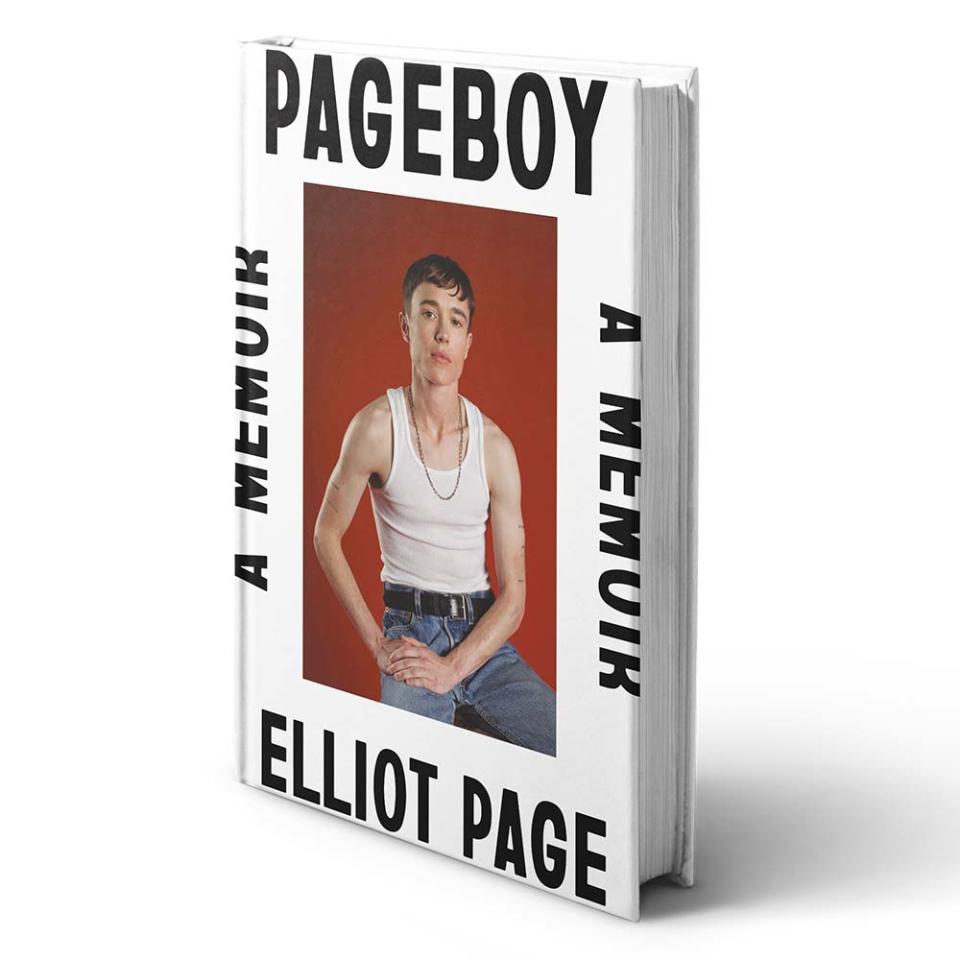

“I Have This New Ability to Sit With Myself”: How Elliot Page Made the Journey to Tell His Story in His Own Words

In the opening chapter of Elliot Page’s memoir, Pageboy, he writes about visiting a gay bar for the first time. He was 20 years old; it was the summer before 2007’s Juno premiered, about a decade and a half before he would come out as trans. “Shame had been drilled into my bones since I was my tiniest self, and I struggled to rid my body of that old toxic and erosive marrow,” Page writes. “But there was a joy in the room, it lifted me, forced a reaction in the jaw, an uncontrolled, steady smile.” Page never imagined he would write a book, but when the opportunity (and the self-assurance) came, the words flowed.

“I have this new ability to literally sit with myself and make things,” Page told THR over Zoom a few weeks before the memoir hit shelves. “I could never do that before [coming out].”

More from The Hollywood Reporter

'Burn It Down' Explores 'SNL' and Its "Culture of Impunity" (Exclusive Excerpt)

Martin Amis, Author of 'London Fields' and 'Money,' Dies at 73

The memoir tracks pivotal moments in the actor’s life, from childhood (in Nova Scotia) and a simultaneously successful and tumultuous entrée into Hollywood to his coming out as gay, and then later trans, on a public stage. “As you can see, I’m slightly nervous,” he says with a laugh. “But it’s thrilling and meaningful that people might connect to elements of my journey. I’m realizing that, ‘Oh, maybe people will read this book.’ ” Page describes what it was like to tell his story in his own words and what he learned after the creative team of Flatliners pressured him into performing a dangerous stunt.

Can you talk a bit about your decision to write a book — why a book, and why now?

