerman inserts prolonged shots of landscape, sometimes in motion and elsewhere completely still. At one point, she lingers on her murky reflection in a pond. Individually, these moments are difficult to parse; collectively, they amount to an existential wail. At the same time, they carry a profound beauty that hints at more uplifting possibilities.

Of course, “No Home Movie” belongs to a more specific tradition of experimental cinema, both from Akerman’s own oeuvre and many others. But it has a unique rhythm that demands patient viewers and rewards them for their efforts. No matter the depressing undertones, it’s a spectacular parting gift. —EK

46. “Twenty Feet from Stardom” (2013)

Morgan Neville’s Oscar winning documentary “20 Feet From Stardom” hits you like an explosion of joy that’s impossible to shake. What it lacks in narrative innovation it more than makes up for in emotion. Neville spotlights the behind-the-scenes lives of some of the most famous backup singers in music, including Darlene Love, Judith Hill, Merry Clayton, Lisa Fischer and Táta Vega.

Some love supporting other artists and just want to sing, others have dreams to be at the front of the stage. Each woman harbors a self-possessed artistry that is awe-inspiring, and baring witness as they get the spotlight they deserve provides a sensation that makes your heart soar. Try not to stand up and cheer as Mick Jagger listens to Merry Clayton’s stripped vocals on the “Gimme Shelter” chorus. Moments like these are pure bliss for music lovers, and “20 Feet From Stardom” is full of dozens of them. In finding an inspirational topic and telling it with confidence and respect, Neville makes the crowd-pleasing doc of the 21st century. —ZS

45. “Amy” (2015)

Asif Kapadia’s primary skill as a documentarian is his ability to assemble miles upon miles of archival footage into coherent, insightful, and often deeply emotional looks at singular lives. For his much-hyped follow-up to 2010’s exceptional “Senna,” Kapadia turned his eye to one of the modern pop culture’s most exposed — and most misunderstood — stars, using his “Amy” to unpack the tragic rise and fall of singer and songwriter Amy Winehouse.

The British chanteuse’s story had ostensibly been told before, splashed across tabloid pages and gossip blogs, but Kapadia uses his film to find the real person underneath the rumors and lies. What “Amy” does so compellingly is take its audience inside Winehouse’s wild life without judgement or fear, exposing both her flaws and her greatest assets, and showing off her immense talent at every turn. It’s a heartbreaker, because it has to be, because it is, but it’s also a rewarding examination of a life taken too soon, cut too short, and silenced too early. —KE

44. “Kedi” (2016)

The “Citizen Kane” of cat documentaries — take that, “Lil Bub & Friendz” — this sophisticated, artful documentary from Turkish filmmaker Ceyda Torun isolates the profound relationship between man and cat by exploring it across several adorable cases in a city dense with examples. The result is at once hypnotic and charming, a movie with the capacity to elicit both the OMG-level effusiveness of internet memes and existential insights. Torun interviews a variety of locals across Istanbul about their bonds with the creatures, but the cats themselves take center stage, transforming the experience into a spiritual meditation on their significance to modern civilization.

One interviewee argues that the relationship between cats and people is the closest we might get to understanding what it’s like to interact with aliens. If so, “Kedi” goes a long way towards making first contact. Then again, dog people may find themselves in the dark. —EK

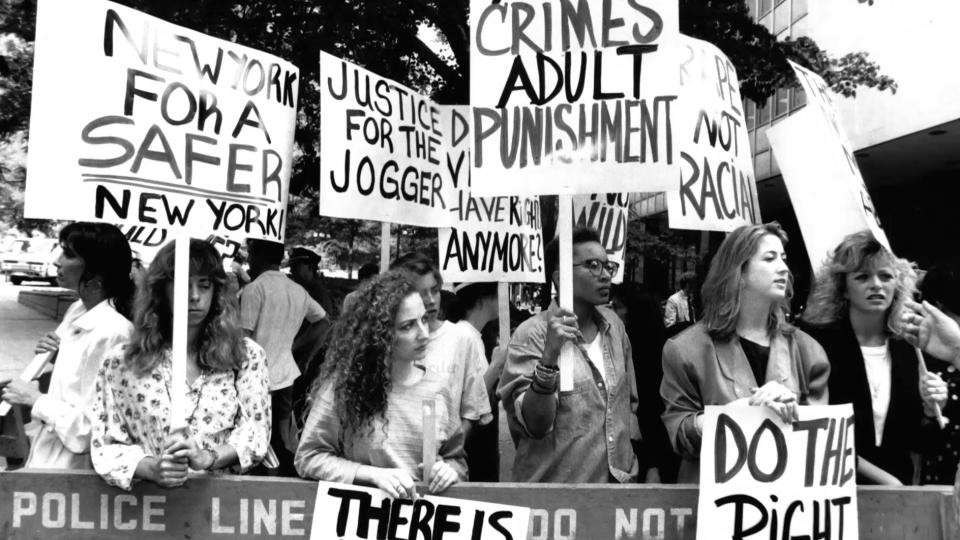

43. “The Central Park Five” (2012)

An infuriating look at one of the most offensive, racially-motivated cases in modern history, “The Central Park Five” provides a welcome exception to the usual Ken Burns routine. Part of its distinction comes from the other names associated with the project: Burns co-directed the movie with his daughter Sarah Burns and her husband David McMahon; the subject matter is partly derived from Sarah Burns’ book “The Central Park Five: A Chronicle of a City Wilding.” But there’s still a sense that the proverbial “Ken Burns effect” takes on new meaning — rather than zooming in on old images, Burns magnifies neglected facts to reveal a horrific miscarriage of justice.

The case in point is the scenario that led five Harlem teenagers to spend their young adulthood behind bars for a crime they didn’t commit. These teens were victimized in the wake of “The Central Park Jogger” incident in which a young woman was raped in Central Park; much of the city’s more prominent figures (including Donald Trump) honed in on the racist notion of “wildings,” a reductive term of youth gang activities, to explain the case. The directors gradually pull apart this notion and exonerate their subjects, but even as “Central Park Five” reaches some modicum of a happy ending, the sentiments behind the suffering these men endured in the public light amounts to a stunning modern tragedy. —EK

42. “After Tiller” (2013)

A Kansas physician whose deep belief in reproductive rights led him to become the medical director of Women’s Health Care Service at a time when it was one of the only three clinics in America that was willing to provide late term abortions, George Tiller was repeatedly targeted by right-wing extremists before his eventual assassination in 2009. Per its title, Martha Shane and Lana Wilson’s remarkable “After Tiller” plunges into the politically fraught health crisis that its namesake left behind as it follows the trials and tribulations (and bittersweet mercies) of the four doctors who vowed to continue Tiller’s work in the face of grave danger.

