Actress Ashley Grace: Fashion Photographer Raped Me During Shoot

In September of last year, former model and actress Ashley Grace posted a simple Instagram story: a leafy green tree shining in the sun, a clear blue sky behind it. Over the top, in black-and-white typewriter font, she wrote, “To every rape victim that is retraumatized by watching society debate and focus their attention on what is going to happen to the RAPIST, I see you.” She finished it with a heart emoji.

The story could have gone largely unnoticed: the message was vague and Grace’s Instagram following modest. But the timing was conspicuous. She posted it one day after a Los Angeles judge handed down a lengthy sentence to actor Danny Masterson, who had been convicted of raping two women—and who co-starred on the TV series That ’70s Show with Grace’s husband, Topher Grace.

The internet lit up with articles and comments about the post, with fans wondering whether it was a coded message to Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher, two other That ’70s Show alumni who wrote a letter to the judge defending Masterson. “Topher Grace’s wife breaks silence after That ’70s Show stars support Danny Masterson,” one headline read.

What online commentators did not know—what Grace has not shared publicly, until now—is that the post was much more personal. A lawsuit she filed in November in New York Supreme Court alleges that 16 years ago Grace was raped by a high-profile fashion photographer who lured her into his apartment with promises of stardom. The encounter changed the course of her life, she says, driving her out of New York, out of the modeling industry, and eventually out of entertainment altogether.

Three other women have already anonymously accused the photographer, Seth Sabal, of sexual harassment—allegations he forcefully denied. But Grace lived in fear of speaking up: for her career, for safety, for what her friends and family would think.

Only now, at 35, after starting over as a social worker and raising a family, does she feel ready to come forward with her story.

“Everything I was afraid of does not hold the weight it did when I was [younger],” she told The Daily Beast in an exclusive interview. “He no longer holds any power over me.”