The idea of writing a book would come up in the past and I would shove the idea aside, saying no, I don’t think the timing is right. But mostly, I did not think that it was possible for me. There’s been many a time I’ve looked at a book and thought, “I don’t understand how someone can do that.” But I met with my literary agents, who had been encouraging me to at least write a proposal — I remember I walked back to my apartment afterward and I sat down and had this stream of consciousness in which I wrote that first chapter, “Paula.” The final version in the book is not that different to how it came out. And I seemed not to be able to stop after that.

You write candidly about the ways that coming out fractured — for a time — your relationship with your mother. Was that a hard decision?

I definitely went through a process of deciding how much [of my personal life] to write about. The journey with my mom felt important to share because so many queer and trans people have a similar experience, and I hope that in talking about it vulnerably and honestly as possible it can help people feel seen, or show that it’s possible for people to change. But the experience of writing those moments only helped my mom and I get closer.

Did you let her read an early copy?

She hasn’t read the whole book, because there are moments in it where I’m like, ” Mom, you might not want to see that. (Laughs.) But the first thing I shared with her was that “Paula” chapter, and her response was to well up, and she sat back and said: “Your words, they sound like music.” That was so sweet, and she was so cool about it all. And talking to her before writing about her helped me learn a lot about her life and things she went through that I don’t think I would have learned otherwise.

Was there anyone else that you wanted to make sure was OK with what went into the book? I noticed that you named some people but left others anonymous.

I wrote about Ryan, my ex, and that whole story of our breakup. We’d already reconnected to a degree, and we’re friendly now, but that process made us much closer. We got to talk about that experience, and in looking back I was able to acknowledge my own behavior versus just being angry and self-righteous. That’s a really humbling part of writing the book — reflecting back on my own role in things. It’s been healing, and I’m grateful to her for that. I hope that when people read it they feel a degree of honesty and openness that I really wanted to put out there. I’ve been thinking about what it is about our culture that makes us not want to share this. I hope that question resonates with people.

When you describe our culture’s inability to discuss vulnerable topics, do you think of it as a uniquely American problem, or is it just as bad in Canadian culture?

That is a fantastic question, and I don’t think it’s much different in Canada. (Laughs.) I often think of that Rebecca Solnit book, The Mother of All Questions, where she asks what stories aren’t you telling, and why aren’t you telling them?

You write about some of the bad experiences you’ve had on set, whether it was discomfort with the way men in power treated you or being pressured into those dangerous stunts during Flatliners — do you think that actors have more autonomy now? Have things improved on set?

I don’t really know how different it is. It is so much about power. I am in a position on the set I work on [Umbrella Academy] where people probably are not going to try and fuck with me. I’m at a place where I’m not going to put up with anything. None of that means it’s gone away, of course, it’s just gone away for me because I’m in a different situation in my career. That shouldn’t be the case, obviously, we should all be treated with the same dignity and respect and care on film sets, and particularly if you’re young. I do know that I always feel protective when young people are on set — I wonder about their experience and I want them to not feel taken advantage of.

Do you think the younger generation is more educated about knowing their rights and boundaries, and are able to stand in their power? I think about Melanie Lynskey describing the Yellowjackets set, where she came in ready to be quite protective of the younger actors and them not needing her protection …

It does seem like people are learning about that at a younger age, but you never actually know what’s going on with someone. I’m sure when I was making Hard Candy [at 17] I seemed relatively self-assured and in control, and that it seemed to others that I had a good experience. It’s so insidious that you just never know.

What do you see as the turning point for yourself, where you were able to feel more in control and autonomous on set?

Well, I’ve had lots of these awful situations. Granted, it was the kind of behavior that I don’t think would be allowed to happen now — I had experiences with toxic, abusive people who are doing stuff right out in the open for everyone to see. And then you say something about it and end up being the one who is reprimanded. Maybe it’s top of mind because I wrote about it, but I do think my time making Flatliners [2017] was probably the last time that I thought, absolutely not.

How does the current wave of anti-trans legislation change the stakes for the publication of this book?

It’s interesting timing. Our lives and bodies have always been politicized, but we’re in a much scarier time. But it’s important for me to say that this is just my story. I do not represent most of the trans experience — I have privilege and resources and access to health care. And even with that, what I’ve been through is not fucking easy.

Your dog, Mo, gets to be the center of attention for a few chapters — will he be coming on your book tour?

He’s going to come on the North America tour, because I think at the end of some of those days I’m going to need to snuggle my little guy. He is just such a ball of love, and I’m the luckiest person. I don’t know what I’d do without him.

Interview edited for length and clarity.

A version of this story appears in the June 7 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Yahoo News

Yahoo News