The 50 best TV shows of 2023: No 9 – The Sixth Commandment

Once in a while a drama gets under the skin so deeply it stays with you. No, in you. Frame after searing frame. The Sixth Commandment, written by Sarah Phelps and directed by Saul Dibb, was the most gut-wrenching example of the year. Perhaps the decade. In four harrowing, nigh-on unbearable episodes it took a genre often prurient, insensitive and morally dubious, and gracefully upended it. The Sixth Commandment was true crime that focused on the victims, though even to use that word feels like a thoughtless reduction. What it gave was a dignity rarely afforded, neither on screen nor in life, to people whose lives are destroyed by crime.

Those people, primarily, were Peter Farquhar (Timothy Spall), a retired Stowe schoolmaster, and his neighbour Ann Moore-Martin (Anne Reid), a retired headteacher. One after the other, in 2014 and 2017, they were befriended by a young churchwarden, Ben Field (Éanna Hardwicke), who inveigled himself into their lives. He read bible verses with them. Helped in the garden. Cooked for them. Moved in. Then he told them he was in love with them. After they had changed their wills in his favour, Ben proceeded to gaslight, humiliate, mentally torture and poison them. He murdered Peter, and attempted to murder Ann. After a Thames Valley police investigation and criminal trial in 2019, Field was sentenced to life imprisonment.

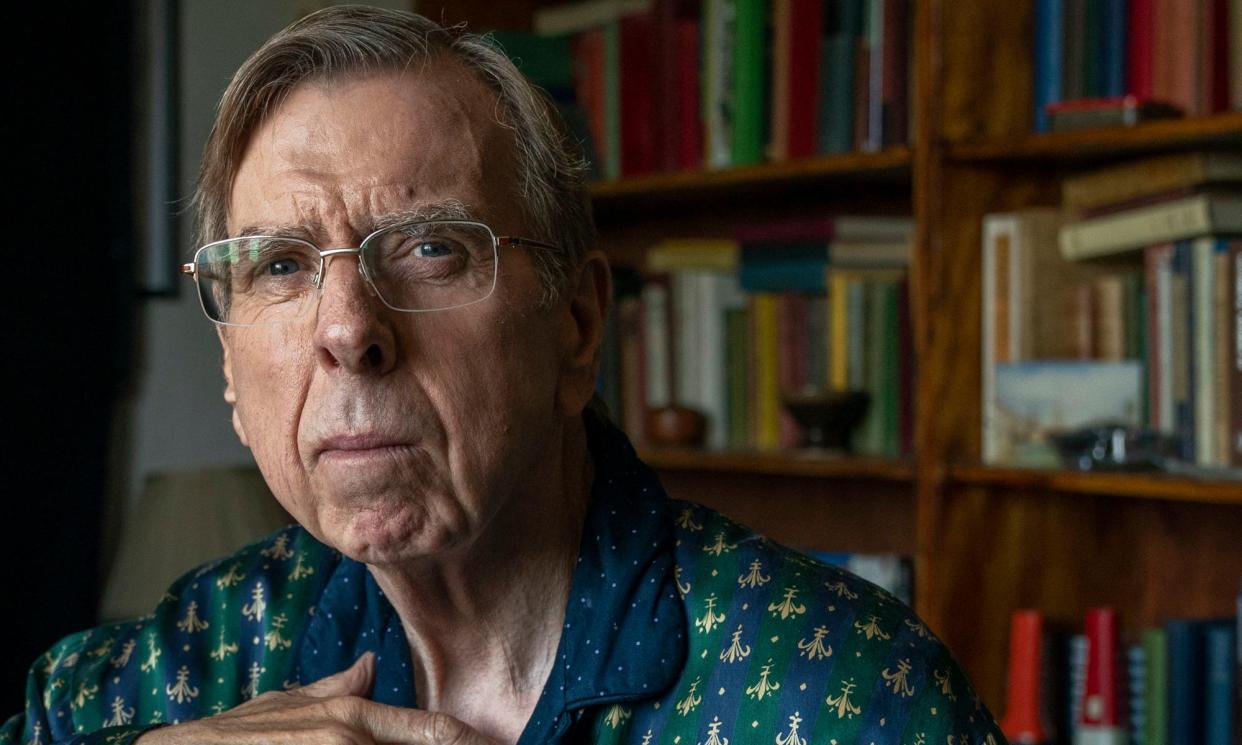

It was a drama of two distinct halves – intimate character study/police procedural – that coalesced flawlessly. The first two episodes centred on Peter, then Ann. Spall, in a career-best performance, embodied Peter with an exquisite tenderness. You could see his three decades working with Mike Leigh in the stoop of his gait, the way he deadheaded a rose or washed a cup at the kitchen sink. He imbued Peter with moral and physical fastidiousness, longing, self-loathing and terrible shame. Here was a man who’d spent a lifetime struggling to accommodate his homosexuality into his Anglican faith. An attempt that, played by Spall and penned by Phelps – a writer at the top of her game – was portrayed not as futile, but as central to his selfhood. “It’s never pornography; that’s not what I want,” he confessed to a friend of his reluctant habit of looking at pictures of men hiking in shorts. “Even my deviance is pathetic.” On the night of their secret betrothal, he confessed to Ben that he didn’t want sex. All he wanted was “to hold and be held”. How utterly heartbreaking.

Ann, just as beautifully played by Reid, was equally loving, religious – Catholic in her case – and, as her devoted niece Ann-Marie put it, “just good”. But their kindness was never beatified. Rather, it was part of the reason they were vulnerable to Ben’s lies. Not because they were gullible, frail or alone – though they were, like so many elderly people in this country, lonely – but because they were believers. In God, humanity, and, perhaps above all, love. This was what made The Sixth Commandment so upsetting to watch. This is why we must honour them.

Set in the sleepy parish of Maids Moreton, Buckinghamshire, The Sixth Commandment was masterfully directed by Dibb, a man who clearly just gets Englishness like great novelists do and can evoke its spirit with the yellowing of late summer light or the boiling of a kettle. I can’t wait to see what he and Phelps do next. Rewatching The Sixth Commandment (and it was even more distressing second time round) I was struck by how many lingering closeups there were of hands. Ann stroking Ben’s arms as he read John Donne to her in bed. Peter’s hand gripping a wall in hallucinogenic terror. Peter’s sister-in-law taking Ann’s traumatised niece by the hands in the final scene and telling her “you stopped him”.

The Sixth Commandment was about them, too: the families shattered by incomprehensible cruelty, the detective pulled out of retirement for one last case, the junior officer who slept on the office floor so he could trawl Peter’s diaries through the night, the barristers bantering on the first day of the trial. It was also about the ways we live, how we view and care for the elderly people in our lives, and the courage love takes. What it’s not about, ultimately, are the perpetrators. Ben’s motives – beyond his god complex, sadism and sociopathy – are never examined, nor is his back story revealed. Same goes for his accomplice, a magician from Cornwall called Martyn. Some viewers may have found this lacking. But The Sixth Commandment – which was extensively researched and dramatised with the full consent of both families – turns away from Ben and Martyn as a mark of respect. I respect it deeply for that. It is a masterclass in what true crime can do, and I won’t ever forget it.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News