Topher and Ashley Grace attend the 2019 Vanity Fair Oscar Party

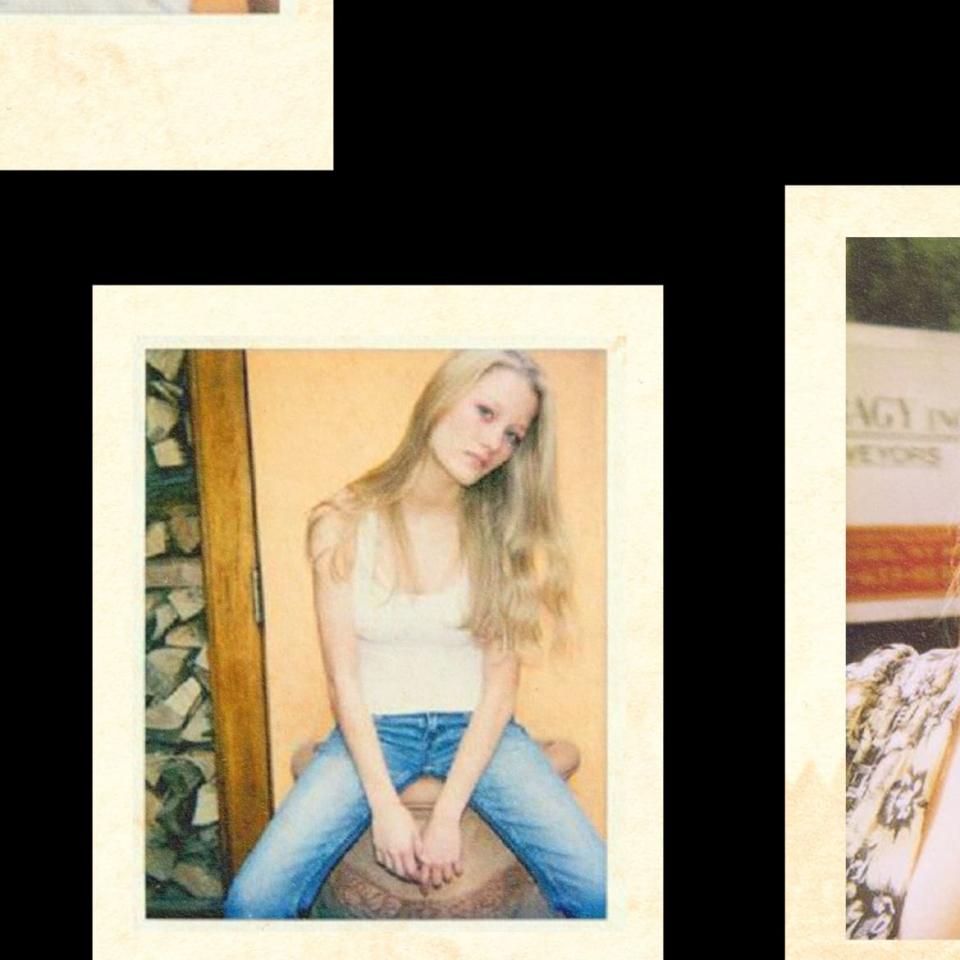

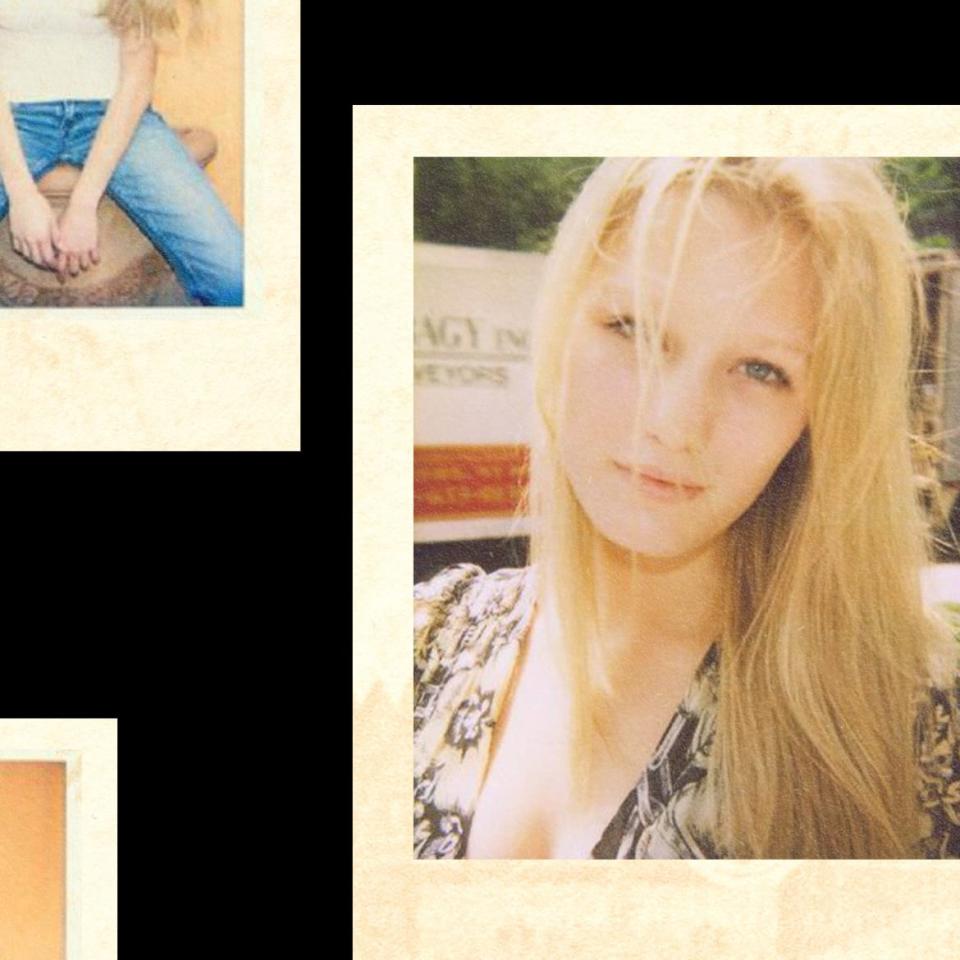

Grace grew up in Indiana, a church-going teen pageant queen and high school theater star. As a teenager, someone suggested she try modeling, and she signed with a small agency in Chicago. That led to shoots with Abercrombie and Fitch, which led to a modeling competition, which led to her signing with a major modeling agency, which led to her moving—at age 17, entirely alone—to New York City.

Grace’s life in the big city was more exciting than she could have anticipated, but also less glamorous: She lived in a crowded “model apartment” owned by her agency, then in a tiny one-bedroom in Bushwick where she subsisted largely on boxed mac and cheese. She worked at the whim of her agency, taking whatever shoots they booked in hopes of catching her big break.