Opting to shine light on the perils of abortion providers — and abortion legislation — instead of turning up the heat on an already combustible situation, Shane and Wilson’s film eschews politics for the people who have to live with them. By empathizing with the extraordinary and heartbreaking circumstances under which a prospective mother would choose to deliver a stillborn fetus, this profoundly empathetic documentary reveals how obfuscating the rhetoric around abortion has become. It is, in its own gentle way, an urgent rallying cry for the preservation of a woman’s right to choose in the face of an unfathomable situation where everything else has already been taken from them. —DE

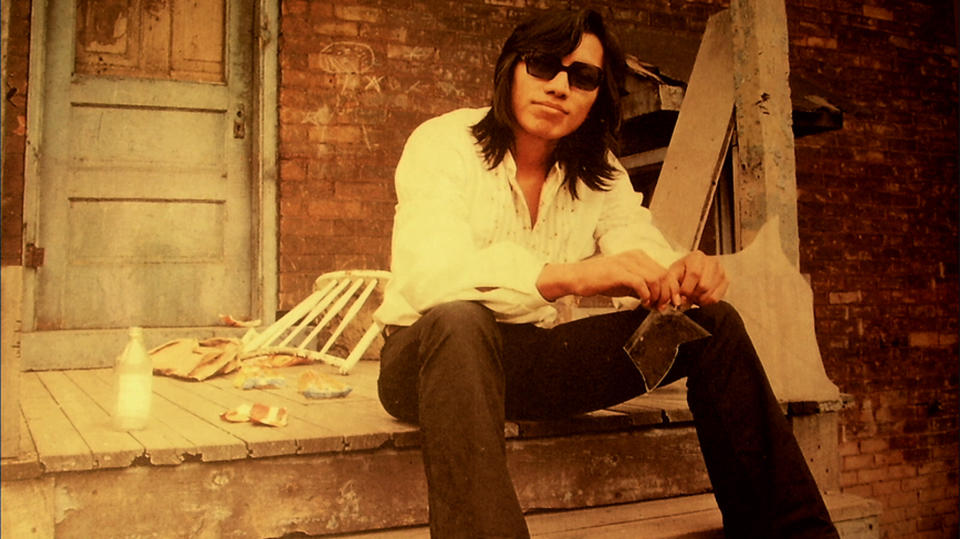

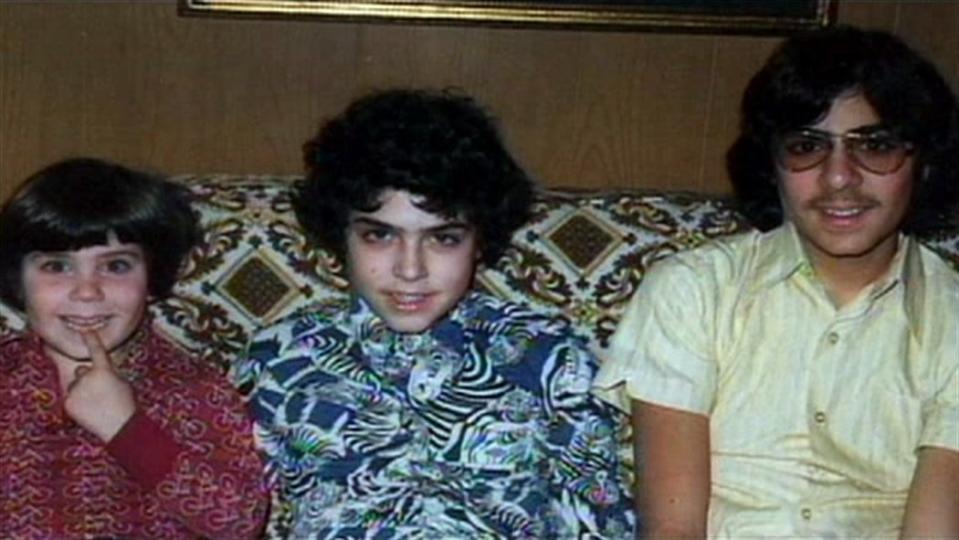

41. “Searching for Sugar Man” (2012)

When 1970s Mexican-American singer-songwriter Sixto Rodriguez faded from view, he’d never had much visibility in the first place. Typically known only as “Rodriguez,” the musician’s gentle pop tunes and activist spirit came through in a handful of albums that were barely noticed in the U.S. However, “Searching for Sugar Man,” documentarian Malik Bendjelloul’s remarkable chronicle of Rodriguez’s neglect on his home turf and unexpected stardom in South Africa, compellingly argues for his place in the canon of great American rock stars, whether or not he wants the spot.

Rodriguez’s music gives the movie a masterful soundtrack and explains its purpose all at once. His lyrics grapple with the plight of the working man, but swap political rhetoric for personal yearning. Bendjelloul tracks his subject’s life through a combination of testimonials from diehard Rodriguez fans and metropolitan landscapes to underscore the music’s evocative power. But it’s the South African context that gives “Searching for Sugar Man” its meatiest hook. For a quarter of a century — unbeknownst to most Americans, including Rodriguez’s original producers — the singer landed a massive following in the country where his humanitarian outlook provided an escape for many disgruntled youth struggling under apartheid, elevating him to the stature of a “South African Elvis.”

The director makes a convincing case for Rodriguez as a phantom rock star, no less valid than Bob Dylan, but never validated by the marketplace. “Rodriguez, as far as I’m concerned, never happened,” a former producer sighs, but the truth is more spectacular: Rodriguez simply made peace with his professional failings, and gained popularity without the aid of the industry. He was a hero who never chased the spotlight. —EK

40. “Minding the Gap” (2018)

Bing Liu’s “Minding the Gap” captures the transportive power of skateboarding — its power to take people out of their lives, even when they aren’t necessarily going anywhere — better than just about any other film ever made, but it would be terribly reductive to think of it as a “skateboarding film.” For Liu, the activity seems more like a means to an end than anything else. And his unforgettable documentary feature debut, which was filmed over the course of a decade, poignantly articulates all the ways in which that’s always been true for himself and his two closest friends.

For one thing, it got them out of their Rockford, Illinois homes, and away from the rotating cast of absent or abusive men who tended to roost in them. For another, it allowed them to make the world their playground in a down-on-its-luck pocket of the country where so many young men become products of their environment. The powerlessness Liu feels when one of his friends seems to fall into that trap is made intensely palpable to us through the viewfinder of his camera, and so is the freedoms that all three of them fight for; freedom from the inherited demons of socioeconomic disenfranchisement, freedom from families, and sometimes even freedom from themselves. In a young century that’s so far been overrun with coming-of-age stories, few have stuck the landing harder than “Minding the Gap.” —DE

39. “Faya Dayi” (2021)

Jessica Beshir’s acclaimed debut feature embeds itself in Harar, a city in Eastern Ethiopia. There, several communities exist that practice the custom of chewing khat, a plant that can induce hallucinations, for spiritual and religious rituals. “Faya Dayi” explores in stark black and white the impact that the plant has on the community. Beshir’s documentary premiered at Sundance in 2021, and was added to the Criterion Collection a year later. —WC

38. “Virunga” (2014)

Orlando von Einsiedel’s Oscar-nominated documentary is a riveting, up-close look at the ongoing battles between Congolese park rangers and poachers in Virunga National Park, a UNESO World Heritage Site in the eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo. In the years since its release, the movie has been optioned for a narrative feature adaptation by Leonardo DiCaprio’s Appian Way with a script by Barry Jenkins. It’s easy to see why Hollywood would show interest: In addition to a dramatic backdrop with clear heroes and villains, the movie also features lovable apes.

