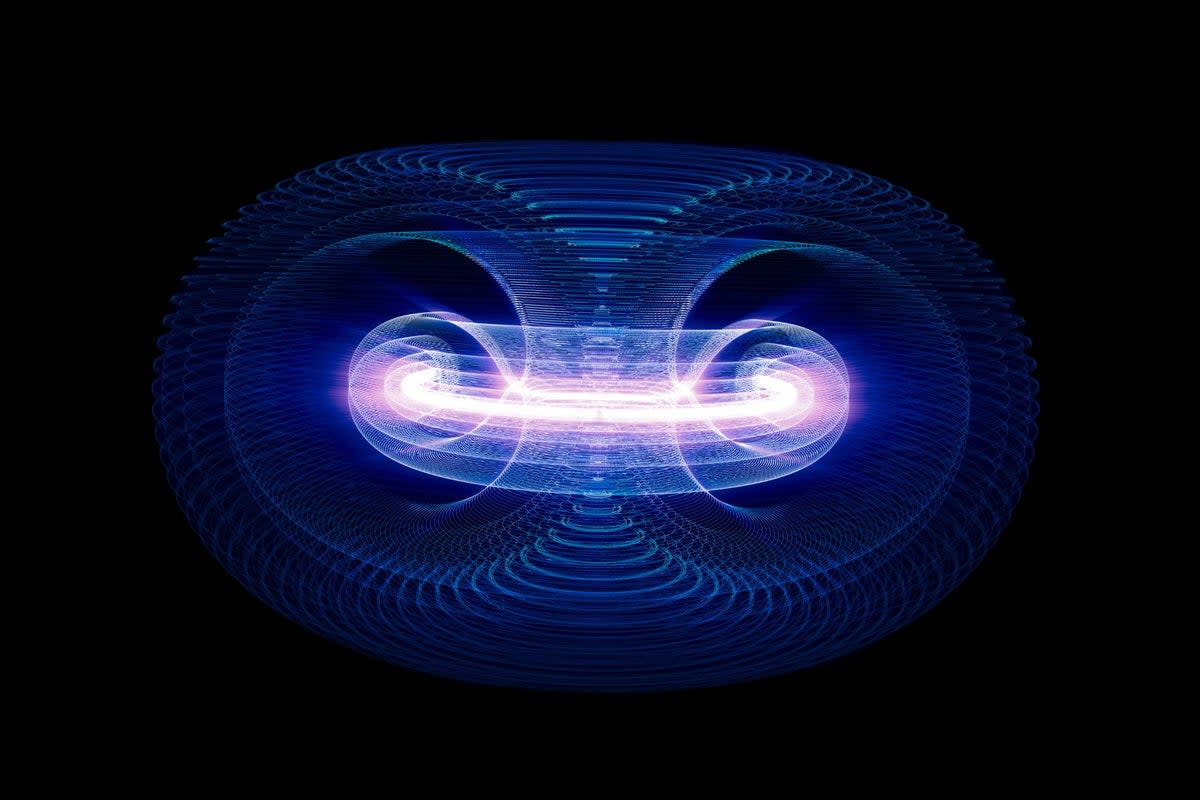

AI solves nuclear fusion puzzle for near-limitless clean energy

Scientists have used artificial intelligence to overcome a huge challenge for producing near-limitless clean energy with nuclear fusion.

A team from Princeton University in the US figured out a way to use an AI model to predict and prevent instabilities with plasma during fusion reactions.

Nuclear fusion has been hailed as the “holy grail” of clean energy for its potential to produce vast amounts of energy without requiring any fossil fuels or leaving behind any hazardous waste.

The process mimics the same natural reactions that occur within the Sun, however harnessing nuclear fusion energy has proved immensely difficult.

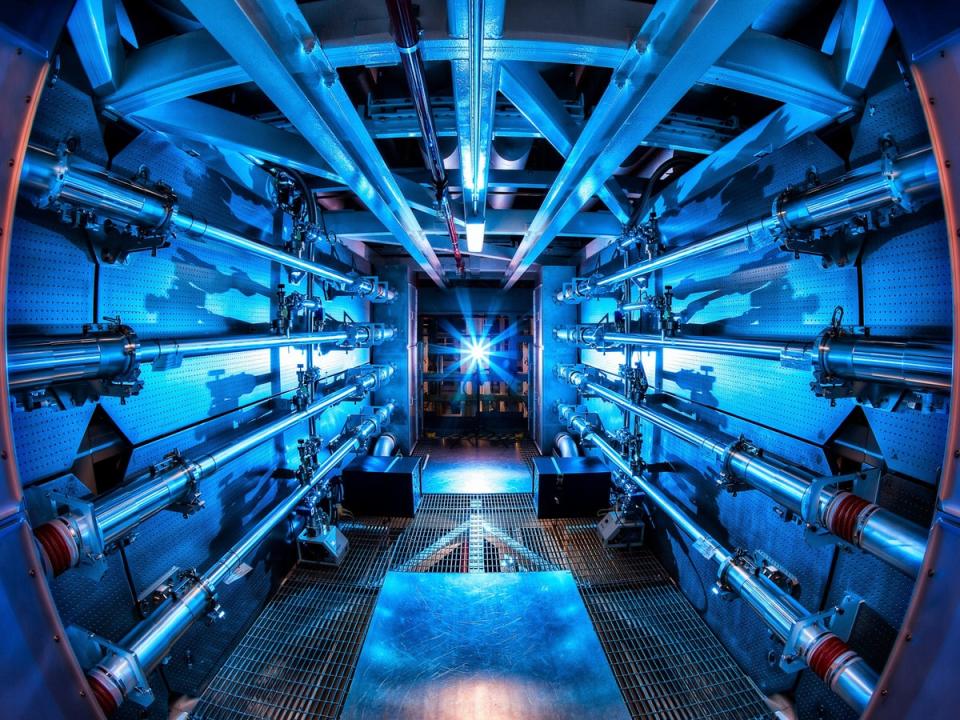

In 2022, a team from the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California achieved the first ever net energy gain with nuclear fusion, meaning they were able to produce more energy than was input for the reaction.

It was only a small amount – roughly enough to boil a kettle – but it represented a major milestone towards achieving it at scale.

The latest success means another significant obstacle has been passed, with the AI capable of recognising plasma instabilities 300 milliseconds before they happen – enough time to make modifications to keep the plasma under control.

The new understanding could lead to grid-scale adoption of nuclear fusion energy, according to the researchers.

“By learning from past experiments, rather than incorporating information from physics-based models, the AI could develop a final control policy that supported a stable, high-powered plasma regime in real time, at a real reactor,” said research leader Egemen Kolemen, who works as a physicist at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory where the breakthrough was made.

The latest research was published in the scientific journal Nature on Wednesday in a paper titled ‘Avoiding fusion plasma tearing instability with deep reinforcement learning’.

“Being able to predict instabilities ahead of time can make it easier to run these reactions than current approaches, which are more passive,” said SanKyeun Kim, who co-authored the study.

“We no longer have to wait for the instabilities to occur and then take quick corrective action before the plasma becomes disrupted.”

Yahoo News

Yahoo News