One of those shoots was with Seth Sabal, a high-fashion photographer who has shot for brands including Calvin Klein, Donna Karan, and Victoria’s Secret. It was a “test shoot,” meaning she would not get paid, but Grace was thrilled at the chance to work with such a big name.

But as soon as she got to Sabal’s studio, things felt off. Grace was 18, still attending church regularly and rarely drinking. In her suit, she says Sabal pressured her to down vodka cranberries and pose without underwear. She felt uncomfortable, but when he asked her agency if they could shoot again—for a major magazine, and for a fee—she felt she couldn’t say no.

At the second shoot in August 2008, Grace says, Sabal asked her to work with him again, but without the involvement of her agency. She says she pushed back but he insisted, claiming it was “a hassle to go through her agents [and] that he did not have time,” according to the lawsuit. Eager for more exposure and hurting for money, she acquiesced.

About a week later, Grace, then 19, returned to Sabal’s Tribeca studio, which doubled as his apartment. The suit alleges that the shoot began like the others, with Sabal, then 30, pushing liquor on her as she sat through hair and makeup. Grace says she felt somewhat calmed by the presence of Sabal’s then-girlfriend, model Yuliana Bondar, but alleges that she became concerned when the hair and makeup team left and Bondar appeared in the living room with her “outfit” for the shoot: a single pair of nylons with nothing underneath.

Bondar flitted in and out of the room as Sabal began to pose Grace in increasingly suggestive ways, the suit claims. She begged Bondar to stay in the living room with them but was brushed off, with Bondar telling her the photographs Sabal was taking would “change [her] career because they were going to be so good,” the suit claims.

After 15 or 20 minutes, Sabal suggested a change of scenery. He led her into a bedroom, pressured her to snort cocaine and get on the bed, then turned on a video camera and aimed it at her, despite her protestations. Drunk, high, and paralyzed with fear, Grace followed Sabal’s commands to pose for the camera, even as he climbed on top of her and raped her, the suit claims.

“I think I made the decision that I thought was safest for me in that moment,” Grace told The Daily Beast. “Which was to go [internally] somewhere else.”

Leaving the apartment afterward, Grace says, she stopped to think about how hideous the building’s door looked. (“I think I remember that because I was so happy to be outside,” she says.) Then she walked home, sat on the floor of the shower, and cried.

To this day, she says, one of her biggest regrets is not telling anyone what had happened.

“If I could wave a wand, I would walk out of the apartment, I’d walk into the next bodega and ask to call the police,” she said. “That is what I wish I could get that back: the opportunity to ensure that he could not do that to somebody else.”

Grace spoke to The Daily Beast this week from her “office” on the top floor of her California home, which was littered with her three kids’ toys and, in the corner, an unused Peloton. “When I started getting my master’s program, I had these dreams of this being an adult space,” she said with a laugh. “That lasted about three weeks.”

Now a social worker and adjunct professor at Cal State University in Northridge, she speaks with the confidence of an academic versed in the language of trauma. She refers to what happened to her as a backpack full of rocks—one she can never take off, but which she can remove the weight from, stone by stone.

But it took years for Grace to get to a place where she could discuss her experience with anyone, much less a reporter. After the assault, she spent a “dark” few years in New York before moving to Los Angeles to pursue acting and a fresh start. She landed roles on Workaholics, True Blood, and True Detective, and met her husband at an event for a charity that sent actors to children’s hospitals. But the industry felt too similar to modeling, she says, and she lived with the fear that “every situation I was in could turn it into what happened to me that night.”

It was Topher who suggested she try therapy, after she told him about Sabal and other past traumas. The experience affected her so greatly that she decided to go back to school, age 26, enrolling in college for the first time to study social work.

“Once I realized that somebody could be in this much pain and something might actually be able to help, it was the only meaningful thing I could think of doing with my life,” she said.

Still, she occasionally found herself Googling Sabal to see if anyone had reported similar behavior. In 2018, as the Me Too movement reached its zenith, she stumbled on a Boston Globe story about sexual misconduct by fashion photographers that included claims against Sabal. Three models interviewed by the paper’s vaunted Spotlight team accused him of sexual harassment, including one who claimed Sabal plied her with alcohol and asked to take off her underwear when she was just 17.