It’s here that some of the world’s last mountain gorillas rest, alongside a rich ecosystem of wildlife that includes prides of elephants and other exotic creatures, many of whom have become fodder for swarms of poachers. The director, who lived for months in a tent alongside the park rangers, captures tense interrogation sessions and shootouts as the drama careens through a series of confrontations, while chief warden Emmanuel de Merode fights to keep the gorillas safe. While the director includes sweeping bird’s eye views of the landscape to show the full extent of the park’s natural splendor, the movie derives much of its intensity from being in the thick of the situation rather than merely surveying it as an outsider. Few activist documentaries double as first-rate action-thrillers, but “Virunga” makes the case for conservationist efforts from one tense shot to the next. —EK

37. “Summer of Soul” (2021)

It’s hard to think of a single documentary in history that’s more of a surefire crowd pleaser than “Summer of Soul.” Questlove’s directorial debut investigates the political and cultural forces that created the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival: a month-long series of concerts in New York’s Mount Morris Park. The event is often nicknamed Black Woodstock, and the beautiful, unearthed and restored footage of the performances — from legends like Stevie Wonder, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone — puts the musical talent of the festival on full display; it’s hard not to stand up and cheer during Simone’s astonishing set, in particular.

If incredible music was all “Summer of Soul” had to offer, it’d be a good documentary; what makes it a great one is the context that Questlove provides, through newsreel footage and interviews with performers, about how the Civil Rights movement led to the festival, how it celebrated Black pride and unity, and how the erasure of the event from history was an erasure of Black history. The Harlem Cultural Festival is an astonishing achievement that needs to be remembered, and “Summer of Soul” helps ensure it’ll never be forgotten. —WC

36. “Dick Johnson Is Dead” (2020)

It’s hard to fathom how non-fiction stalwart Kirsten Johnson found a way to make a film that feels even more personal than her ultra-absorbing “Cameraperson” (which she stitched together from the leftover footage she had from decades of film shoots), but “Dick Johnson Is Dead” would be hard to fathom under any circumstances. A playful, bittersweet elegy for a man who’s still alive — and, as of May 2021, is still alive — Johnson’s mordantly hilarious documentary finds her trying to make peace with her father’s imminent death by staging violently elaborate visions of how it might come for him. An air-conditioning unit falling on his head as he walks down a New York City street. An absent-minded construction worker turning around too fast and accidentally slicing open Dick’s jugular with one of his tools. A tumble down the staircase of his house that ends with him face down in a growing pool of his own blood.

The concept could easily devolve into the stuff of a twee exercise in navel-gazing, but in so boldly confronting the many faces of death that are always watching us from the shadows, Johnson’s film is able to revel in the fullness of life at the same time that it threatens to slip away forever. —DE

35. “Capturing the Friedmans” (2003)

In 2003, Andrew Jarecki’s “Capturing the Friedmans” quickly became a landmark achievement in the history of non-fiction film, snatching up a Grand Jury prize at the Sundance Film Festival, generating massive buzz and heated controversy in the wake of its release, and eventually landing an Oscar nomination. The filmmaker’s dark investigation into the pedophilia charges against the late Great Neck resident Arnold Friedman and his teenage son Jesse, partially told through the family’s uncomfortably intimate home movies from the ’80s, captured the dissolution of an American family in extraordinary detail.

There are many ways to engage with this unsettling documentary thriller: It’s an exposé of the he-said, she-said dynamics that complicate virtually every sexual assault case, a treatise on the voyeuristic nature of home movies and what can happen when their initial function gets subverted, and an epic tragedy about the American dream gone sour. But more than anything else, “Capturing the Friedmans” is astonishing filmmaking that draws you into a seemingly comfortable family unit, takes a dark turn, and leaves you feeling as uncertain about the victims and the perpetrators as many of the people involved in the case. —EK

34. “The Mole Agent” (2020)

There’s a certain immersive thrill that comes from documentaries that hide themselves, and “The Mole Agent” epitomizes that appeal. Chilean director Maite Alberdi’s delightful character study unfolds as an intricate spy thriller, with a sweet-natured 83-year-old widower infiltrating a nursing home at the behest of a private detective. The plan goes awry with all kinds of comical and touching results, so well assembled within a framework of fictional tropes that it begs for an American remake. But as much as such a product might appeal to companies hungry for content, it would be redundant from the outset, because “The Mole Agent” is already one of the most heartwarming spy movies of all time — a rare combination of genres that only works so well because it sneaks up on you. —EK

33. “American Factory” (2019)

Veteran documentary filmmakers Steven Bognar and Julia Reichert’s Oscar-nominated short “The Last Truck: Closing of a GM Plant” tracked the final days an Ohio factory that left some 3,000 people without jobs. The Oscar-winning “American Factory” serves as a kind of sequel to that drama, revealing the strange odyssey of the company that moved in. The saga of Fuyao Glass America, a Chinese-run company that overtook the old GM plant and rehired thousands of locals, unfolds as a fascinating tragicomedy about the incompatibility of American and Chinese industries. Arriving in town as its saving grace, Fuyao instead brings a whole new set of bureaucratic problems and enterprising goals often lost in translation.

“American Factory” takes off two years into the factory’s arrival, as over 1,000 people have been employed by the glassmaker and optimism runs high. The company’s hawkish leader, the beady-eyed billionaire Chairman Cao Dewang, arrives at the facility beaming with pride — but it doesn’t take him long to start micromanaging every facet of the plant, leaving his English-speaking senior staff agape. As Cao wanders the grounds with a translator in tow, “American Factory” shifts from an optimistic portrait of a Chinese rescue mission to a dispiriting comedy of errors, like an episode of “The Office” for fans of “The World Is Flat.”

While the movie finds a natural end point, the saga of Fuyao Glass America is far from over. The payoff leaves something to be desired, but understandably so, as the very existence of this documentary sets the stage for a new phase of factory life unlikely to smooth out its troubles anytime soon. —EK

32. “Weiner” (2016)

Josh Kriegman and Eylse Steinberg’s tragicomic portrait of Anthony Weiner’s cataclysmic mayoral campaign ends with the filmmakers asking their subject a question that feels like it should be tacked on to the end of every documentary: “So why did you let us film you?” Weiner doesn’t (or can’t) respond, but we already know his answer: Because he can’t help himself. A painfully relevant portrait of human foibles, this is the story of a man who could have been great if he weren’t such a schmuck; it’s the old allegory about the scorpion and the frog, and we all drown at the end. Told through incredible fly-on-the-wall access and rounded out by an incredible cast of characters, “Weiner” is the rare documentary that you desperately wish had less to say about The Way We Live Now. —DE

31. Procession (2021)

Therapy is often an uncomfortable subject to watch on film, but the unconventional counseling seen in “Procession” is downright devastating to witness. Robert Greene’s Netflix documentary profiles six middle-aged men who all survived child sexual abuse from Catholic priests and clergy members, as they write and direct filmed reenactments of their trauma as part of a drama therapy exercise. The film weaves between the shorts the men develop and the emotionally grueling process of shooting them, and both the fiction and reality sections reveal substantial layers of how childhood abuse stays with and molds you. But the friendships and support the survivors develop add a touch of lightness to the devastating story; Greene isn’t afraid to leave in questions about the ethics of his doc in the final edit, and the film doesn’t try to swing for uplift or claim that the men are completely healed, but you get the sense they come out of the experience better than they started. —WC

30. “City Hall” (2020)

Legendary documentarian Frederick Wiseman directed and edited this mammoth 4-hour portrait of Boston, Massachusetts city hall. Consisting of footage taken between 2018 and 2019, the film tracks the day-to-day of the city’s then-mayor Marty Walsh and his staff as they contend with climate change action, housing issues, and Trump administration policies. The film, which was broadcast in the United States on PBS, was named the best film of 2020 by French magazine Cahiers du Cinéma. —WC

29. “Fire at Sea” (2016)

Gianfranco Rosi’s riveting non-fiction drama takes place on the Italian island of Lampedusa, where thousands of migrants are rescued from Africa throughout the year. (Others aren’t so lucky.) While the bracing footage of rescue efforts are enough to make the movie a terrifying peek beyond the headlines, Rosi compliments them with the portrait of Pietro Bartolo, a kindly doctor who treats new arrivals to the island and speaks to the lonely, DIY efforts involved in addressing a problem when the broader system falls short of solving it. Rosi juxtaposes these moments with the carefree exploits of a young boy who lives on the island, a stand-in for the innocence that much of the world experiences in relation to this global crisis. It’s harrowing filmmaking with a razor-sharp message. —EK

28. “Leviathan” (2012)

Harvard University’s Sensory Ethnography Lab has dedicated itself to pioneering new frontiers of immersive documentary filmmaking, and efforts like “Sweetgrass” and “Manakamana” have proven that there are any number of compelling ways of fulfilling that mission statement. But the outfit’s magnum opus remains 2012’s “Leviathan,” in which directors Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel provided a peerlessly immediate look at the commercial fishing industry by sticking GoPro cameras on the hull of a ship.

The footage they brought back to dry land is borderline hallucinatory, as viewers are plunged into a grey-blue word of frigid terror, every image overwhelmed by the raw elemental power of the world’s most indifferent work environment. The glimpses from inside the ship are almost as harrowing, as cock-eyed shots of a foul mess hall indicate that the ship’s crew are capable of creating a hellscape of their own. There’s vérité and then there’s vérité, and “Leviathan” remains a shining (if shivering cold) example of the latter — the film is such a transportive and tactile experience of working the high seas that it feels like it should end with a paycheck. —DE

27. “Kate Plays Christine” (2016)

On the morning of July 15, 1974, a Sarasota news reporter named Christine Chubbuck read through a few of the day’s top stories and then calmly shot herself in the head on live television. Footage of the (ultimately fatal) event has never been seen since, though a tape supposedly exists under a law firm’s lock-and-key. For “Actress” filmmaker Robert Greene, who has always been fascinated by the mythic power of images and the implications of creating them, Chubbuck’s performative suicide was an irresistible subject. He decided to recreate the missing video.

Casting actress Kate Lyn Sheil as Chubbuck, taking her down to the coast, and goading her to get into character, Greene’s characteristically self-reflexive and increasingly hypnotic film wedges fact against fiction until the two are subsumed by each other under the haze of the Florida sun. Richer, more compelling, and more aggressive than anything Greene had made before, “Kate Plays Christine” leverages a morbid historical footnote into an essential documentary about the ethics of exhuming the dead on screen. —DE

26. “Honeyland”

Tamara Kotevska and Ljubomir Stefanov’s two-time Oscar nominee “Honeyland” is a bitter and mesmerically beautiful documentary that focuses on a single beekeeper as though our collective future hinges on the fragile relationship between her and her hives.

But Hatidze Muratova is no ordinary apiarist. In fact, she’s apparently the last of Macedonia’s nomadic beekeepers, although — like every other bit of context in this strictly observational film — that detail is never made explicit. It doesn’t need to be: The more time we spend watching Muratova stick her bare hands into natural stone nests and sing old folk songs to her buzzing swarms, the more obvious it becomes that she’s one-of-a-kind.

Kotevska and Stefanov respect Muratova’s interiority, and don’t presume to know what she’s thinking. Their six-person crew lived on the lot beside her for three years, and some of the stray moments they captured — such as the one where Muratova sits inside the cold stone of her unelectrified hut and fusses over the exact color of her hair dye — hint at all the moments they never could.

When Hussein Sam, his wife, and their seven kids drive into Muratova’s neck of the woods in the film’s opening minutes, they bring a powder-keg of a plot conflict along with them. By reflecting Muratova’s relationship with her hives against the social contract that she’s formed with her mother — and that binds Hussein to his family — Kotevska and Stefanov shine a light on what the bees have always told us: They survive by serving each other. And if they ever disappeared completely, people would only have themselves to blame. —DE

25. “Don’t Leave Me” (2013)

If Jim Jarmusch made a movie about two alcoholic friends hanging out in the woods, it might look something like the Dutch documentary “Don’t Leave Me” (“Ne Me Quitte Pas”). Directors Sabine Lubbe Bakker and Niels van Koevorden’s hilariously touching portrait of bitter men drowning their sorrows in booze is the ultimate buddy comedy with brains. Shot in the isolated forests of Wallonia, in French-speaking southern Belgium, it manages a fascinating naturalistic tone that’s infectiously lighthearted without obscuring the downbeat quality of its subjects’ lives.

The filmmakers focus on the meandering exploits of middle-aged native Marcel and his slightly older Flemish chum Bob, whose destructive antics have cut them off from any source of companionship aside from each other. As they stumble through a seemingly abandoned world defined by their vices and self-deprecating wit, “Don’t Leave Me” marks the finest example of deadpan humor to come along in years. That’s largely because it never strays from an emotional foundation that makes Marcel and Bob so likable no matter how much they screw up. —EK

24. “Citizenfour” (2014)

“I am not the story,” says Edward Snowden to documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and journalist Glenn Greenwald in “Citizenfour,” but like Snowden himself, there’s nothing simple about that statement. Poitras’ bracing look at the former National Security Agency contractor, whose intel about government surveillance launched a firestorm of global inquiries following his exodus from the country in 2012, gives us everything we already knew about Snowden and his findings in a tightly-wound package — while hinting at a fascinating bigger picture filled with new information. “Citizenfour” would be a remarkable experience even if were simply a behind-the-scenes look at the biggest government leak in modern history, but Poitras also happens to be a terrific filmmaker, transforming Snowden’s paranoid world into a microcosm of our uncertain, fragmented times. —EK

23. “Man on Wire” (2008)

An appropriately playful portrait of Philippe Petit and his immortal wire walk between the Twin Towers, James Marsh’s “Man on Wire” is many things — a non-fiction heist movie, a good-natured attempt to reclaim the World Trade Center from its grim history, the inspiration for composer Michael Nyman’s greatest score — it is at heart the character study of a man who refused to heed the laws of nature.

Marsh presents Petit as a death-defying dreamer who views the world as his playground, an eccentric who’s willing to risk his life in order to restore some of its wonder, and his unbridled enthusiasm is deeply infectious (the most incredible part of Petit’s story might be that Werner Herzog didn’t tell it first). Where other people once saw a target, and where people now typically see a graveyard, Petit saw Manhattan’s most iconic monuments as his destiny, built only so that he could dance from one to the other on an August morning in 1974. Balancing his film as carefully as his subject balances his feet, Marsh’s thrilling doc looks back into the 20th century in order to soften the most grievous stain of the 21st. —DE

22. “Collective” (2020)

“Collective” starts as one of the greatest journalism movies of all time, and then it goes one step further, exposing democracy at war with itself. Romanian director Alexander Nanau’s bracing, relentless documentary tracks the aftermath of the 2015 fire that killed 64 people, hovering at the center of a system on the verge of collapse. And then it does, much like the flames that engulfed Bucharest’s Colectiv nightclub and sent the nation into a tailspin. “Collective” plays like a gripping real-time thriller, merging the reportorial intensity of “Spotlight” with the paranoid uncertainty of “The Manchurian Candidate” as it explores the national fallout of a tragedy that won’t let up.