Sabal denied these claims in a statement from his lawyer at the time, saying he had “never sexually harassed anyone and never forced anyone to do something they weren’t comfortable with.” His lawyer took care to add that he had not lost any work as a result of the allegations, saying he was semi-retired but still taking on “special projects,” and that “people from different points in his career” had reached out to offer their support.

“He would never do any of the things that were hinted at and the allegations that were made were somewhat obtuse. Some anonymous model making sort of vague allegations,” his lawyer at the time, Carlos Carvajal, told Women’s Wear Daily. “Seth is very comfortable with his reputation that he built over 30 years.”

Sabal and Carvajal did not respond to multiple requests for comment for this story.

Grace said she had hoped up until this point that she had been an outlier; that there was something unique about her that caused Sabal to target her. When she read the Boston Globe article, she realized she was wrong. She reached out to the reporters on the story, telling them she had an allegation that went even further than what they had printed and asking if they were planning a follow-up. They were not.

“For a second, [I thought] maybe I was going to be brave enough to say something,” she said. “And then the opportunity wasn’t there, and so I just clammed back up again.”

Until, that is, six months ago, when she posted what she thought would be a largely unremarkable Instagram story. She wouldn’t comment specifically on Masterson, but said of the post: “I feel compelled to speak up when survivors are not centered in the story of their own trauma.”

“I saw victims that were seeking justice—and had won justice—and that’s really where the conversation should be: the bravery that it takes and the strength that it takes to get to that point,” she added later. “We don’t need the cacophony of nonsense that continues to follow the perpetrator at that point. Just no.”

It wasn’t long after the Instagram post that Grace was struck with the inspiration to file her suit. Cal State had recently asked her to teach a class on child abuse and neglect, with a section on child sexual abuse. When she started the sexual abuse unit, she said, her office hours became a “revolving door” of students coming to talk to her about their own sexual assaults—some of them as children, but many of them as young adults.

Grace says she offered counseling and support, but whenever she informed the students of their legal rights, they insisted they did not want to pursue them. She was frustrated but sympathetic; after all, she had not reported Sabal for many of the reasons her students were offering now.

She was driving home from work one evening, after staying late to talk to yet another student survivor, when it struck her that none of those reasons applied to her anymore. She had a supportive partner, a loving family, and was far away from the industry that had made her feel too powerless and vulnerable to speak out.

“A light bulb clicked,” she said. “I couldn’t believe that I hadn’t realized until that moment that this person holds no power over me anymore.”

Grace knew that New York had recently passed a law called the Adult Survivors Act, which gave survivors a one-year “lookback window” to file lawsuits over assaults that occurred outside the statute of limitations. But the window closed in mid-November, and she was running out of time.

Determined not to miss her chance to speak out again, Grace reached out to four different law firms about filing a case under the act. To her surprise, the attorneys told her she had a strong case. None were willing to represent her on a contingency basis, however, because she was not filing suit against a notably wealthy person or a corporation.

So Grace decided she would finance the suit on her own. Working with attorneys from McAllister Olivarius, she drafted a complaint accusing Sabal of assault and sexual battery, and Bondar of negligence. They filed on Nov. 22—one day before the Adult Survivors Act window closed.

Sabal has not responded to the suit, and Grace’s lawyers have been unable to serve him. (In a motion filed this week, her legal team detailed the lengths they went to to track him down, including hiring a private investigator.) He no longer lives in New York; a glowing profile in a local newspaper published in 2015 says he returned to his hometown in Arizona to teach photography at a community college. The school, Cochise College, told The Daily Beast he had not worked there since May 2016.

Grace doesn’t know whether she’ll ever get to see Sabal in court, much less get the judgment she desires. She has had to separate her feelings around the case from her desire from any specific outcome; her happiness from the agreement of a judge or jury.

She simply wants the chance to take a stand, she said; to do what she did not feel strong enough to do at 19, or 25, or even 30.

“I want to be able to look at my kids and to say, ‘You don’t have the right to do this to other people. Other people don’t have the right to do this to you,’” she said. “And have them be able to see that when someone did it to their mom, she lived that value out: She held somebody accountable.”

“To me, it’s more about standing behind what I so deeply believe, which is that you don’t get to do this to other people,” she added. “And if I didn't file this lawsuit, I would’ve lost my only opportunity potentially to be able to say, ‘You don’t get to do this to me.’”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo News

Yahoo News