Its initial hero emerges from an unlikely place: Sports Gazette reporter Catalin Tolontan and colleague Mirela Nega run the phones with an aggressive work ethic that would leave Woodward and Bernstein in awe, but it’s not just their story; Nanau makes the bold decision later on to switch focus to new minister of health Vlad Voiculescu, who’s tasked with leading a transparent overhaul of Romania’s dysfunctional medical system, even as he faces pushback at every turn. Juggling this dense assemblage of strategy sessions under the looming cloud of a national election, the movie provides a sobering window into the nature of democratic ideals within the swirling machine of systemic corruption. But it’s too fast-paced and too complex to feel like a pity party. “Collective” demonstrates the potential for moral courage to endure, under even the most dire efforts to snuff it out. No matter who runs the show, the work goes on. Let’s not forget that. —EK

21. “All That Breathes” (2022)

Shaunak Sen’s “All That Breathes” is a remarkably quiet and slow documentary, but that’s precisely what makes it so captivating. A portrait of two brothers — Mohammad Saud and Nadeem Shehzad — who run a veterinary clinic dedicated to treating black kite birds affected by the pollution of New Delhi, “All That Breathes” takes a meditative structure, documenting their bird rescue and treatment with a tranquil stillness. Hot button topics surround the film — climate change, the relationship between humanity and nature, anti-Muslim sentiment and violence in India — but Sen is more interested in exploring those themes through the brothers’ work than through talking heads. It’s an uncommon restraint to see in a documentary, and one that makes the brothers unglamorous, seemingly almost futile work resonate as real. —WC

20. “Cameraperson” (2016)

Kirsten Johnson opens “Cameraperson” with a note describing the project as “my memoir,” but it’s safe to say there’s never been a memoir quite like this one. Cobbling together footage from her 25 years of experience as a documentary cinematographer, “Cameraperson” offers a freewheeling overview of the people and places Johnson has captured over the course of a diverse career. More than that, the two dozen projects showcased here alongside original footage confront the process of creation. This is a collage-like guide to a life of looking.

Johnson’s credits range from risky exposés such as “Pray the Devil Back to Hell” and “Citizenfour” to lighter fare like last year’s New Yorker cartoon portrait “Very Semi Serious,” all of which surface in this dense global survey. But the disparate subject matter congeals around her implied presence in every scene. Soviet film theorist Dziga Vertov would surely approve of Johnson’s approach — an alternate title could be “Woman With a Movie Camera” — since it turns the idea of the camera into a vessel for studying the world. Though much of the material in “Cameraperson” is old, Johnson has undeniably created something refreshing and new. —EK

19. “Gunda”

More experience than movie, “Gunda” is a visionary case for veganism in black-and-white. Russian filmmaker Viktor Kossakovsky’s mesmerizing achievement removes humans from the picture to magnify the small moments in the lives of various farm animals, with his eponymous pig at its center. Over the course of 90 hypnotic minutes, his roving camera observes Gunda and her piglets, a handful of chickens, and a smattering of cows simply going about their lives on an unspecified farmland.

Devoid of music or any other obvious artifice, “Gunda” neither aims to document animal consciousness or anthropomorphize it. Instead, Kossakovsky’s fascinating non-narrative experiment burrows into the center of his subject’s nervous system, meeting the creatures on their own terms in a remarkable plea for empathy that only implores carnivores to think twice by implication. —EK

18. “At Berkeley” (2013)

Frederick Wiseman has made 11 documentaries since the start of the 21st century, and any one of them could have earned a spot on this list — he may be well into his ’80s, but the vérité legend is still at the very top of his game, and his gift for rendering massive institutions on a human scale has only grown more acute over time. Of all his recent work, however, “At Berkeley” stands alone. As massive and sprawling as anything Wiseman has ever made, this four-hour portrait of life on the famous university campus might seem daunting at first, but it quickly blossoms into a fascinating and accessible non-fiction epic about the sheer magnitude of sustaining a school of that size.

Strong on a micro level (footage of the robotics program is particularly fun) and even stronger when it broadens its focus to a macro degree, Wiseman’s film uses Berkeley’s budget crisis as a lens through which to comprehend culture as a living organism with an infinite number of moving parts. Through his impeccable eye, Wiseman makes every single one of them feel essential. —DE

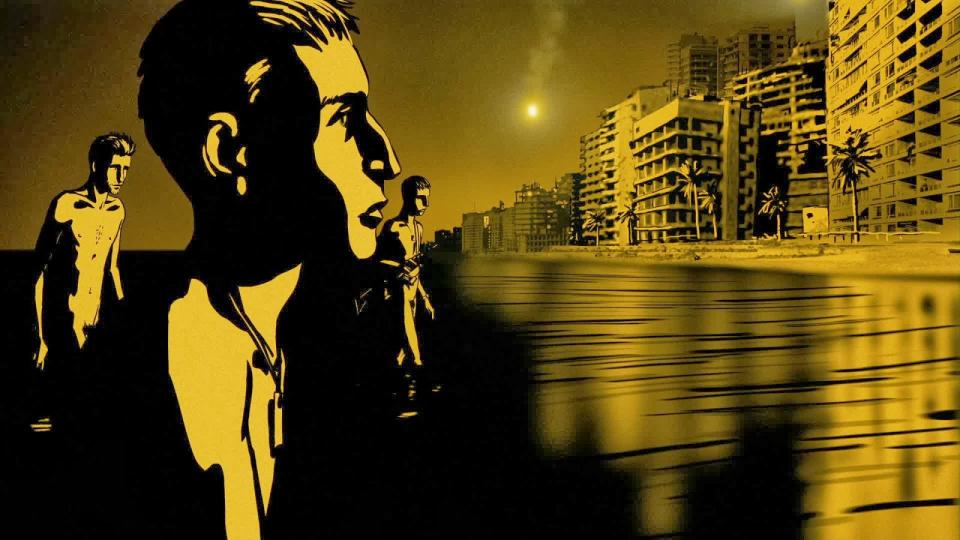

17. “Waltz with Bashir” (2008)

Ari Folman’s tortured masterpiece is a difficult thing to classify, and not just because an animated documentary sounds like such a contradiction of terms. No, “Waltz with Bashir” is such a strange bird because it exists on the highly contested border between reality and imagination — it doesn’t belong to fact or fiction, but rather the hazy middle ground of memory.

First and foremost a performative act of remembering, the film follows Folman as he thinks back on his time as a 19-year-old soldier on the Israeli side of the 1982 Lebanon War and tries to shine some light into the voids that have since formed in the darkest recesses of his mind. Visiting his old war buddies, shooting their conversations on HD video, and then layering those encounters in a dream-like skin of Flash animation, Folman transforms a guilt-stained memoir into a singular portrait of history and all the ways in which it haunts us. Any number of films have been called “unforgettable,” but “Waltz with Bashir” examines what that distinction really means, and in doing so becomes one of the few films to genuinely earn it. —DE

16. “Fire of Love” (2022)

A love story more romantic than most narrative features blazes at the heart of “Fire of Love”: Sara Dosa’s documentary about French volcanologists Katia and Maurice Krafft. A happily married couple, the two scientists’ love for each other was equaled by their love of lava, and the two spent their lives roaming the planet documenting volcanic eruptions through video footage, ultimately dying together in a 1991 explosion.The Kraffts’ archive of their volcanic expeditions provide the bulk of the documentary, and the footage is gorgeous, putting the audience closer to molten lava than anyone would ever typically want to be. And Miranda July’s narration is a lovingly curious account of the two eccentric individuals, who frequently risked their lives in pursuit of the shared passion that united them. The film is being adapted into a narrative feature, but it’s hard to imagine a fictional account with as much heart and heat in it as “Fire of Love.” —WC

15. “Exit Through the Gift Shop” (2010)

From the moment elusive street artist Banksy appears on camera in “Exit Through the Gift Shop,” something seems fishy. With his face obscured by shadows and his real voice rendered unrecognizable by mechanical distortion, Banksy remains the mysterious figure he has always been. In “Exit,” the context of his anonymity shifts from public vandalism to cinema, an equally appropriate venue for creative tomfoolery. (Other critics have aptly compared it to Orson Welles’s 1974 essay film “F for Fake.”) Although the movie ostensibly tells a true story, much of what appears on screen raises the possibility of a trickster behind the scenes, expanding its allure.

A blend of talking heads and dubious home video footage, “Exit” centers on relentless video diarist Thierry Guetta, a jolly Los Angeles-based Frenchman whose aimless interest in shooting street artists led him to become chummy with Banksy himself – or so we’re led to believe. Non-fiction purists can easily dream up conspiracy theories about the nature of the movie and the category where it belongs (most likely it’s some sort of hybrid). But the very nature of uncertainty in “Exit” is what makes it such a masterful inquiry into the sense of authority associated with the creative process. —EK

14. “Grizzly Man” (2005)

It’s interesting that, after Werner Herzog had already been churning out essential cinema for more than 30 years, this was the movie that turned the German iconoclast into a household name (and sparked his eventual transmutation into an internet meme). Maybe it’s because self-fashioned bear enthusiast Timothy Treadwell was the perfect Herzog hero, a fatally sincere eccentric whose hubris led him to defy nature at his own peril and convince himself that the world could reciprocate his love for it. Maybe it’s because his best friend was an adorable fox. Or maybe it’s because “Grizzly Man” contains one of the ultimate Herzog moments, a scene that brilliantly encapsulates so much of what there is to love about one of the most fiendishly gifted self-mythologizer in movie history.

If you’ve seen the film, you’re already thinking about the passage in which the director visits one of his subject’s ex-girlfriends and listens to audio tape from the day that Treadwell was mauled to death. He immediately implores the woman to destroy the recording. His reaction, delivered in the unflappable drone of Herzog’s hypothermic speaking voice (which always sounds like it’s lulling you towards death), obscures the documentary reality of raw data while simultaneously emboldening the story it leaves behind. It’s a moment of extreme showmanship that deepens our connection to the incident without betraying its integrity. It’s the “ecstatic truth” in all its morbid glory, and it’s impossible to forget. —DE

13. “Bowling for Columbine” (2002)

Michael Moore’s shtick has definitely started to wear a little thin over the years, and recent efforts like “Where to Invade Next” and his election quickie “Michael Moore in Trumpland” have helped to cement the impression that the documentary world has outgrown the filmmaker whose work made it so appealing to the masses. Once upon a time, however, Moore was something of a blue-collar visionary, and his “aw shucks” everyman appeal still felt like it could pierce through the veil of America’s biggest problems by addressing them with a careful mixture of humor, outrage, and accessibility. If “Bowling for Columbine” remains his most urgent film, it’s not only because our country’s gun epidemic continues to go unchecked, but also because the shaggy firebrand has never been so indignant, nor armed with such a concrete argument.

From antagonizing Kmart to “ambushing” Charlton Heston and strolling through idyllic Canadian suburbs in order to illustrate America’s trigger-happy paranoia, Moore’s rhetoric is characteristically cartoonish, but it all contributes to a bulletproof case against a toxic culture of fear that grows deadlier by the day. —DE

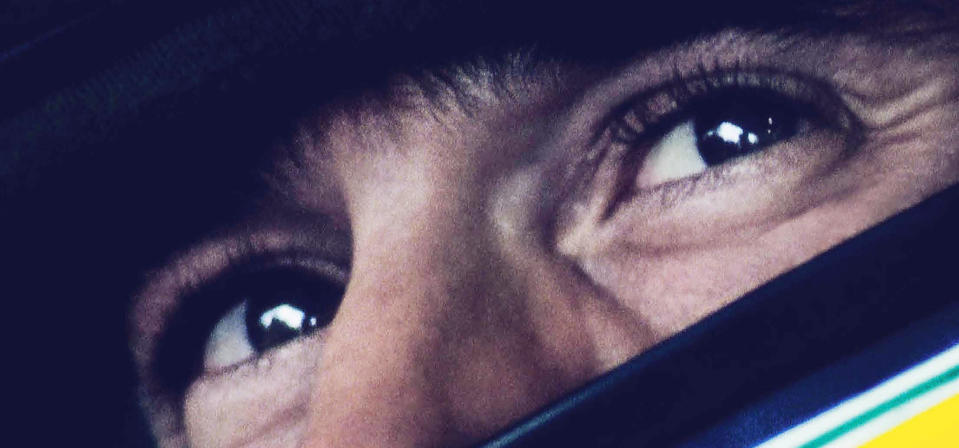

12. “Senna” (2010)

Asif Kapadia’s documentary traces the life and career of Ayrton Senna: one of the most successful car racers in the history of the sport. Eschewing contemporary interviews and narration in favor of home videos and archival racing footage, “Senna” places the audience straight in the Brazilian racer’s career as he rises to the top of Formula One before his tragic death in a 1994 race. For the film, Kapadia received a Sundance award, and won the BAFTA for best documentary. —WC

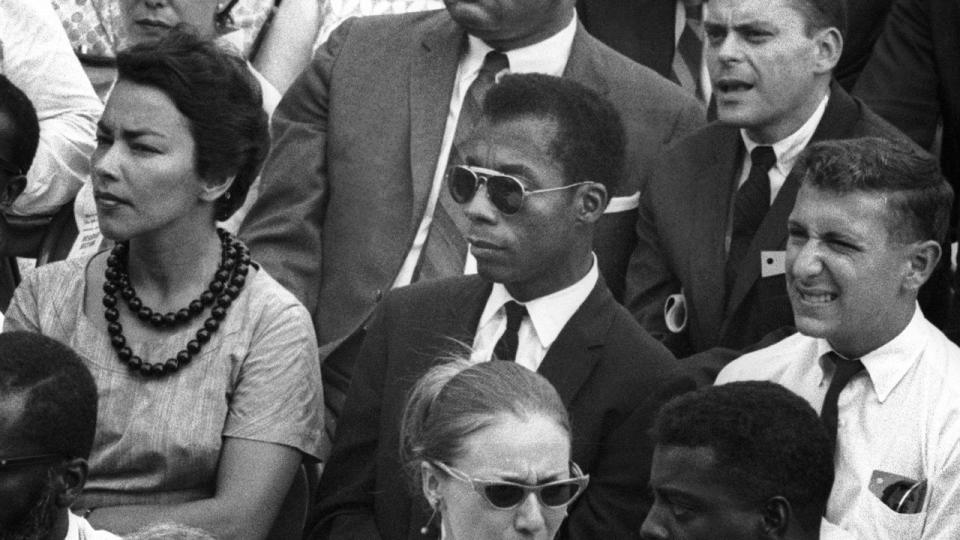

11. “I Am Not Your Negro” (2016)

“I Am Not Your Negro” operates on many levels at once: It’s not only a fresh vessel for James Baldwin’s own analysis of black life in America, but a platform for his assessment of other great thinkers who informed his views. Raoul Peck, an undervalued Hatian filmmaker who has shifted between narrative and documentary projects for nearly 30 years, uses a remarkable foundation for this sweeping exploratory piece: a 30-page manuscript Baldwin wrote in 1979, as part of an uncompleted book project that delved into the lives of Medger Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. All three activists died before they turned 40; Baldwin worked alongside, then outlived, all of them.

The movie injects Baldwin’s voice through a voiceover performance by Samuel L. Jackson that’s one of his very best performances in ages, while Peck shifts between archival footage of his four subjects (including Baldwin) and contemporary moments to throw the timeless resonance of Baldwin’s words. It’s at once a perceptive history lesson and a resurrection. —EK

10. “The Look of Silence” (2015)

When it was first announced that Joshua Oppenheimer was making a second film about the Indonesian genocide, it may have been natural to expect that his follow-up would be a glorified assemblage of B-roll or a mess of footage that he hadn’t been able to fit into “The Act of Killing.” Needless to say, that ultimately wasn’t the case. “The Look of Silence” is every bit as searing and essential as the film that preceded it. Switching his focus from the perpetrators of mass murder to the survivors, Oppenheimer hones in on an optometrist named Adi whose brother was killed in the slaughter. Leveraging a classic literary device that has previously been used to great effect in novels like “Slaughterhouse V,” the film follows Adi as he visits the men responsible for his suffering, this impossibly stoic figure remaining calm as he (quite literally) clarifies the world for the people who have bloodied it beyond recognition.

Intimate where “The Act of Killing” was flamboyant, and deeply bereft where Oppenheimer’s previous documentary was largely shellshocked, “The Look of Silence” is an eye-opening addendum to an atrocity that might be forgotten by now if not for the people who are still listening for its echoes. —DE

9. “Stories We Tell” (2013)

Until she made “Stories We Tell,” Sarah Polley was best known as an actress and narrative filmmaker, but this personal documentary consolidates all of Polley’s talents by blending intimacy and intrigue to remarkable effect. Part of the reason why “Stories We Tell” works so well is that at first it doesn’t seem like it should. Setting up interviews with her father, Michael, in addition for various family and friends, Polley embarks on an account of her actor-mother Diane, who died of cancer when Polley was still a child. While obviously heartfelt, the drama lacks an immediate hook for those unacquainted with Polley’s personal history, and she doesn’t back away from it. “Who the fuck cares about our family?” her sister asks, establishing a challenge that Polley cautiously navigates for the first 45 minutes before reaching a point where the allure is self-evident.

Even before then, however, “Stories We Tell” is a fluid, engaging memoir by virtue of its construction. Polley apparently spent five years threading together conversations with Michael in addition to her other relatives and friends, and the effort shows. Coming full circle, the director eventually turns the camera on herself, but avoids coming across as mopey or narcissistic. Instead, the storyteller enters the story in order to understand its significance. “The crucial function of art is to tell the truth,” she’s told, but she posits her mission as an attempt to find “the vagaries of truth” and ultimately leaves us with a slew of ambiguities. By the end, only a handful of certainties have bubbled to the surface, none more affecting than the case for the movie’s existence. —EK

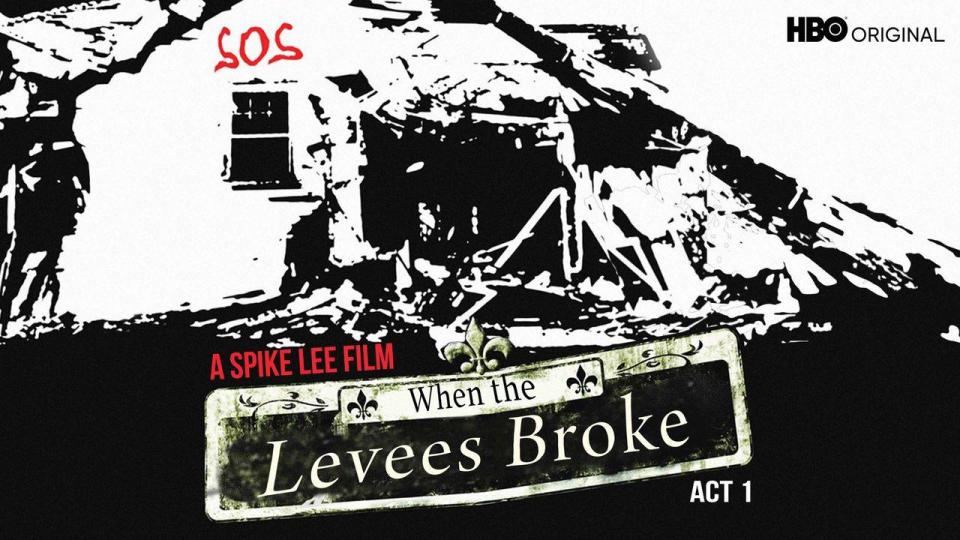

8. “When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts”

America has been through a lot of traumas in the 21st century, from 9/11 to Donald Trump and the pandemic. No filmmaker has addressed them all with more pointed insight than Spike Lee. However, none of his timely projects has done more for magnifying sorrow, loss, and the resilience of communal spirit than this sprawling HBO documentary, a definitive look at the destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina on the impoverished, mostly Black residents of New Orleans. With Terence Blanchard’s mournful score as its guide, “Levees” spend its four hours tracking every angle on the disaster through the eyes of the people most impacted by the damage.

The result combines interviews with dozens of locals, politicians, and other figures to combine a harrowing survival story with first-rate journalistic exposé. The movie details precisely how the apocalyptic impact on New Orleans was caused by engineering failures, how rescue and recovery efforts mainly turned on the efforts of grassroots activists, and why so many survivors were left stranded in the aftermath. Lee’s cameras take us into flooded homes and jazz clubs, careening from jolting images of floating corpses to overpacked evacuation centers. But the movie is not devoid of hope: Through the power of music and the strong-willed personalities who barrel through each scene, “When the Levees Broke” is an epic testament to the power to rebuild in trying times, and one of Lee’s most emotional and important filmmaking undertakings in a career loaded with them. —EK

7. “Time” (2020)

When an investor pulled out of their planned hip-hop clothing store in 1997, Louisiana couple Sibil “Fox Rich” Richardson and her husband Rob felt they had no choice but to hold-up a branch of the Shreveport Credit Union. It didn’t go well. Fox was sentenced to 19 years in jail, while Rob was given 65. Upon being released after 36 months in order to raise the couple’s six children, Fox began documenting their lives on grainy MiniDV so that Rob could watch his family grow up from behind bars. Almost two decades later, as the prospect of Rob’s early release began to seem possible, filmmaker Garrett Bradley began editing Fox’s footage into some of her own.

Swirling 21 years into an 81-minute slipstream that doesn’t juxtapose the pain of yesterday against the hope of tomorrow so much as it insists upon a perpetual now, Bradley’s monumental and enormously powerful documentary flattens time in a way that contextualizes mass incarceration on the largest of continuums. Both a harrowing story of one family’s perseverance and also a liquid history that streams together centuries of Black subjugation until slavery and the prison-industrial complex become two separate brooks that feed into the same river, this staggering film inverts the notion of “doing time” in order to crystallize an achingly human portrait of what time does to us. —DE

6. “Faces Places” (2017)

Agnès Varda, then 88 years old, may have been losing her eyesight when she partnered with the street artist JR for “Faces Places” in 2017, but her creative vision had never been clearer. And while this enormously funny, life-affirming, and altogether wonderful film would prove not to be her last — the summative “Varda by Agnès” followed in 2019, premiering just a few months before her death — it is nevertheless haunted by wistful notions of finality and impermanence.

The premise is simple: Varda and JR tour the French countryside in a mobile photo booth, inviting the people they meet in each bucolic village to pose for mural-sized snapshots that are then printed out and pasted onto the environments their subjects call home. The results are as unpredictable and coyly bittersweet as life itself, as Varda — working on a canvas big enough to fit all of the ideas that she was still dying to express — reflects on the power of the images we leave behind. Alas, nothing lasts forever, and Varda doesn’t hesitate to confront the sad truth that real life is often less fulfilling as it looks in the movies. At the same time, Varda’s films, and “Faces Places” in particular, endure as invaluable reminders that it doesn’t always have to be. —DE

5. “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” (2022)

Nan Goldin was born to have a documentary made about her. The photographer and activist is the type of singular presence — flinty but warm, witty and insightful, radical and dedicated to her causes — that makes for a good lead, and “All the Beauty and the Bloodshed” is a perfect portrait of the woman and her work. Interspersed with sections, told in Goldin’s narration and her photography work, chronicling her background and involvement in AIDS activism, Laura Poitras’ documentary centers itself around Goldin’s ongoing work during the opioid crisis, as she targets those responsible for the overprescription of OxyContin and the art world that continues to support them. Both Goldin’s past and her current campaign make for fascinating stories, and as told by the woman herself, they’re rousing celebrations of fighting against the injustices around you. —WC

4. “Flee” (2021)

Animated documentaries are a small but potent subgenre, and few films make as good use of the medium as “Flee.” Jonas Poher Rasmussen’s film tells the life story of his friend Amin Nawabi (an alias created for the movie): an Afghan man who fled his home country as a refugee when he was a child following the outbreak of conflict in the region. The experiences that eventually brought Amin to Denmark are painful and still weigh on him as an adult, and the film sees him share his story with Rasmussen and his partner for the first time. Aside from archival footage, the entire film is animated reconstructions of both Amin’s past, and his present life.

The animation serves a few purposes for the film: it helps keep Amin anonymous even as he shares his story with the world, but the dreamy, slippery art style and the occasional forays into abstraction are perfect for the story, portraying the fear, nostalgia, and longing within Amin’s account of the past. Once you watch “Flee,” you might wonder if most documentaries should be animated. —WC

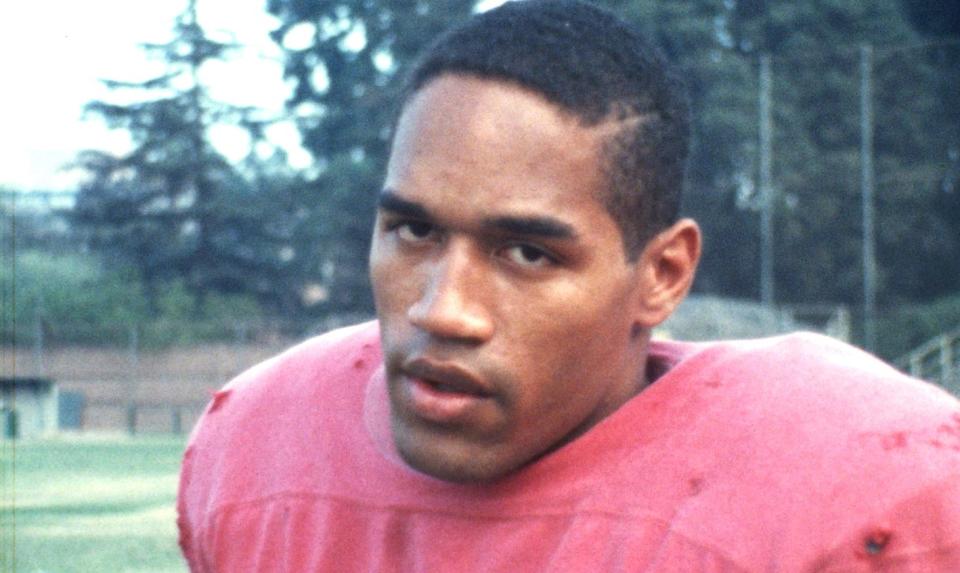

3. “O.J.: Made in America” (2016)

Ezra Edelmen’s monolithic, eight-hour documentary contextualizes O.J. Simpson’s place in American history, crafting an indisputable argument as to why the Juice’s celebrity — and his crimes — have made him the perfect lens through which to comprehensively explore the role that race continues to play in this country. It’s no secret that Simpson’s murder trial was never just about the deaths of two innocent people, but this incredibly well-sourced and hypnotically compelling time capsule does a brilliant job of locating the iconic event in a continuum of oppression.

Beginning with his subject’s days as a college football star, Edelmen walks us through the steps of a uniquely American life, exploring in unprecedented depth and detail how Simpson “transcended” blackness, and what that meant (and continues to mean) for a nation that sees color as acutely as ever. Is it a movie? Is it a TV show? It doesn’t matter, “Made in America” is essential viewing all the same. —DE

2. “This Is Not a Film” (2011)

By striking him down, the Iranian government made Jafar Panahi stronger than they could have possibly imagined. Already one of his country’s leading filmmakers before he was baselessly arrested for crimes against and sentenced to house arrest, Panahi took full advantage of his confinement, and proved that some artists are at their best when backed into a corner. Famously smuggled to Cannes on a USB stick that was buried inside a cake, “This Is Not a Film” is perhaps cinema’s greatest example of turning lemons into lemonade. Most of the movie consists of Panahi walking around his Tehran apartment with an iPhone in his hand, the great director growing stir-crazy as he talks through the script for his next project (eventually going so far as to diagram the sets on his floor), listens to the fireworks outside, and chats with the little boy who comes by to take out the trash.

Panahi, however is no stranger to self-reflexivity, and every second he’s on screen contributes to the remarkable performance at the heart of his protest. He may insist otherwise, but this is very much a film, one whose innate deficiencies only serve to sharpen this piercing glimpse at modern Iran. What begins as a rebuke to censorship ends as an incredibly moving statement about the value of artistic expression. —DE

1. “The Act of Killing” (2013)

Joshua Oppenheimer’s horrific look at the reverberations of the Indonesian genocide of the 1960’s adopts a terrifying perspective and never flinches: The filmmaker cedes screen time to the practitioners of military torture and lets them reenact their accomplishments. At once subversive and powerfully inquisitive, the movie probes the essence of evil by giving it the floor, and lets its vile subjects convict themselves.

“The Act of Killing” is one of the most unsettling movies ever made in part because it’s so audacious, allowing its subjects to produce exuberant musicals and fantasy productions glorifying their efforts as if dragging us into the center of their psychosis. Oppenheimer doesn’t exactly come up for air, but he does find a memorable road to getting real, when one of the men finally grapples with the horrific nature of his deeds and words fail him. By that point, audiences can relate. —EK

Best of IndieWire

Quentin Tarantino's Favorite Movies: 61 Films the Director Wants You to See

Martin Scorsese's Favorite Movies: 82 Films the Director Wants You to See

Sign up for Indiewire's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News